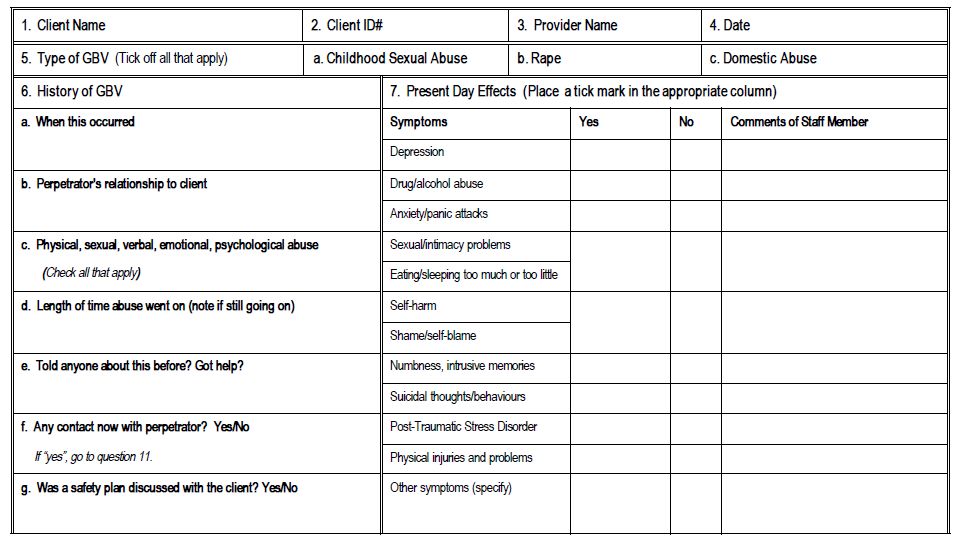

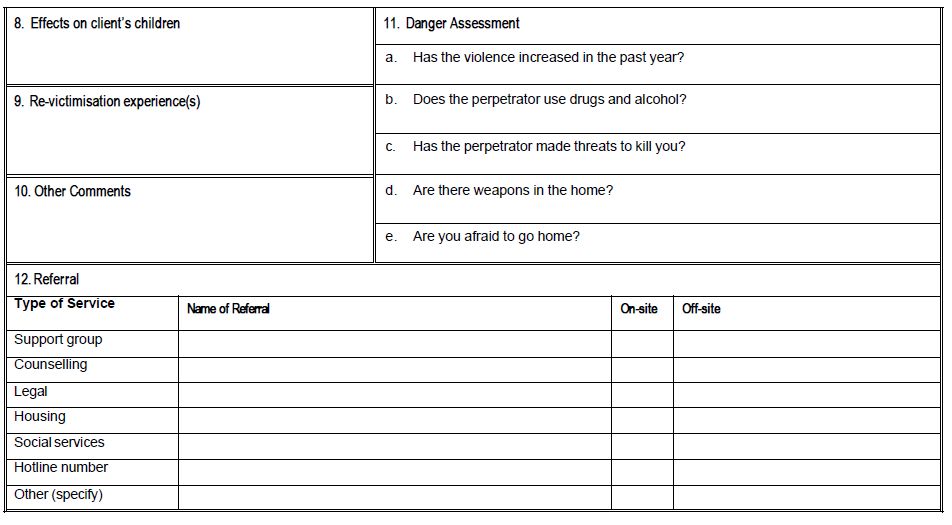

- A health information system is needed to gather data for overseeing client care as well as for monitoring services. Each health facility providing services should keep statistics using a standardized data collection form.

- Client registration formats at a minimum, should collect information on:

- The type of violence experienced

- The sex of the person

- The age of the survivor

- The age and relationship of the perpetrator to the survivor (Velzeboer, 2003)

- Additional demographic information may be collected on whether the incident was rural/urban, and by population sub-group (e.g. indigenous; ethnic and racial categories; migrant; women with disabilities; other prominent or especially excluded groups).

- The case record should also include a careful description of the violence, including the type of assault, the number of aggressors and time of aggression. The write-up should as much as possible use the woman’s own words and should avoid any language that is judgemental or critical of the survivor’s observed behaviour or appearance that may be used against the women in any subsequent legal proceedings (Tavara, 2006).

- It is critical to guarantee complete confidentiality, not only on the files themselves (e.g. by using a patient number instead of the patient’s name), but also by ensuring that all records are kept in locked files. Only select staff should have access to the keys for the files and management should develop a system for file distribution and sharing within the facility.

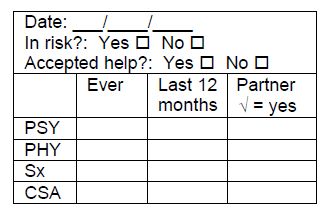

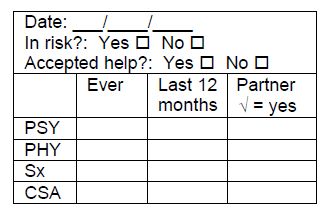

- IPPF/WHR has developed the following stamp to include on intake forms to indicate that a client has been screened for violence:

Source: excerpted International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region, 2000. “Tools for Service Providers Working With Victims of Gender-Based Violence.” Available in English.

Example: In Malaysia, colour coding or stamping on registration files were two systems developed to protect clients’ confidentiality (Rastam, 2002; Rogow, 2006; and Guezmes & Vargas, 2003, cited in Colombini, 2008).

Balancing Confidentiality with the Need for Complete Medical Records International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region

One important challenge for many clinics is ensuring that providers are able to record detailed information about women’s experiences of violence without revealing this information to a third party without the woman’s consent. Participants in the IPPF/WHR initiative felt that abuse and violence have a major impact on women’s sexual and reproductive health and are therefore an essential part of a woman’s medical history that is necessary for ensuring appropriate care. On the other hand, some providers felt that they did not always want other staff members in the organization to know about the violence that their clients revealed. In fact, during the IPPF/WHR baseline study, some physicians said that they wrote down all information about violence on the clinical history form in code so that they could access this information during future consultations, but none of their colleagues in the clinic would know what the information meant. This appeared to be a particular challenge in larger clinics where women did not have their own personal health care provider but saw different providers depending on who happened to be available that day. In general terms, all three member associations decided that providers should write women’s answers to gender-based violence screening questions on the clinical history forms in a manner that was clearly legible to other providers.

To protect women, the clinics strengthened the policies safeguarding the way that clinic records were stored and asked providers to make it clear to women who disclosed violence how the information would be recorded and used. Raising providers’ awareness of violence as a health issue made it easier to convince them that this information should be part of a woman’s medical record. Moreover, it was helpful to point out that medical records in their clinics contained all kinds of sensitive and confidential information, including contraceptive use, pregnancy status, and the results of exams for sexually transmitted infections. A breach of confidentiality regarding any of these sensitive matters can put a woman at risk. A history of violence or abuse should not be seen as shameful information to record (a concern of some providers). Clinics have an ethical responsibility to protect the confidentiality of all medical records to a point where recording details of violence should not put women in danger. Nonetheless, the three IPPF member associations are still struggling to resolve a number of issues. For example, most have not developed systems to share information about violence between professionals from different services (such as counselling and medical services). For example, if a woman discloses a history of violence to a family planning counsellor during an intake procedure, how much of that information should be available to the physician who would attend to her sexual and reproductive health needs? In the member association clinics, information about a history of violence disclosed in counselling, medical and psychological services often remains in separate registries. During the follow-up evaluation of the IPPF/WHR initiative, the consultant recommended that when health programs maintain separate registries, they should consider recording a summary of other services received in the medical history form, just as physicians do when they refer clients to specialists in the medical field, unless women do not want this information recorded. However, some evidence suggests that service providers—rather than female clients—are the ones most resistant to sharing information among medical, legal and psychological services.

Source: excerpted from Bott, S., Guedes, A., Guezmes, A. and Claramunt, C., 2004. Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Professionals in Developing Countries. New York: IPPF/WHR, pg. 57. Available in

English and Spanish.

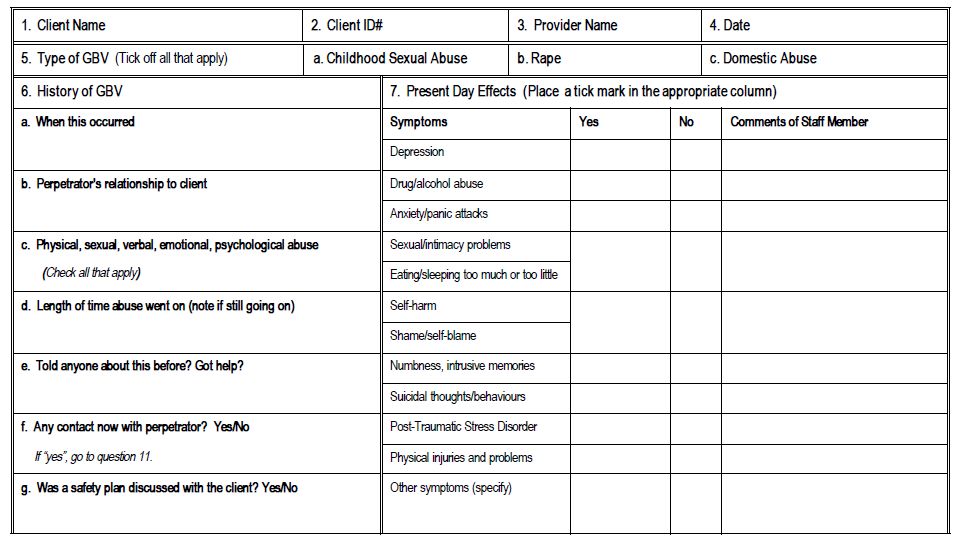

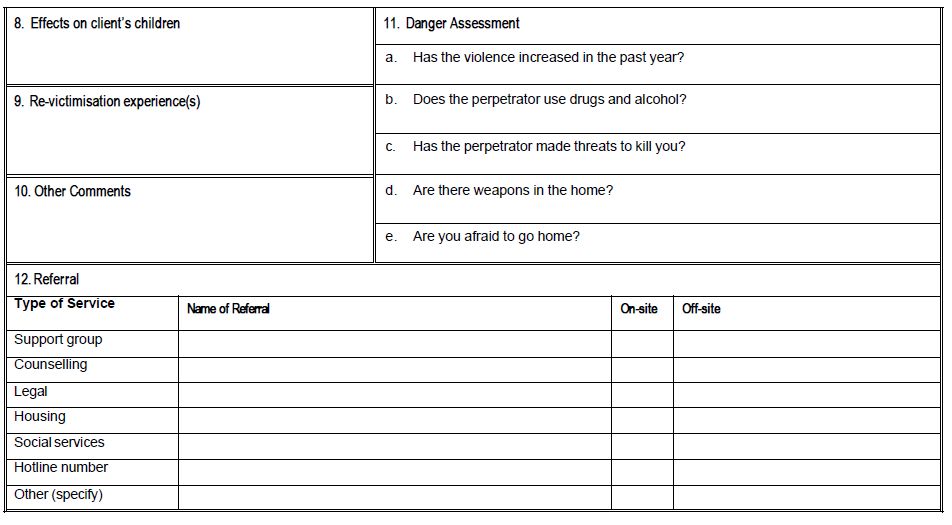

Source: excerpted from Billings/UNFPA. 2001.

A Practical Approach to Gender-based Violence: A Programme Guide for Heath Care Providers and Managers, Appendix 9. Available in

English,

French and

Spanish.

Illustrative Tools:

A Practical Approach to Gender-based Violence: A Programme Guide for Heath Care Providers and Managers (Billings/UNFPA, 2001). Includes guidance on data collection. Available in English, French and Spanish.

The Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Data Resource Center has numerous examples of incident report forms and case management forms from the majority of states in the United States. Sample forms are available in English.

Gender-based Violence Information Management System Project Tools. The GBVIMS is a multi-faceted initiative being undertaken in humanitarian settings to enable humanitarian actors to safely collect, store, and analyze reported GBV incident data. The GBVIMS includes: a workbook that outlines the critical steps agencies and inter-agency GBV coordination bodies must take in order to implement the system; an Excel database (the “Incident Recorder”) for data compilation and trends analysis; and a global team of GBV and database experts from UNFPA, UNHCR and the International Rescue Committee for on-site and remote technical support. For more information about the tools, e-mail gbvims@gmail.com