- Screening is “asking women about experiences of violence/abuse, whether or not they have any signs or symptoms.” (Bott et al., 2004) Without screening, health services mainly respond when survivors take the initiative to disclose.

- When done appropriately, screening creates a record of the main violence issues for the survivor, which in turn determines what care and support she needs from the provider doing the screening, and from others in the facility or the community. Routine screening increases the likelihood that providers can ensure appropriate care for survivors.

- Without routine screening, providers typically identify only a fraction of women requiring assistance with physical or sexual abuse. Routine screening for violence has increasingly been considered the standard of care within women’s health services in the United States and other industrialized countries (American Medical Association, 1992; Buel, 2001).

- However, there are widespread concerns about the risks of routine screening, particularly in resource-poor settings where there is limited training to prepare providers to conduct screening (Garcia Moreno, 2002b) and/or lack of support to providers who routinely screen clients. Routine screening may harm women in settings where providers are insensitive to violence issues or are otherwise not equipped to respond appropriately, where privacy and confidentiality cannot be ensured, and where adequate referral services do not exist. Poorly implemented routine screening can put women at additional risk of violence (Bott et al., 2004).

- When considering whether to implement screening, providers should first understand the four basic approaches to screening:

- Universal screening involves asking all women about abuse at all first visits. This approach demands that the minimum requirements for safety and quality of care are met.

- Selected integration involves routine screening in specific service areas (e.g. emergency departments) or areas that can improve overall health outcomes (e.g. prenatal care, HIV and AIDS clinics, family planning, etc.) (Velzeboer, 2003). This can be a cost-effective way to identify women, but only if staff are well trained and motivated. It is also critical that any interviews with survivors be coordinated, so that the woman does not have to repeat the same story and potentially be retraumatized (Acosta, 2002).

- High risk screening involves screening groups of women who have been identified as being at high risk of violence. Depending on the setting, such groups often include girls in child marriages, domestic workers, girls in households without either parent, sex workers, women and girls in emergency settings, women with mental illness, those with disabilities and those who are HIV-positive.

- Selective screening is done only when there are signs or indications that violence may be occurring.

- Universal screening may not be feasible in most developing countries because of scarcity of resources. However, selected integration of routine screening into reproductive health, mental health and emergency services is recommended, as well as selective screening of women and girls exhibiting signs of abuse in other health services (Morrison, Ellsberg and Bott, 2007). Service providers must be trained in the health consequences of violence against women and girls and understand some of the possible health indicators of abuse.

- Regardless of which type of screening is implemented, health organizations have an ethical obligation to do no harm. They must be able to ensure basic precautions to protect women’s lives, health, and well- being before they implement routine screening. Basic precautions include:

- Protection of women’s privacy and confidentiality.

- Healthcare providers with adequate knowledge, attitudes, and skills to offer the following:

- A compassionate, non-judgmental response that clearly conveys the message that violence is never deserved and women have the right to live free of violence.

- Appropriate medical care for injuries and health consequences, including STI and HIV prophylaxis and emergency contraception post-rape.

- Information about legal rights, and any legal or social service resources in the community.

- Assessment of when women might be in danger and provision of safety planning for women in danger.

- Safe and reliable referrals to services not available in the facility.

- In addition, health facilities that offer screening should have a written screening protocol, a method for documenting information collected during the screening, and a monitoring and evaluation system to assess the uptake in services and quality of care related to screening.

- When designing and using a screening protocol, health care providers should take into account barriers to disclosure among women and their community, such as the taboo of speaking about violence, feelings of shame and/or guilt, concerns about confidentiality, etc. Questions in the protocol should be adapted accordingly and tested for appropriateness. A study in the Dominican Republic showed that a general initial question about how things are going with the woman’s partner worked well. A qualitative study in Kenya cited the “blurred boundaries between forced and consensual sex” as demanding more exact phrasing of questions that would elicit responses (Kilonzo et al., 2008).

Example: Consistent Screening in Venezuela Increased Identification of Women who Experienced Abuse

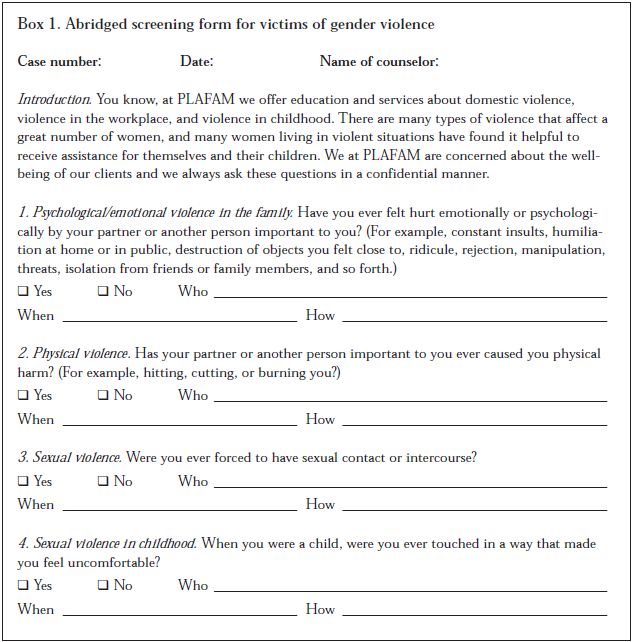

A study conducted in Venezuela found that the screening tool below, when used systematically with each client, identified that 38% of new clients were victims of violence as compared to only 7 % when counsellors relied on unsystematic screening. This study was conducted by International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region (IPPF/WHR) in collaboration with their Venezuelan affiliate, Asociation Civil de Planification Familiar (PLAFAM).

Source: excerpted from Guedes et al., 2002b. “Addressing Gender Violence in a Reproductive and Sexual Health Program in Venezuela.” in Responding to Cairo: Case Studies of Changing Practice in Reproductive Health and Family Planning, p. 266)

Additional Examples of Screening Tools:

Living Up to Their Name: Profamilia Takes on Gender-based Violence (Goldberg/Population Council, 2006). See page13. Available in English.

Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Professionals (Bott, S., Guedes, A., Guezmes, A. and Claramunt, C./International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region, 2004). See pages 109-143. Available in English and Spanish.

Screening for Domestic Violence: A Policy and Management Framework for the Health Sector (Martin, L. and Jacobs, T. 2003). See page 14. Available in English.

Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Victimization Assessment Instruments for Use in Healthcare Settings (Basile, Hertz, Back/Centres for Disease Control, 2007). This resources provides practitioners and clinicians with a current inventory of assessment tools for determining intimate partner violence (IPV) and/or sexual violence (SV) victimization. The guide was reviewed and finalized with contributions from IPV and SV experts and rape and education programme coordinators from the United States, and is presented in two sections on IPV tools and SV tools respectively. Each section provides a table listing the relevant tools, background information on its development, components, application and follow-up, psychometric properties and includes the actual assessment tool. Available in English (with 2 tools in Spanish).

Screen to End Abuse includes five clinical vignettes (Family Violence Prevention Fund). This video demonstrates techniques for screening and responding to domestic violence in primary care settings. The film is 32 minutes and is available on VHS, CD and looped (for continuous play). Available in English.

Illustrative resources:

Responding to Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence against Women: WHO Clinical and Policy Guidelines (World Health Organization, 2013). Available in English (pages 17-19).

Barriers in Screening Women for Domestic Violence: A Survey of Social Workers, Family Practitioners, and Obstetrician-Gynecologists (Tower, L. 2006). Available in English.

Model Protocol on Screening Practices for Domestic Violence Victims with Disabilities (Hoog, C. 2003). Available in English.

Improving Screening of Women for Violence: Basic Guidelines for Healthcare Providers (Stevens, 2005). Available in English.