- A fundamental role for health providers is to assess the safety of a survivor and help her stay out of danger. Some key areas of danger for those experiencing violence may include:

- Imminent harm in the next minutes, hours or days

- Short and long-term risk of being killed

- Risk of self-inflicted harm, including suicidal thoughts and impulses

- Severe sexual and reproductive health consequences, such as unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, etc.

- Danger to children who may be involved.

- Sample danger assessment questions are listed below. However, it is very important that providers design their safety assessment questions according to their cultural context, and field-test them for appropriateness and usability. It is also important that providers listen to patients when determining level of risk. Women’s assessment of their own risk is just as important, if not more, than outcomes of a risk assessment tool in predicting future exposure to violence.

- After assessing each woman’s level of danger providers can work with survivors to establish safety plans. There are different methods in attending to safety, with some settings prioritizing the survivor’s control over implementing safety plans and others promoting more pro-active follow up to ensure continuity of care, safety and access to support during a period where safety may be threatened (Council of Europe; 2008a). In all cases, the health care provider should respect the survivor’s ability to identify her own safety risks as well as possible strategies for mitigating those risks. Where danger to children involved, the health care provider should follow facility and national protocols on their protection.

Sample Danger Assessment Questions for Intimate Partner Violence

1. Has the physical violence increased in frequency over the past year?

2. Has the physical violence increased in severity over the past year?

3. Does he ever try to choke you?

4. Is there a gun in the house?

5. Has he ever forced you to have sex when you did not wish to do so?

6. Does he use drugs? By drugs, I mean “uppers” or amphetamines, speed, angel dust, cocaine, “crack”, street drugs or mixtures.

7. Does he threaten to kill you and/or do you believe he is capable of killing you?

8. Is he drunk every day or almost every day? (In terms of quantity of alcohol.)

9. Does he control most or all of your daily activities? For instance, does he tell you who you can be friends with, how much money you can take with you shopping, or when you can take the car?

10. Have you ever been beaten by him while you were pregnant?

11. (If you have never been pregnant by him, check here ____)

12. Is he violently and constantly jealous of you? (For instance, does he say

“If I can’t have you, no one can.”)

13. Have you ever threatened or tried to commit suicide?

14. Has he ever threatened or tried to commit suicide?

15. Is he violent toward your children?

16. Is he violent outside of the home?

Excerpted from Bott, S., Guedes, A., Guezmes, A. and Claramunt, C., 2004. Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Professionals. NY, NY: International Planned Parenthood Federation: Western Hemisphere Region. pg. 92, and adapted from Campbell, 1998.

- Some key issues and strategies that providers and survivors may wish to think through when developing a safety plan include:

- Possible escape routes and a place where the woman could go in case of emergency (e.g. the home of a family member or friend, ideally at an address not known to the perpetrator) if she needs to leave her home at some point in the future.

- Know/memorize phone number(s) for organizations that provide help, if any exist in the area.

- Know where to get emergency contraception and post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent STIs, including HIV in the case of sexual violence.

- Notify one or more trusted neighbours to watch for signs of violence and to call the police or other community members if they notice anything unusual.

- Talk to children about what to do and where to go for help in the case of a violent incident and rehearse an escape plan with them.

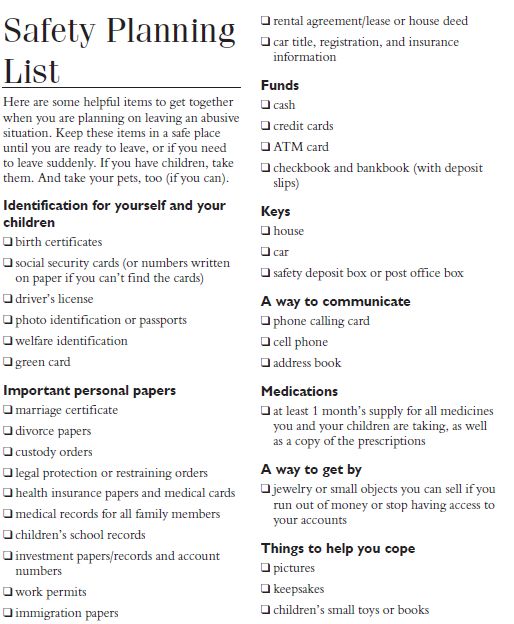

- Decide what a woman needs to have ready if she needs to leave her home in a hurry (e.g. clothes, money, documents, keys).

- Pack a bag with these items and store it somewhere in her home or with a friend or relative.

- Come up with strategies for reducing risk once a conflict begins. For example, if an argument cannot be avoided, try to have it in a room with an easy exit.

- Stay away from rooms where weapons are available. (Adapted from Bott et al., 2004, and Velzeboer et al., 2003)

- It may be useful to have a checklist on hand to review some of these safety issues with those at risk:

Source: National Women’s Health Information Center. 2008. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women’s Health. Available in pdf.

- If women are in immediate danger and cannot return home, it will be important to find them safe haven. It may be useful to create safe spaces within health services where women can stay until they can be referred to a shelter/safe space.

Illustrative Tools:

For additional resources on safety planning, search the tools database.

Violence Against Women Safety Planning List. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women’s Health (National Women’s Health Center, 2008). Available in English.

Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Victimization Assessment Instruments for Use in Healthcare Settings (Centres for Disease Control, 2007) This resource, by KC. Basile, MF Hertz, and SE Back for the Centres for Disease Control, provides practitioners and clinicians with a current inventory of assessment tools for determining intimate partner violence (IPV) and/or sexual violence (SV) victimization. The guide was reviewed and finalized with contributions from IPV and SV experts and rape and education programme coordinators from the United States, and is presented in two sections on IPV tools and SV tools respectively. Each section provides a table listing the relevant tools, background information on its development, components, application and follow-up, psychometric properties and includes the actual assessment tool. Available in English (with 2 tools in Spanish).

Safety Plan (North Carolina Coalition against Domestic Violence). Available in English. This form is a template for domestic violence survivors and those working with them. The safety plan provides a sample framework for survivors to identify short and long-term steps to leave an abusive situation. Based on the context in the United States, the plan includes sections addressing physical safety, financial security, and the well-being of children of violence survivors, and may be modified as relevant for other settings.

Model Protocol On Safety Planning for Domestic Violence Victims with Disabilities (Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2003). Available in English.

Inventory of Spousal Violence Risk Assessment Tools Used in Canada, Department of Justice. Available in English for purchase.

- Aid to Safety Assessment Planning (ASAP) The Aid to Safety Assessment Planning is a manual that was created as a result of a partnership between the Victim Services and Crime Prevention Division, BC Ministry of Public Safety and the BC Institute Against Family Violence. The objective of this manual is to reduce the risk of violence by providing a comprehensive and coordinated safety management strategy that victim service workers can use in cooperation with other relevant justice agencies to support women in making safety assessment decisions. It was designed to examine the risk factors from the victim’s perspective and emphasizes the need for relevant agencies and the victim to work together and, where appropriate, share information on known risk factors. The manual and sample worksheet incorporates items from established tools such as the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment (SARA) and the Brief Spousal Assault Form for Evaluation of Risk (B-SAFER) to create appropriate safety plans. To order a copy of the ASAP manual, please visit the Centre for Counselling and Community Safety, Justice Institute of British Columbia website.

- Brief Spousal Assault Form for the Evaluation of Risk (B-SAFER) The Brief Spousal Assault Form for the Evaluation of Risk (B-SAFER) was developed collaboratively by the British Columbia Institute Against Family Violence, P. Randall Kropp, Ph.D., Stephen D. Hart, Ph.D., Henrik Belfrage, Ph.D. and the Department of Justice Canada. The development of the B-SAFER tool was based on a number of objectives: to facilitate the work of criminal justice professionals in assessing risk in spousal violence cases, guide the professionals to obtain relevant information necessary to assess level of risk, assist victims in safety planning and ultimately work to prevent future harm and more critical incidents.

- Danger Assessment The Danger Assessment is used by Victim Services in New Brunswick. In Nova Scotia, staff of transition houses, Victim Services and Child Welfare Services (under Department of Community Services) are trained to use the Danger Assessment tool, developed by Jacquelyn Campbell, Ph.D., R.N., F.A.A.N. from the United States. The use of this tool is part of the collaborative process through the High Risk for Lethality Case Coordination Protocol Framework. Information sharing is initiated with relevant agencies if any of the primary service providers designate a woman’s file as high risk. The Danger Assessment tool is comprised of two parts: the first portion of the tool evaluates severity and frequency of abuse by providing the woman with a calendar of the previous year. The woman is asked to mark dates of past abuse on a calendar. Incidents are ranked from least to most severe. Indicators include: slapping, pushing, punching, kicking, bruises, “beating up” (i.e. burns, broken bones and miscarriage), threat to use a weapon and finally, use of a weapon with wounds. The second portion of the tool is a 20-item instrument which includes a weighted scoring system to count yes/no responses of risk factors linked with intimate partner homicide. For more information, please see the website.