- Counseling is a critical intervention that can have positive benefit for survivors—including higher physical functioning, lower levels of depression (Tiwari, 2005 cited in Ellsberg, 2006), higher self-esteem and assertiveness, and even decreased exposure to abuse (Laverde, 1987, cited in Ramsey , 2005).

- Providers should be trained to ask women directly about violence. In particular, women in antenatal/prenatal care and women showing certain conditions, such as injuries, anxiety symptoms, substance abuse, depression, sexually transmitted infections or gynaecological symptoms.

- Cognitive-behavioural therapy may be especially useful in reducing mental health problems associated with both intimate partner violence and sexual violence (WHO, 2010a). However, it is critical that those providing emotional care and support have adequate counselor training in issues related to the psychological impact of different types of violence against women and girls (Bott et al., 2004). Some interventions, including those for post-traumatic stress disorder require a psychologist or highly trained mental health specialist. Others, such as crisis-intervention have been shown not to be effective.

- Specialist experience and skills in violence against women should include, at minimum, knowledge about the following (also see counseling skills resources in staff training):

- A gendered analysis of violence against women

- Crisis intervention techniques

- Trauma, coping and survival

- Current understandings of well-being and social inclusion

- ConfidentialityCommunication skills and intervention techniques

- An overview of criminal and civil justice systems

- An update and review of relevant laws

- The availability of state and community resources

- Non-discrimination and diversity

- Empowerment (Council of Europe, 2008a)

- The Council of Europe recommends that one specialist counseling service be available per 50,000 women (or at least one in every regional city) with referrals to other therapeutic services only to qualified professionals (Council of Europe, 2008a). Establishing counseling services in health facilities can not only improve accessibility for survivors, but can also have secondary benefits, such as raising the profile of the issue among health care providers.

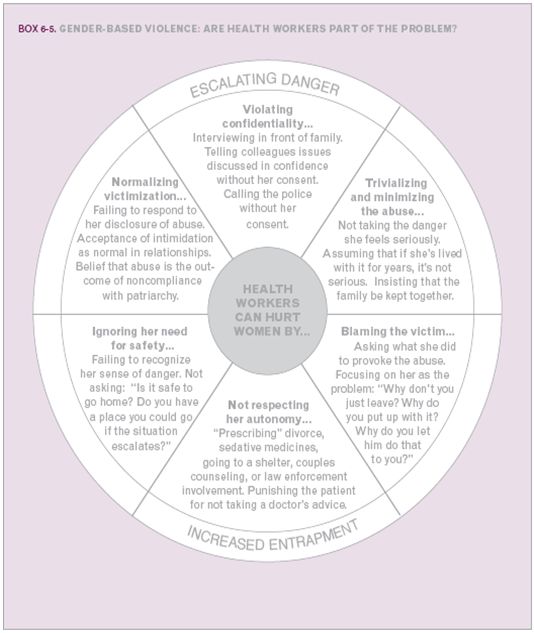

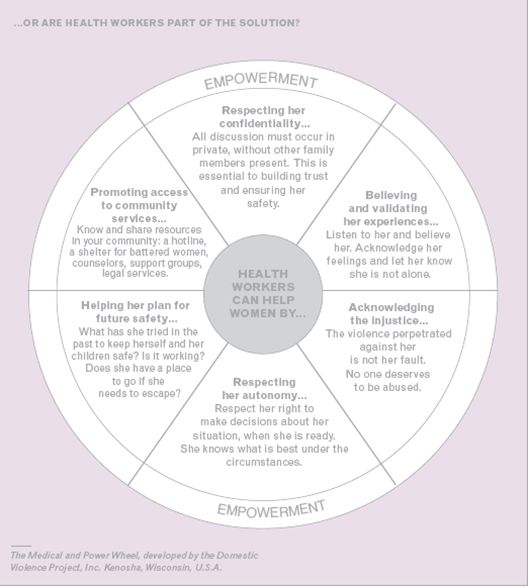

- However, in many development settings the Council of Europe standard may be unrealistic, and this standard may not address the needs of women living in hard-to-reach rural areas. It is therefore critical that all health care providers working with survivors have a thorough understanding of supportive techniques for engaging with survivors that are based on guiding principles. As the following diagrams illustrate, simply adhering to basic principles when working with survivors can have a therapeutic effect.

Source: Velzeboer, M., Ellsberg, M., Arcas, C., and Garcia-Moreno, C., 2003. Violence against Women: The Health Sector Responds. Washington, DC: PAHO, pgs.70 & 71.

- If professional counsellors are not available, if there are barriers to accessing individual psychosocial support or as a complement to existing services, support groups can be created with health personnel serving as trained facilitators (Ellsberg and Arcas, 2001).

- While facilitators do not necessarily need to have advanced degrees in psychology, social work, or a related field, they should have specific training in violence against women issues, as well as in facilitating a support group, and should understand the process for designing support groups, the stages of group development, the role of the facilitator, etc.

Case Study: Women’s Support Groups as part of an Integrated Model of Care of Family Violence in Central America (Pan American Health Organization)

Support groups can be important to the psychosocial well being of survivors, particularly in resource-poor settings, where there may be fewer mental health providers. One of the main advantages of support groups is that they enable health centres to attend many more individuals than is possible with individual psychological care.

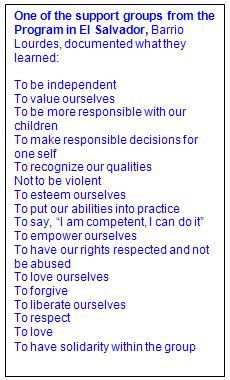

Additionally, group facilitators do not necessarily have to be mental health professionals, although special training is necessary. Another advantage is that women are given the opportunity to help each other; to realize that they are not the only ones that suffer from violence; and to develop common ties, and in some cases, collective action. These are all important elements for overcoming violence. A programme by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in Central America has tried to promote support groups through staff training and distribution of educational materials. In each one of the countries there is at least one successful pilot experience with support groups. In Central America, there are several organizations, for example, Centro Feminista de Información y Acción (CEFEMINA) in Costa Rica, with extensive experience in self-help or support groups for violence survivors. However, a review of the support groups in the region demonstrated a wide disparity in how generalized the support groups were within each country. An important realization was that the success or failure of groups had much more to do with the motivation and skill of the individual health workers than with the community characteristics, or professional training of facilitators.

One of the most comprehensive approaches was at the Polyclinic of Barrio Lourdes in El Salvador, where various support groups for survivors of violence were managed, including one for elderly women. What makes this experience noteworthy is that the groups are run by a physical therapist and special education specialist, although the center has several psychologists on staff. The facilitators were chosen not for their professional background but because of their interest in the topic and their ability to develop trust with people. For more information on lessons learned, see the document in English.

Source: excerpted from: Ellsberg, M. and Arcas, C., 2001. Review of PAHO’s Project: Towards an Integrated Model of Care for Family Violence in Central America. Final Project. Stockholm, Sweden: Department for Democracy and Social Development: SIDA evaluation, pgs. 24-25).

Illustrative Tools:

Caring for Survivors Training Manual (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2010). Module 8. Available in English.

Communication Skills in Working with Survivors of Gender-based Violence: A Five-day Training Manual (International Rescue Committee and Family Health International, 2000). Day 4. Available in English.

Counsellor’s Training Manual, Help & Shelter, Guyana (Jackson, J.). Available in English.

Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-based Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Professionals in Developing Countries (Bott, S., Guedes, A., Guezmes, A. and Claramunt, C./IPPF/WHR, 2004). See Section v.d: Women’s Support Groups. Available in English and Spanish.

Mental Health Responses for Victims of Sexual Violence and Rape in Resource-Poor Settings (Sexual Violence Research Initiative, 2011). Available in English.

THE POWER TO CHANGE: How to set up and run support groups for victims and survivors of domestic violence (NANE, AMCV, Association Artemisia, NGO Women's Shelter, and Women's Aid Federation of England, 2008). This manual produced under the Daphne Project in Europe outlines key considerations required for establishing and running support groups for survivors of domestic violence, including three possible models that can be used as a basis of running such groups. Available in English, Estonian, Hungarian, Italian, Portuguese and Serbian.

Counseling Guidelines on Domestic Violence (Southern African AIDS Training Programme, 2001) Harare, Zimbabwe. Available in English.

Trainer’s Manual for Rape Trauma Counselors in Kenya (Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya, 2006). Available in English.

Psychosocial Care for Women in Shelter Homes (UNODC, 2011). Available in English.

Several guidelines and tools have been created for humanitarian emergencies on general issues related to providing care and support that may also be useful in non-emergency contexts. These include:

- Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. These guidelines reflect the insights of practitioners from different geographic regions, disciplines and sectors, and reflect an emerging consensus on good practice among practitioners. The core idea behind them is that, in the early phase of an emergency, social supports are essential to protect and support mental health and psychosocial well-being.

- Psychological First Aid: Field Operations Guide. National Child Traumatic Stress Network and National Center for post traumatic stress disorder. An evidence-informed modular approach for assisting people in the immediate aftermath of disaster and terrorism: to reduce initial distress, and to foster short and long-term adaptive functioning. It is for use by disaster responders including first responders, incident command systems, primary and emergency health care providers, school crisis response teams, faith-based organizations, disaster relief organizations.

- Coping with disaster – A guidebook to psychosocial intervention This manual outlines a variety of psychosocial interventions aimed at helping people cope with the emotional effects of disasters. It is intended for use by mental health workers (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other counselors), by primary medical care workers (doctors, nurses, and other community health providers), by disaster relief workers, by teachers, religious leaders, and community leaders, and by governmental and organizational officials concerned with responses to disasters. It is intended as a field guide or as the basis for brief or extended training programmes in how to respond to the psychosocial effects of disasters.