- Legislation should state that police and other law enforcement officials are obligated to pursue all cases of domestic violence, regardless of the level or form of violence. (See: Report of the Intergovernmental Expert Group Meeting to review and update the Model Strategies and Practical Measures on the Elimination of Violence against Women in the Field of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, Bangkok, 23-25 March 2009, III 15 (b).)

- Legislation should require the police to give domestic violence calls the same priority as other calls involving violence. (See: Law of Georgia) For information on assigning priority levels to domestic violence calls, see: The St. Paul Blueprint for Safety, p. 21.

- Legislation should require the police to perform certain duties as part of the investigative process in domestic violence calls, including interviewing parties separately, recording the complaint, filing a report, and advising the complainant/survivor of her rights.

For example, the Law of Brazil mandates a police protocol which includes a provision requiring police to determine the existence of prior complaints of violence against the aggressor:

“… – command the identification of the aggressor and the addition of the aggressor’s criminal record to the judicial proceedings, indicating the existence of arrest warrant or record of other police occurrences

- Legislation should require the police to perform certain duties as part of the investigative process in domestic violence calls, including interviewing parties separately, recording the complaint, filing a report, and advising the complainant/survivor of her rights.

- Legislation should specifically prohibit the use of warnings to violent offenders as a part of the police or judicial response to domestic violence. Warnings do not promote offender accountability and they communicate a message that violence will be tolerated.

Legislation should require police officials to develop policies for implementation of domestic violence laws that provide specific directives to front-line law enforcement officers. For example, complete and accurate documentation of domestic violence incidents in police reports is an essential component for offender accountability. See The St. Paul Blueprint for Safety, p. 31.

- Legislation should require specialized police units are to be created for the investigation and prosecution of domestic violence cases. These units should include a sufficient number of female police officers so that complainants/survivors can interact with an officer of the same sex if she chooses to do so.

Examples: In 2011, Pakistan established nine female police stations in Karachi, Larkana, Hyderabad, Peshawar, Abbottabad, Islamabad, Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Faisalabad. The stations are staffed by female police officers to handle reported cases of violence against women. Alongside the development of preventive legislative and legal measures, the new stations will ensure more comprehensive measures of protection for women. For example, the female officers will provide a barrier against gender harassment by ensuring that a female officer is present during the interrogation of a woman in custody.

See "Over 11,000 cases of violence against women registered since 2009", Dawn.com (February 21, 2011).

Similarly in Sri Lanka, the Sri Lanka police department created a special branch called the Women and Childcare Bureau. The bureaus are staffed primarily with female police officers and are located in nearly every police station around the country. See Munasinghe Sandamani Prasadika, SRI LANKA: The Domestic Violence Act and the actual situation, Asian Human Rights Commission (May 17, 2012).

The Law of Zimbabwe provides that “where a complainant so desires, the statement of the nature of the domestic violence shall be taken by a police officer of the same sex as that of the complainant.” Section 5(2)(b).

See the law of Spain; and the Handbook on Effective police responses to violence against women (2010) p. 39.

- Legislation should require police to develop a safety plan for complainants/survivors. See Handbook on Effective police responses to violence against women (2010), p. 74-75.

- Legislation should provide sanctions for police who fail to implement the provisions. ee Law of Albania, Article 8(5).

The UN Model Framework provides a detailed list of police duties within the context of complainant/survivor rights (Part III A) and a list of minimum requirements for a police report (paragraph 23).

See Responding to Domestic Violence: A Handbook for the Uganda Police Force (2007).

The US Model Code recommends important provisions for the duties of a police officer, including confiscating any weapon involved, assisting the complainant in removing personal effects, and “taking the action necessary to provide for the safety of the victim and any family or household member.” See Family Violence: A Model State Code, Sec 204.

See also Vision, Innovation and Professionalism in Policing Violence Against Women and Children (2003), a Council of Europe training book for police; Handbook, Ch. 3.8.1.

CASE STUDY: The Duluth Pocket Card, a laminated pocket card which was developed by police in Duluth, Minnesota, with protocol to document domestic violence incidents:

Card 1: Duluth Police Department Report Writing Checklist

a) Domestic Assault Arrest/Incident

Document the following:

1. Time of arrival and incident

2. Relevant 911 information

3. Immediate statements of either party

4. Interview all parties and witnesses documenting:

(a) relationship of parties involved/witnesses

(b) name, address, phone - work/home, employer, etc

(c) individuals’ accounts of events

(d) when and how did violence start

(e) officer observation related to account of events

(f) injuries, including those not visible (e.g. sexual assault, strangulation)

(g) emotional state/demeanor

(h) alcohol or drug impairment

5. Evidence collected (e.g., pictures, statements, weapons)

6. Children present, involvement in incident, general welfare. Children not present, but reside at the residence

7. Where suspect has lived during past 7 years

8. Medical help offered or used, facility, medical release obtained

9. Rationale for arrest or non-arrest decisions

10. Summarize actions (e.g., arrest, non-arrest, attempts to locate, transport, referrals, victim notification, seizing firearms)

11. Existence of OFP, probation, warrants, prior convictions

12. Victim’s responses to risk questions including your observations of their responses

13. Names and phone numbers of 2 people who can always reach victim (#s not to be included in report)

(a) Reverse side of card

(2) Risk Questions

1. Do you think he/she will seriously injure or kill you or your children? What makes you think so? What makes you think not?

2. How frequently and seriously does he/she intimidate, threaten, or assault you?

3. Describe most frightening event/worst incidence of violence involving him/her.

(3) Victim Notification

- Provide victim with Crime Victim Information Card (including ICR number and officer’s name)

- Advise of services of local domestic violence shelter

- Advise victim (if there was an arrest) that a volunteer advocate will be coming to her home soon to provide information and support

- If victim has a phone, inform her that the advocate will attempt to call her before coming.

- Contact the battered women’s shelter as soon as possible and advise them of the arrest – 728-6481.

(4) Self-Defense Definition

Reasonable force used by any person in resisting or aiding another to resist or prevent bodily injury that appears imminent. Reasonable force to defend oneself does not include seeking revenge or punishing the other party.

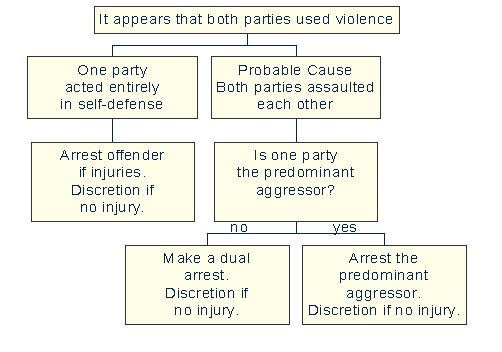

(5) Predominant Aggressor Consideration

Intent of policy – to protect victims from ongoing abuse

Compare the following:

- Severity of their injuries and their fear (incident)

- Use of force and intimidation

- Prior domestic abuse by either party

- Likelihood of either party to commit domestic abuse in the near future.

(See: Duluth Police Pocket Card, StopVAW, The Advocates for Human Rights.)

- Legislation should require the police to inform the complainant/survivor of her rights and options under the law.

For example, the Law of India requires a police officer to inform the victim of important rights:

5. Duties of police officers, service providers and Magistrate. A police officer, Protection Officer, service provider or Magistrate who has received a complaint of domestic violence or is otherwise present at the place of an incident of domestic violence or when the incident of domestic violence is reported to him, shall inform the aggrieved person-

(a) of her right to make an application for obtaining a relief by way of a protection order, an order for monetary relief, a custody order, a residence order, a compensation order or more than one such order under this Act;

(b) of the availability of services of service providers;

(c) of the availability of services of the Protection Officers;

(d) of her right to free legal services under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 (39 of 1987);

(e) of her right to file a complaint under section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (45 of 1860), wherever relevant:

Provided that nothing in this Act shall be construed in any manner as to relieve a police officer from his duty to proceed in accordance with law upon receipt of information as to the commission of a cognizable offence. Ch. III, 5.

Example: Family Violence: A Model State Code, Section 204, describes a comprehensive written notice that police should be required to give to a complainant/ survivor for later review. The Commentary to the Model State Code notes that “An officer may be the first to inform a victim that there are legal and community resources available to assist him or her. Written notice is required because a victim may not be able to recall the particulars of such detailed information given verbally, particularly because the information is transmitted at a time of crisis and turmoil. This written menu of options…permits a victim to study and consider these options after the crisis.”

The notice describes the options which a victim has: filing criminal charges, seeking an order for protection, being taken to safety, obtaining counseling, etc. The notice contains a detailed list of the optional contents for an order for protection. This would be of great assistance to a complainant/survivor who may not be familiar with the purpose of an order for protection. When a complainant/survivor is given a written notice and description of these options, it enables her to consider her options and to decide what is best for her safety and for the safety of her family.

(See: Domestic Violence Legislation and its Implementation: An Analysis for ASEAN Countries Based on International Standards and Good Practices, UNIFEM, June 2009, which states that “Information on rights empowers complainants in negotiating settlements and also allows them to make informed decisions on the legal options that they may want to pursue.” page 22)

Example: Ellen Pence, an expert on the Coordinated Community Response and many other aspects of domestic violence law and policy, recommended that police be trained to expect to see families in conflict numerous times, and to expect that a complainant/survivor may not accept their offer of help the first, second, or even third time. Police must be trained to respect the complainant/survivor’s wishes, and to assist her as she requests. (See: The St. Paul Blueprint for Safety).

(See: Council of Europe, The Protection of Women against Violence Recommendation Rec(2002)5 #29.)