Few rigorous evaluations of what works to prevent and respond to VAWG have been conducted. The evaluations that do exist are often implemented in post-conflict or protracted conflict settings rather than examining the effectiveness of interventions during conflict itself. A few gaps in particular stand out:

- More rigorous reviews of VAWG response programmes to identify best practices and reduce barriers that prevent access to existing survivor service delivery programmes.

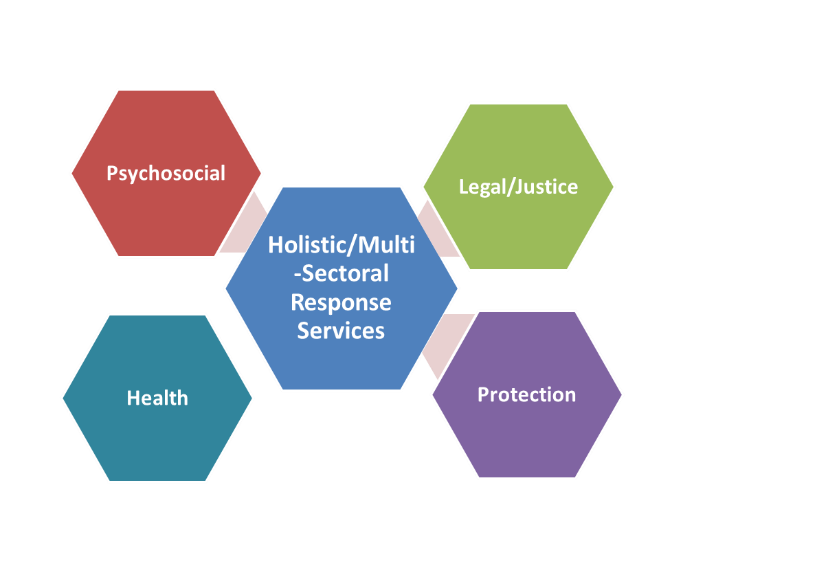

Service delivery programmes in conflict and post-conflict settings should take an integrated approach to case management and psychosocial support for survivors and identify referral pathways for health, protection and legal/justice services as requested by the survivor herself. This approach of creating a supportive environment where the survivor has the right, appropriate to her age and circumstances, to choose what services to access is commonly known as a “survivor-centered approach” (Interagency Gender-based Violence Case Management Guidelines, 2017).

Most studies on service delivery programmes in post-conflict contexts focus on reproductive health outcomes and effectiveness of psychosocial support services, but uptake of these services varies based on the approach and context. The provision of legal support services offers mixed results with some efforts causing re-traumatization of survivors. Furthermore, limited knowledge exists on the effectiveness of service delivery programmes in preventing new incidents of VAWG by reducing perpetrator impunity.

Additional efforts are needed to clearly understand which service delivery approaches result in the best outcomes for survivors and how to reduce barriers to accessing existing services. Particular attention must be payed to intersectionality to understand the unique needs and barriers of women and girls of varying identities (e.g. adolescents, LBGTI, the elderly, etc.) Furthermore, research is needed to understand how and when localization of these services can be achieved and to know if localization of these services effects the sustainability of these services. More evidence is needed to understand the utilization of support services, the effectiveness of case management systems, best practices for legal support service provision to prevent re-traumatization, and approaches that target adolescent girls. More rigorous reviews of service delivery programmes are needed to better identify and evaluate best practices.

Figure 1: Multi-Sectoral Survivor Programming

- Further understanding of how economic empowerment and cash transfer programmes have impacts in VAWG prevention and response.

Some programmes in post-conflict contexts seek to address VAWG through economic empowerment activities including business skill development, livelihoods interventions, vocational training, and village savings and loans approaches. A few rigorously evaluated programmes, such as IRC's EA$E programme in Burundi, show that complimenting livelihoods interventions with conflict mitigation and communication skills have the potential to reduce incidents of VAWG significantly (Holmes & Bhuvanendra, 2014). However, further research is needed to measure the effectiveness of economic empowerment programmes in reducing VAWG in conflict and post-conflict settings.

More research is needed on how best to integrate programmes that target relationship skills or create gender-transformation in order to reduce harm and improve protection outcomes for women and girls who receive cash transfers. A recent study on cash transfers in Raqqa Governorate, Syria is the first mixed-methods study exploring the impact of cash transfer programming on VAWG in an acute conflict setting. It found that while cash transfer recipients were better able to meet basic needs and reported less negative coping strategies, there were increases in reported IPV among participants in the programme (Falb et al., 2019).

- Evaluations of community-based, multi-component interventions, including approaches that challenge patriarchal gender norms in conflict-settings, to understand impact on VAWG and consolidate best practices.

Community-based multi-component interventions are mutli-level interventions that utilize an integrated approach that includes a mix of response services for survivors and VAWG prevention activities. Although community-based multi-component interventions are common in conflict and post-conflict settings, their complex design and community-based approach have resulted in a limited number of evaluations. Despite the challenges in employing rigorous methodology, opportunities exist to use complex evaluation designs in settings such as protracted crises. In such settings, multi-component community-based interventions can and should be evaluated using as rigorous a methodology as possible (e.g. where possible randomized control trials or quasi-experimental evaluations with both an intervention and comparison group).

- Documentation of effective strategies that help to prevent and improve responses to violence against adolescent girls.

More VAWG prevention and response efforts need to include adolescent girls. Girls in this age group face immense social barriers that hinder them from leading safe, healthy and self-sufficient lives. Adolescence is already a very challenging and critical time, and girls are more susceptible to violence, exploitation and abuse during conflict and post-conflict crises. Many girls face additional stigma in accessing essential health services because of their age. Services should therefore be more adaptable to the needs of youth by focusing more on privacy and confidentiality (being mindful of any mandatory reporting laws that should be followed as necessary in settings where they exist), and by finding trusted sources to relay relevant information and dispel misinformation. Although there is a growing body of evidence on the prevalence of physical and sexual violence against girls, there remains a gap in rigorous evidence on effective strategies to prevent and mitigate VAWG risks and protect girls in conflict and post-conflict settings (Murphy et al., 2019).