System-wide review and reform

Undertaking a system-wide review of the education system, with a gender lens and a view to identifying the causes and responses to violence, is a vital early step in developing a holistic response to SRGBV. A process of review and reform that takes a broad look at all parts of the national education sector can help ensure that state education institutions comprehensively address SRGBV through strategies aimed at prevention, response and accountability.

Addressing reform in this holistic way will ensure that opportunities and challenges that exist at different levels are included in any plans to address SRGBV, and will build on existing relevant policies and resources such as those that relate to violence prevention, child protection or the promotion of gender equality. A system-wide approach also provides an opportunity to identify the different partners who need to be engaged and who may already be working on aspects of SRGBV response.

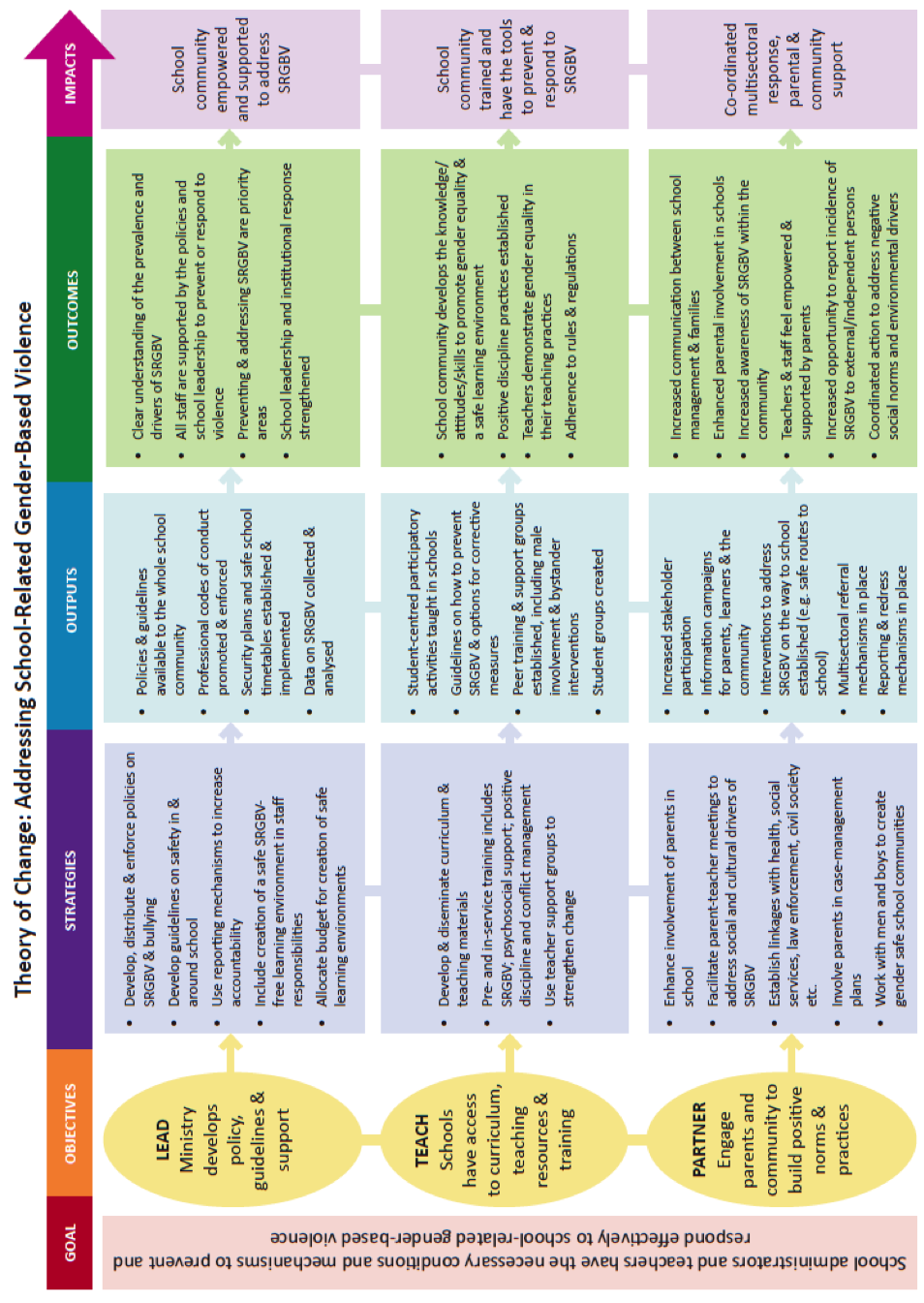

Research by the UNAIDS Inter-Agency Task Team (IATT) on Education and School Health (2015) concluded that comprehensive, systematic and systemic efforts are needed at multiple levels to prevent and address SRGBV and yield better results for empowered school communities. This comprehensive action is represented graphically in the SRGBV Theory of Change (see below). Based on interviews with teachers and other education personnel, the following three overarching objectives for a comprehensive response to SRGBV were identified:

LEAD: Ministry develops policy, guidelines and support.

TEACH: Schools have access to curriculum, teaching resources and training.

PARTNER: Parents and community are engaged to build positive norms and practices.

A system-wide review and reform leads to the development of strategies that are effected at various levels of the education system, sometimes with leadership by different parts of the system itself. These strategies can be seen in Practical action (below) where specific actions are recommended, with links to relevant sections within this guidance.

SRGBV Theory of Change

|

|

Practical action: How can SRGBV be addressed through education system review and reform? |

||

|

Institutional reform can occur throughout the education system at a number of levels: |

See Section: |

||

|

Ministry of Education |

o Support the design, implementation and gender analysis of legislation, national and local action plans, and frameworks on SRGBV |

2.1 Laws and policies 2.1 System-wide review and reform 2.2 Codes of conduct |

|

|

o Ensure gender-sensitive budgets are put in place to raise awareness of and implement new policies and legislation |

|||

|

o Enforce and harmonize legislation and policies for SRGBV, child protection and the prosecution of perpetrators. Ensure codes of conduct are implemented effectively and appropriate sanctions are applied |

|||

|

o Ensure education staff, including teachers, school heads and others, are trained in and equipped to prevent and report SRGBV |

2.3 Pedagogy and teacher training |

||

|

o Mainstream age-appropriate SRGBV prevention-related concepts and skills into national school curriculum development |

2.3 Curriculum approaches to preventing violence and promoting gender equality |

||

|

o Improve referral mechanisms to legal, medical and social services at the national and local levels |

2.4 Referral structures |

||

|

o Develop reporting tools and mechanisms for teachers, school staff and students (peer educators) |

2.4 Reporting mechanisms |

||

|

o Engage with key stakeholders and partners in the design, structures, policy and practice of SRGBV interventions |

2.5 Collaborating with and engaging key stakeholders |

||

|

o Invest in the collection, analysis and sharing of data on SRGBV |

2.6 Monitoring and evaluation of SRGBV |

||

|

Teacher training colleges |

o Include SRGBV in teacher training curriculums and training teachers about the causes of GBV, possible prevention activities, referral and response frameworks |

2.3 Pedagogy and teacher training |

|

|

Teachers’ unions |

o Work with the MoE to develop, implement and revise professional codes of conduct and gender-equitable human resource policies |

2.2 Codes of conduct |

|

|

o Raise awareness of SRGBV among union members, and provide support to teachers affected by SRGBV |

2.3 Pedagogy and teacher training |

||

|

Schools |

o Develop inclusive, gender aware and non-discriminatory school regulations and procedures in line with national guidelines |

2.2 Governing bodies and school management |

|

|

o Create safe and welcoming physical spaces |

2.2 Safe and welcoming schools |

||

|

o Create learning environments with curricula and teaching practices that promote gender-equitable norms, non-discrimination and violence prevention life skills |

2.3 Curriculum approaches to preventing violence and promoting gender equality 2.3 Pedagogy and teacher training |

||

|

o Create mechanisms and strengthen capacity for students to participate in the reduction of SRGBV, for example, through girls’ and boys’ clubs, and by training students as peer educators to detect violence, or as peer mediators |

2.3 Safe spaces and co-curricular activities 2.5 Youth leadership and participation |

||

|

o Make referral to and/or provide guidance counselling and support to victims/survivors of SRGBV |

2.4 Counselling and support |

||

|

o Build and strengthen partnerships with and accountability to communities and families, including through parent–teacher associations, school-based management committees, local communities and groups |

2.5 Community mobilization 2.5 Family engagement |

||

|

Source: Antonowicz (2010); Fancy and McAslan Fraser (2014a) |

|||

|

|

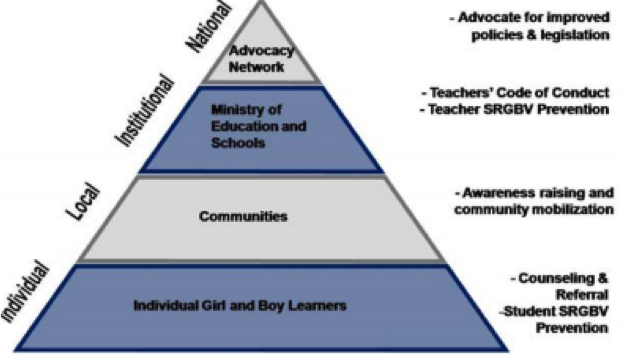

Country example – Implementing a comprehensive reform through multilevel actions |

|

USAID’s Safe Schools model was piloted in Ghana and Malawi from 2003 to 2008 and aimed to reduce violence in and around schools through an integrated set of interventions at the national, institutional, local and individual level. Activities included: national-level awareness-raising activities with a range of stakeholders; a teachers’ Code of Conduct; teacher training to recognize, prevent and respond to GBV; and community-level awareness-raising. A baseline/endline survey of knowledge, attitudes and practices of 800 students and 400 teachers found significant impacts, including: |

|

|

- An increase in teachers’ knowledge of how to report a violation related to SRGBV from 45 per cent (baseline) to 75 per cent (endline). - A change in teachers’ attitudes towards the acceptability of physical violence: in Malawi, prior to the intervention, 76 per cent of teachers thought whipping boys was unacceptable, compared to 96 per cent afterwards. - An increase in teachers’ awareness of sexual harassment of girls and boys at school: in Ghana, there was an increase from 30 per cent to 80 per cent in teachers agreeing that girls could experience sexual harassment at school, and 26 per cent to 64 per cent that boys could also experience sexual harassment. - Students became more confident that they had the right not to be hurt or mistreated: in Ghana, the percentage of students agreeing with the statement ‘You have the right not to be hurt or mistreated’ increased from 57 per cent to 70 per cent (USAID/DevTech, 2008).

|

|

|

The final report recommends that future programmes encourage sustainable, long-term change through a gender approach, a whole-school approach, redefining classroom discipline with teachers and parents, and stressing children’s rights and responsibilities. The Safe Schools pilot has subsequently been rolled out internationally – in the Dominican Republic, Senegal, Yemen, Tajikistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as through a partnership with the Peace Corps. |

|