- Integration is closely linked to the “systems” approach, insofar as its focus is on health delivery organizations, but integration refers more specifically to targeting various types of existing health providers (e.g. emergency rooms, clinics, sexual and reproductive health services, etc.) and determining how violence-related services can be incorporated to ensure that survivors presenting for care (whether or not related to an incident of violence) receive the necessary assistance related to their exposure to violence as quickly as possible.

- Three basic models of integration include:

|

Level of Integration |

Approach |

Example |

|

Provider-level integration |

The same provider offers a range of services during the same consultation. |

A nurse in accident and emergency is trained and resourced to screen for domestic violence, treat her client’s injury, provide counseling and refer her to external sources of legal advice. |

|

Facility-level integration |

A range of services is available at one facility but not necessarily from the same provider. |

A nurse in accident and emergency may be able to treat a woman’s injury, but may not be able to counsel a woman who discloses domestic violence, and may need instead to refer the woman to the hospital medical social worker for counseling. |

|

Systems-level integration |

There is facility-level integration as well as a coherent referral system between facilities in order to ensure the client is able to access a broad range of services in their community. |

A family-planning client who discloses violence can be referred to a different facility (possibly at a different level) for counseling and treatment. This type of integration is multi-site. |

Adapted from Colombini, C., Mayhew, S., and Watts, C., 2008. “Health-sector Responses to Intimate Partner Violence in Low- and Middle-income Settings: A Review of Current Models, Challenges and Opportunities.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86 (8), pgs. 635-642.

- Within the health sector, most violence-related services involve a combination of provider- and facility-level integration; full systems-level integration is rare, in spite of the fact that systems-level integration likely offers the promise of the most comprehensive care within a community. Based on a review of integration efforts in various low and middle-income countries around the world, several key lessons learned about integration include:

- Development and implementation of policies, protocols, and other tools and procedures is important to help institutionalize services as part of care delivery.

- Staff training must be sustained over the long term and support and supervision must be available to providers.

- Integration plans must be careful to address facility infrastructure (including private counseling rooms, availability of appropriate equipment, etc.) as well as documentation systems (see Colombini, Mayhew and Watts, 2008).

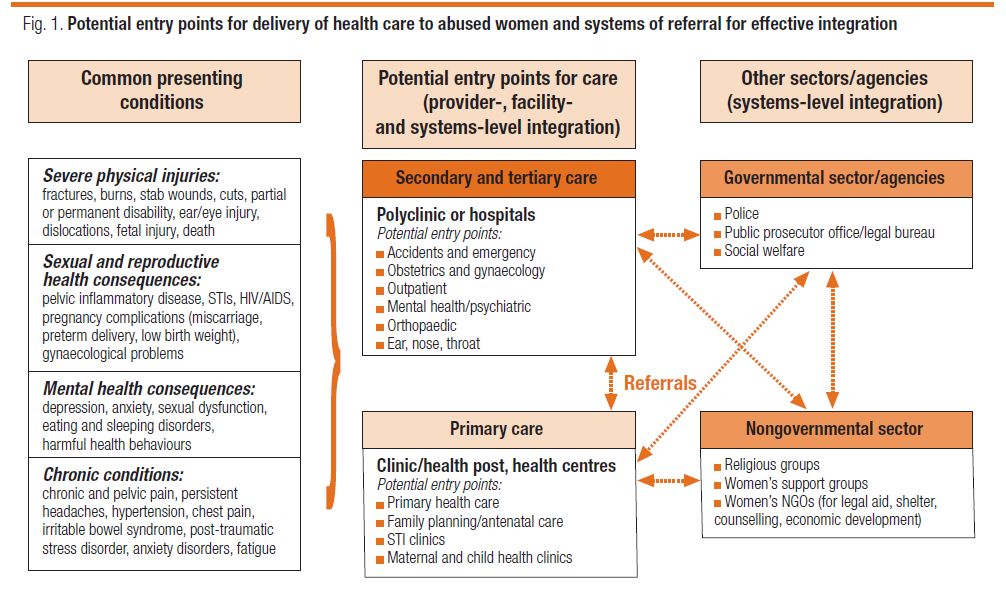

- When considering how to determine what services should be integrated into a specific service delivery organization, it is important to understand the needs of those who are presenting for treatment. The following diagram illustrates some of the common presenting conditions of women experiencing IPV (including sexual violence), the potential entry points at different levels of the system, and the referral networks needed.

Excerpted from: Colombini, C., Mayhew, S., and Watts, C., 2008. “Health-sector Responses to Intimate Partner Violence in Low- and Middle-income Settings: A Review of Current Models, Challenges and Opportunities.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86 (8), pg. 639.

- A sample of issues related to integration in emergency and other services are briefly outlined below:

- Emergency Rooms: Broadly, emergency rooms most often identify violence when survivors present with severe physical injuries and/or when rape victims are seeking emergency treatment. Evidence suggests that most women and girls experiencing rape will go to a hospital before going to the police, and may be reluctant to go to the police for safety (fear of retaliation) and economic reasons (fear of loss of financial support resulting from imprisonment of her partner). For post-sexual violence visits in particular, there is a crucial 72-hour period in which HIV Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) is possible, and 120 hours for emergency contraception (and up to five days if an IUD is used—which it rarely is in cases requiring emergency contraception), strongly arguing for 24-hour availability of services, use of facility-level integration, and “one-stop services.”

- Primary care (MCH), HIV and other Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: In primary care and sexual and reproductive health entry points, the health consequences of violence may be a presenting condition, but women typically will not disclose their experience of violence unless asked. Therefore, policies and protocols for inquiry become a crucial component when planning for integration, including decisions on whether to implement universal screening or screening only in selected services such as HIV Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT), family planning, and the emergency room. (For more information about implementing screening, see Consider Routine Screening.)

Common challenges in implementing a comprehensive approach

- There are many challenges within the health sector to employing the ecological, multisectoral, systems-based and integrated models for addressing violence against women and girls. These challenges must be anticipated when developing and implementing policies and programming:

- Insufficient evidence base. Although there are numerous anti-violence against women and girl’s initiatives taking place in various parts of the world, many of them are quite small and few have been rigorously evaluated and/or documented. When evaluations have been implemented, their scope, depth, methodological approach and overall quality tend to be uneven. The majority of rigorous health sector evaluations have been undertaken in North America and Western Europe, making it challenging to extrapolate the findings to other regions and contexts (Feder et al., 2009; Ramsay, Rivas and Feder, 2005). These evaluations also tend to focus on one specific aspect of health care, such as screening or provider training, rather than on systems-based approaches or national level interventions. Developing a health surveillance system and conducting monitoring and evaluation are critical to improving programming efforts (United Nations, 2006a).

- Lack of coordination. Programmes too often operate independently of one another, failing to build on mutual resources to plan and implement comprehensive services (Colombini, Mayhew and Watts, 2008). Developing multisectoral national coordination networks and ensuring coordination and referral is critical to efficient and effective programming (United Nations, 2006a).

- Poor legal/policy framework. National laws and policies regulating domestic violence, sexual violence, harmful traditional practices such as FGM/C and child marriage, inheritance rights, marriage and divorce vary widely throughout the world and can even be inconsistent or conflicting within various domestic frameworks. Even still in settings where comprehensive laws and policies addressing violence against women and girls exist and are aligned, there are challenges in ensuring their implementation, due to lack of technical and financial resources, coordination, and prioritization of violence issues (USAID and UNICEF, 2006). Developing legislation on violence against women and girls, including in the context of HIV and AIDS, is the basis for prevention and response programming. Within the health sector, it is important to review relevant laws and, when necessary, conduct advocacy to upgrade laws.

- Lack of financial and technical resources. Ministries of Health operating at national, district and local levels face numerous demands with often limited financial and human resources. As a result, violence against women and girls is rarely prioritized and budgeted for, despite the substantial costs of violence against women and girls to the individual, family, society and to public health. Ensuring funding is key to building effective programming.

- Lack of minimum standards for services. Minimum Standards represent the lowest common denominator that all states and services should aim to achieve. Standards provide benchmarks- for states and service providers – with respect to both the extent and mix of services which should be available, who should provide them, and the principles and practice base from which they should operate. For example, according to a review of forty-seven European countries, standards have yet to be formalised in most (Council of Europe, 2008a). The Council of Europe (2008a) has recommended minimum standards for various violence programming, including 24-hour hotlines, sexual assault centres in hospitals and rape crisis centres.

- Individual service providers’ attitudes and lack of knowledge about violence. Service providers may promote unhelpful or even hurtful attitudes and practices due to insufficient training, high turnover of trained staff, lack of inclusion of violence-response training in national medical curricula, etc. (Kim and Motsei, 2002; Colombini, Mayhew and Watts, 2008). Staff may also have been exposed to violence themselves, which may limit their capacity to effectively engage with clients. Staff sensitization, specialized training, and on-going supervision and staff support are key to ensuring supportive responses to survivors.

- Managerial and health systems’ challenges. These might include a lack of clear institutional policies on violence, entrenched medical hierarchies, lack of coordination among various actors and departments involved in planning integrated services, and lack of commitment by administrators (Colombini, Mayhew, and Watts, 2008). Conducting facility assessments and developing policies and protocols to address gaps in services are key to overcoming health systems’ challenges (Troncoso et al., 2006).

- Lack of prevention activities. Due to the bio-medical orientation of the health sector, there is often a failure among health institutions and agencies to undertake broad-based prevention activities that target attitude and behaviour change at the community level. However, prevention programming should be considered an integral part of health facilities’ work on violence against women and girls.