Brief overview of monitoring and evaluation of initiatives for women and girls in conflict, emergency or displaced situations

- The knowledge base of multisectoral programming to address gender-based violence among displaced populations has grown since the 1990s. Inter-agency programming has become the norm with the development of comprehensive programmes that integrate multiple sectors.

- Initiatives have focused mainly on health care, especially reproductive health, emotional support, social reintegration, police and legal intervention. Prevention strategies are newer, involving refugee and displaced communities in changing norms around violence.

- Specific guidelines for multisectoral interventions to prevent and respond to violence against women in these settings, codes of conduct for humanitarian, security and other actors, and tools for conducting situation analyses, monitoring and evaluating interventions have also been developed, although they have not necessarily been widely incorporated.

- Despite these advancements, there are few published evaluations of such programmes given the challenging context to undertake assessments in such settings.

- Improving prevention, protection, punishment and response measures is critical given the large numbers of women and girls that suffer abuse in these settings.

- Monitoring and evaluation in conflict/post-conflict/emergency and displaced situations is crucial to maintaining and improving the coordination of efforts among the various non-governmental and governmental actors; and in developing national capacities to prevent and respond effectively in situations that are protracted and require sustained prevention and response efforts.

- Monitoring and evaluation also serves to ensure that women and girls have safe access to humanitarian assistance and basic amenities, such as water, food, fuel and sanitation, since they are often at heightened risk of sexual attack when undertaking routine daily tasks to obtain these amenities. For girls, this includes accessing education.

- Monitoring the provision and uptake of services is especially important to make sure that women and girls are receiving the medical, psychosocial and legal services they need and to mitigate the negative lifelong consequences that can affect post-conflict recovery, integration and development.

General Guidance

- Humanitarian organizations considering the addition of a violence against women programme to their portfolio may believe that they need to survey the women and children in the population to quantify prevalence and gather baseline data, but a survey is probably not necessary in the early phases. Building in-depth knowledge of survivor needs and community attitudes is a process that occurs over time.

- A survey may also be inappropriate because the risks might outweigh the benefits. Violence against women and girls is a hidden problem, and a number of ethical and safety concerns must be taken into account before any surveys are conducted. Disclosing violence may prove even more challenging for survivors in emergency situations, which are characterized by instability, insecurity, fear, dependence and loss of autonomy, as well as a breakdown of law and order, and widespread disruption of community and family support systems.

- If survivors self-report and no services are in place to assist them, the survey may do more harm than good, opening emotional wounds that cannot be closed without follow-up support. More important, surveys may endanger a survivor: if the perpetrator knows she is a survey respondent, he may retaliate; security systems may be inadequate to protect her.

- Because various types of violence against women occur in every conflict and nearly every culture, it is safe to assume at the outset of any programme that there are gender-based violence survivors with unmet needs in displaced populations. The situation analysis will provide enough information to get the programme started without endangering survivors or the viability of the programme. Surveys may be useful, and necessary, for programme development after support services are ready to step in.

- It is often very difficult, and sometimes impossible to collect the kind of information desired for a baseline assessment especially during the early stages of emergency, disaster or conflict response. It is however critical to conduct some basic form of assessment of the nature and scope of violence, to evaluate the capacity of humanitarian actors and host communities to provide services to survivors of sexual violence and exploitation and to institute protective mechanisms to prevent additional incidents from occurring; as well as to raise decision-makers’ and humanitarian actors’ awareness about the risks of sexual violence, and encourage utilization of key guidelines and resources to ensure rapid implementation of prevention and response programming. (Vann, 2002)

Conducting a situation analyses and assessments

The situation analysis is a review of the situation at hand providing an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of services available and the needs in the target population. It can provide information on the type(s) and extent of sexual violence experienced by the community; the policies, attitudes, and practices of key actors within the health, psychosocial, security, human rights, and justice sectors and within the community.

Even during the early phase of a new emergency, while the population is on the move and the setting insecure, basic information on the nature and extent of sexual violence can be gathered. In line with ethical guidelines, services should be in place to address survivors and gaps in services to prevent and respond to sexual violence should be undertaken.

During an emergency, multiple actors (e.g. government authorities, international organizations and others) conduct assessments on gender-based violence. To avoid duplication and repeat interviews with the target population(s), information should be shared among actors. These assessments can be conducted on a periodic basis, using the same tools and methodology, in order to determine changes in the environment and make adjustments.

- Collect information in accordance with guiding principles for safety, confidentiality, respect, and non-discrimination; and ensure all documents maintain the interviewees anonymity and are stored securely.

- Methods for collecting information should involve the community and may include semi-structured interviews, site visits, and observation of the environment.

- Secondary information sources that may be useful includes existing needs assessments, reports, and available data related to sexual violence.

- Use techniques that will gain rather than alienate community and individual trust, incorporating cultural sensitivity and extreme care in discussing sensitive topics.

- Use same-sex interviewers and interpreters.

- Ideally information should be gathered by multidisciplinary teams.

(Inter-agency Standing Committee Guidelines, 2005)

A situation analysis should consider collecting and analyzing information on the following:

- Type and extent of GBV taking place.

- Formal and informal community systems for conflict resolution and leadership.

- Attitudes, knowledge, and behavior of the community, host government staff, and humanitarian aid staff (especially in key response organizations) regarding gender, human rights, power, and GBV.

- Ability of the community, host government staff, and humanitarian aid staff to meet survivor needs with the services available (e.g. staffing, protocols, and equipment).

- Training for the community, host government staff, and humanitarian aid staff to meet survivor needs.

- Mechanisms for interagency and interdisciplinary coordination.

- Extent (and effectiveness) of interagency and interdisciplinary communication and collaboration.

- Perpetuating factors in the setting that contribute to incidents of GBV and prevention activities already underway, including staffing and training. (Vann, 2002)

- Demographic information, including disaggregated age and sex data

- Description of population movements (to understand risk of sexual violence)

- Description of the setting(s), organizations present, and types of services and activities underway

- Overview of sexual violence (populations at higher risk, any available data about sexual violence incidents)

- National security and legal authorities (laws, legal definitions, police procedures, judicial procedures, civil procedures)

- Community systems for traditional justice or customary law

- Existing multisectoral prevention and response action (coordination, referral mechanisms, psychosocial, health, security/police, protection/legal justice). (Inter-agency Standing Committee, 2005)

(Adapted from Vann 2002; Inter-agency Standing Committee, 2005; and Reproductive Health Response Conosrtium, 2004)

See also the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Initial Rapid Assessment: Field Assessment Form.

Once the situation analysis is complete, the findings should be documented and distributed to all stakeholders, including the community and donors. These findings should guide the design of the programme and development of the monitoring and evaluation framework.

Data generated from a situational analysis can be used to mobilize community leaders of the need for programming. In addition, the process of conducting a situational analysis can itself be an intervention, by initiating a public discussion of violence and opening dialogue with key institutional actors. The situational analysis should be used as a tool to instruct as much as to investigate. It is strongly suggested that those using the tool are members of the local community, with an interest in using knowledge gained from the analysis to improve programming. Local researchers should not only participate in and lead the process, but should also be actively engaged in reviewing results and developing action plans. (Reproductive Health Response Conosrtium, 2004)

Case Study: Post-election Violence in Kenya Rapid Assessment

Despite numerous challenges found in conflict, emergency and post-conflict settings, including the brevity of field visits, difficulty reaching internally displaced persons and refugees, lack of coordination inherent in early stages of emergency response, ongoing movements of the displaced, large number of informal encampments, security and logistical issues limiting access to certain sites, and availability of translators, a joint interagency team (UNFPA, UNICEF, UNIFEM and the Christian Children’s Fund) was able to create a fairly comprehensive picture of the situation for women and girls following the post-election violence in Kenya.

The rapid assessment conducted during the post-election crisis in Kenya from January-February 2008 drew on several of the resources presented in this module. Investigative methods primarily included key informant interviews with provincial and district government partners, humanitarian field workers, and representatives of agencies working in the legal, security, health, and psychosocial sectors. Wherever possible, meetings were held with male and female camp representatives and focus groups were conducted with displaced women and men.

See the full report: A Rapid Assessment of Gender-based Violence During Post-Election Violence in Kenya. Available in English.

Indicators

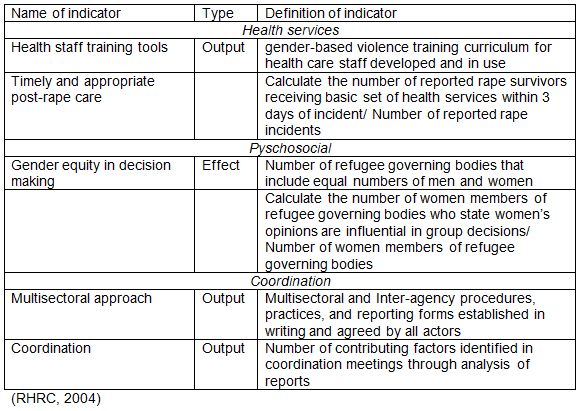

MEASURE Evaluation, at the request of The United States Agency for International Development and in collaboration with the Inter-agency Gender Working Group, compiled a set of indicators for conflict/post-conflict/emergency settings. The indicators have been designed to measure programme performance and achievement at the community, regional and national levels using quantitative methods. Note, that while many of the indicators have been used in the field, they have not necessarily been tested in multiple settings. To review the indicators comprehensively, including their definitions; the tool that should be used and instructions on how to go about it, see the publication Violence Against Women and Girls: A Compendium of Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators.

The compiled indicators for conflict/post-conflict/emergency settings are:

- Protocols that are aligned with international standards have been established for the clinical management of sexual violence survivors within the emergency area at all levels of the health system

What It Measures: This indicator measures whether or not there is a sound clinical protocol in place to ensure that sexual violence survivors are cared for appropriately within the health system of an emergency area. However, it does not measure adherence within the health units.

- A coordinated rapid situational analysis, which includes a security assessment, has been conducted and documented in the emergency area

What It Measures: This indicator measures whether a situational analysis aimed at the prevention and response of VAW/G has been completed for a given emergency area, using internationally validated tools. The choice of tools and how much of each to be incorporated is up to the coordinated body undertaking the assessment and depends on the context of the situation.

- The proportion of sexual violence cases in the emergency area for which legal action has been taken

What It Measures: This indicator measures the extent to which legal recourse is taken for reported cases of sexual violence. If there is a very low proportion of cases that have had the minimum legal action defined as acceptable, this would indicate that the legal structure in the emergency area is not adequate. A high proportion of reported cases for which legal action was taken would indicate a legal system functioning at a high level of protection for women and children within the area.

- Proportion of reported sexual exploitation and abuse incidents in the emergency area that resulted in prosecution and/or termination of humanitarian staff

What It Measures: This indicator measures an adherence to the minimum prevention and response protocol pertaining to the conduct of humanitarian staff. Many studies have noted that numerous sexual exploitation and abuse incidents in emergency areas are perpetrated by the very people who are employed to protect the victims of humanitarian emergencies. A demonstrated zero tolerance for such incidents means that once reported and confirmed persons responsible will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law, or at minimum, terminated from their position to protect the women and girls under their care.

- Coordination mechanisms established and partners orientated in the emergency area

What It Measures: This indicator measures whether or not multiple agencies involved in the response to an emergency are working together with respect to the prevention and response to sexual exploitation and abuse. The criteria listed can be taken as a minimum list of what should be done with respect to coordination and orientation of partners.

- Number of women/girls reporting incidents of sexual violence per 10,000 population in the emergency area

What It Measures: This estimates the number of reported sexual violence incidents per a standard number of people. Using this standardization will allow for a comparison to be made across time in the same location, or between locations.

- Percent of rape survivors in the emergency area who report to health facilities/workers within 72 hours and receive appropriate medical care

What It Measures: This indicator measures whether or not health facilities provide the appropriate comprehensive care to rape survivors who present within 72 hours of the incident. If survivors present after this period, services such as PEP and emergency contraception would not be part of the care that health service delivery points should be expected to provide.

- Proportion of sexual violence survivors in the emergency area who report 72 hours or more after the incident and receive a basic set of psychosocial and medical services

What It Measures: This indicator measures whether or not health facilities provide the appropriate basic psychosocial and medical care to sexual violence survivors, including rape survivors, who present to health service delivery points 72 hours or more after the incident occurred. The list of basic services can be drawn from chapter 4 of the UNHCR field manual.

- Number of activities in the emergency area initiated by the community targeted at the prevention of and response to sexual violence of women and girls

What It Measures: This is a measure of how involved the community is in ensuring that women and children are safe within the emergency area.

- Proportion of women and girls in the emergency area who demonstrate knowledge of available services, why and when they would be accessed

What It Measures: This measures important aspects of access to available community resources to prevent and respond to VAW/G. Availability of resources by itself will not mean much if women are not aware of them, and if they do not know why or when they would access them. However, this does not measure whether women are able to physically get to the resources when they need them.

The Inter-agency Standing Committee Guidelines recommend that programmes establish at least one indicator for response in each sector (health, psycho-social, security, legal/justice), at least one indicator about coordination, and at least one indicator related to prevention as well as activity indicators to monitor activities.

The IASC Guidelines also include a Sample Monitoring Form for the Implementation of Minimum Prevention and Responses. Indicators for monitoring each of the functions/ sectors should be developed with at least one indicator per function/sector. The indicators below are illustrative

Situation/Country: _________________ Date:_________________

Completed by: _________________

|

KEY ACTIONS STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION |

|

|

Coordination |

|

|

1.1 Establish coordination mechanisms and orient partners 1.2 Advocate and raise funds 1.3 Ensure Sphere standards are disseminated and adhered to |

|

|

Assessment and Monitoring |

|

|

2.1 Conduct a coordinated situational analysis 2.2 Monitor and evaluate activities |

|

|

Protection |

|

|

3.1 Monitor security and define protection strategy 3.2 Provide security in accordance with needs 3.3 Advocate for implementation of and compliance with international instruments |

|

|

Human Resources |

|

|

4.1 Recruit staff in a manner that will discourage SEA 4.2 Disseminate and inform all partners on codes of conduct 4.3 Implement confidential complaints mechanisms 4.4 Implement SEA focal group network |

|

|

Water and Sanitation |

|

|

5.1 Implement safe water/sanitation programmes |

|

|

Food Security and Nutrition |

|

|

6.1 Implement safe food security and nutrition programmes |

|

|

Shelter and Site Planning and Non-Food Items |

|

|

7.1 Implement safe site planning and shelter programmes 7.2 Ensure that survivors/victims have safe shelter 7.3 Implement safe fuel collection strategies 7.4 Provide sanitary materials to women and girls |

|

|

Health and Community Services |

|

|

8.1 Ensure women’s access to basic health services 8.2 Provide sexual violence-related health services 8.3 Provide community-based psychological and social support |

|

|

Education |

|

|

9.1 Ensure girls’ and boys’ access to safe education |

|

|

Information, Education, Communication |

|

|

10.1 Inform community about sexual violence and the availability of services 10.2 Disseminate information on IHL to arms bearers |

|

Monitoring

The Inter-agency Standing Committee Guidelines recommend monitoring implementation of minimum prevention and responses to sexual violence by ten functional/sectoral areas. Those involved in gender-based violence response should agree on the frequency and methods for monitoring and documenting progress in implementation.

In the very early stages of an emergency when minimum prevention and response actions are starting up, progress must be monitored weekly or more frequently to ensure rapid start-up and address any obstacles or delays.

When implementation of minimum actions are well underway, progress may be monitored monthly, again addressing obstacles or delays, and continuing until all key actions have been implemented.

In general, data should be collected on reported incidents of sexual violence and compiled into a report, making sure that it contains no potentially identifying information about survivors/victims or perpetrators.

The report should be compiled regularly and consistently; the data reviewed and analyzed in working group meetings; and the information used to strengthen prevention and response actions.

Information should be compared over time, identifying trends, problems, issues, successes and other relevant data. The report should be distributed to key stakeholders, including the community and local authorities; and community meetings should be initiated to discuss the information and strategies to improve prevention and response, especially ensuring the active participation and input from women and girls.

Illustrative data that should be collected to monitor responses:

Data Elements of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Reports: It is essential that certain information be collected in reports. To be effective, all actors must agree on the terminology used so that reporting forms are comparable. All reporting mechanisms must ensure the confidentiality of the victim/survivor and perpetrator.

- Data Elements for Monthly Report Forms:

-Total number of incident reports.

-Types of sexual and gender-based violence perpetrated.

-Number, age and sex of victims/survivors.

-Number, age and sex of perpetrators.

-Number of incidents by location (e.g. house, market, outside camp [indicating -where outside the camp]).

-Number of rape victims/survivors receiving health care within two days of incident.

- Data Elements for Legal Form:

-Number of cases reported to the protection officer.

-Number of cases reported to the police.

-Number of cases taken to trial.

-Number of cases dismissed.

-Number of acquittals/convictions.

-Types of sexual and gender-based violence perpetrated.

-Number of rape cases seen within two days by health services.

-Number of cases in which forensic medical evidence was prepared.

-Percentage increase/decrease of number of rape cases by month.

-Percentage increase/decrease of sexual and gender-based violence incidents by month.

-Additional observations.

- Data Elements for Situation Reports:

-Sexual and gender-based violence concerns, issues, and incidents.

-Status of co-ordination and planning.

-Prevention interventions by sector.

-Response interventions by sector.

-Staff/beneficiary capacity training.

-Protection impact: monitoring and evaluation activities.

(United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2003)

Illustrative tools and methods for monitoring:

- The Incident Report Form is an important reporting tool that should be used by all actors. When any incident of sexual and gender-based violence is reported to any actor, there should be a standard format used to record such incidents.

- The Monthly Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Report Form. This reporting mechanism is important for tracking the changes in the environment that affect the incidence of sexual and gender-based violence. This report also provides insights into the factors that may perpetuate these acts of violence at the community level. For the monthly report form, keep in mind that data must be compiled for each individual setting; totals provided for the field office, regionally or countrywide are also useful.

- The Mapping Guidelines are designed to enable communities to participate in identifying their own needs. Community members identify geographic, demographic, historic, cultural, economic, and other factors within their communities that may exacerbate gender-based violence.

- Focus groups are particularly helpful in the early stages of programme development because they provide in-depth information about participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours related to violence against women. Because they can be conducted with relatively limited resources, they are also a cost-effective, efficient method. Focus groups raise awareness and spark dialogue, and are a valuable component of participatory planning and programming.

- The Pair-wise Ranking Guidelines allow community members to collectively determine their most significant gender-based violence-related problems or issues through a systematic listing and graphing exercise. By obtaining information about how communities rank gender-based violence problems, programmes are better equipped to prioritize prevention and response strategies.

- The Causal Flow Analysis Guidelines allow investigators to delve more deeply into an issue with the assistance of community members. They provide a framework for looking at causes and effects of gender-based violence, and a method of diagramming the problems for a visual inspection.

- The Draft Prevalence Survey Questionnaire is designed for collecting data on the prevalence of gender-based violence in a community. Research initiatives have illustrated that good quality prevalence data are essential to fully assess the nature and scope of gender-based violence, to design appropriate interventions, and to advocate for improved policies to protect survivors and to reduce rates of gender-based violence. However, conducting a methodologically and ethically sound gender-based violence prevalence survey requires extensive technical and financial resources, and therefore may not be warranted in some situations. This tool is included for reference and research planning purposes, and should only be used by those with extensive gender-based violence research experience.

- The Sample Interviewer Training Handbook provides an example of some of the areas of concern in preparing for population-based research and developing survey questions.

- The causal pathway framework a method for designing and implementing programmes that follows a logical progression towards an intended goal.

- The Consent for Release of Information Form must be used to secure consent from individuals whose information the organization will be disclosing to other organizations or individuals. It is the responsibility of the gender-based violence staff to maintain beneficiaries’ confidentiality.

- The Client Feedback Form facilitates compiling data from beneficiaries of gender-based violence programmes. This will provide important information on what beneficiaries believe are the strengths and weaknesses of the programme, especially in terms of service delivery. (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2003; Reproductive Health Response Conosrtium, 2004)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Resources:

Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings: Focusing on Prevention of and Response to Sexual Violence in Emergencies (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2005). The guidelines are available in Arabic, Bahasa, English, French and Spanish.

Gender-based Violence Tools Manual for Assessment & Programme Design, Monitoring & Evaluation in conflict-affected settings (The Reproductive Health Response in Conflict Consortium, 2003). Available in Arabic, English and French.

Gender Handbook in Humanitarian Action: Women, Girls, Boys, and Men: Different Needs - Equal Opportunities (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006). Available in Arabic, English, French, Russian and Spanish.

The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response. (The Sphere Project, 2004). The handbook is available in Arabic, Azerbaijani, Burmese English, Farsi, French, German, Korean, Pashtu, Russian, Spanish, Tamil, Turkish and Urdu.

Gender-Based Violence Information Management System (International Rescue Committee, UNHCR and UNFPA, 2009). An overview of the system is available in English.

Reproductive Health Assessment Toolkit for Conflict-Affected Women (Centers for Disease Control). Available in English.

A Guide to Monitoring and Evaluation of NGO Capacity Building Interventions in Conflict Affected Settings (Fitzgerals, Posner, Workman/JSI Research and Training Institute, Astarte Project, 2009). Available in English.

Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings (Save the Children and UNFPA. 2009). Available in English.

Sexual and Gender-based Violence against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons: Guidelines for Prevention and Response (UNHCR, 2003). Available in English.

Checklist for Action: Prevention & Response to Gender-based Violence in Displacement Settings. (Gender-Based Violence Global Technical Support Project RHRC Consortium/JSI Research and Training Institute, 2004. Available in English.

Handbook for the Protection of Women and Girls (UNHCR, 2008). Available in English.

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2003). Available in English.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------