- A legal and policy framework is essential to holding security actors accountable for addressing VAWG. Developing such a framework entails securing political commitment from the highest levels of leadership and management within the sector to implement strategies and polices related to prevention of and response to VAWG. This commitment can then be actualized by:

- Putting in place national laws with specific measures for police and other uniformed personnel to uphold women’s and girls’ right to live free of violence.

- Instituting national policies, strategies and action plans that set out roles and responsibilities of different security actors and are budgeted for implementation.

- Developing institutional policies, operational policies and codes of conduct to promote zero tolerance for violence against women and guide the work of police and other uniformed personnel in areas such as incident response, protection of survivors, investigation, and referrals.

- Depending upon the specific context and type of policy, a broad range of actors can be involved in policy-making, including international, regional, national and local stakeholders. Different types of policies and agreements which address SSR and provide an opportunity for response to VAWG in conflict and post-conflict settings include:

- National security policies (including National policies on UN SCR 1325) Examples: Securing an Open Society: Canada’s National Security Policy, National Security Concept of Georgia

- Peace agreements (while not ‘SSR policies’, they serve as a framework for SSR in many post-conflict contexts) Examples: Liberian Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Guatemalan Peace Accords

- National, regional and international codes of conduct Examples: OSCE Code of Conduct on Politico- Military Aspects of Security, UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials

- Donor policies and strategies Examples: Security Sector Reform: Towards a Dutch Approach, The Norwegian Government’s Action Plan for the Implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000)

- International and regional organisations’ policy frameworks Examples: OECD DAC Ministerial Statement: Key Policy and Operational Commitments from the Implementation Framework for Security System Reform, Commission of the European Communities’ A Concept for European Union Support for Security Sector Reform

- Institutional and municipal level policies

- White papers (government policy papers that often precede the development of legislation) on security, defence, intelligence, police

- Local citizen security plans (adapted from Valasek, 2008).

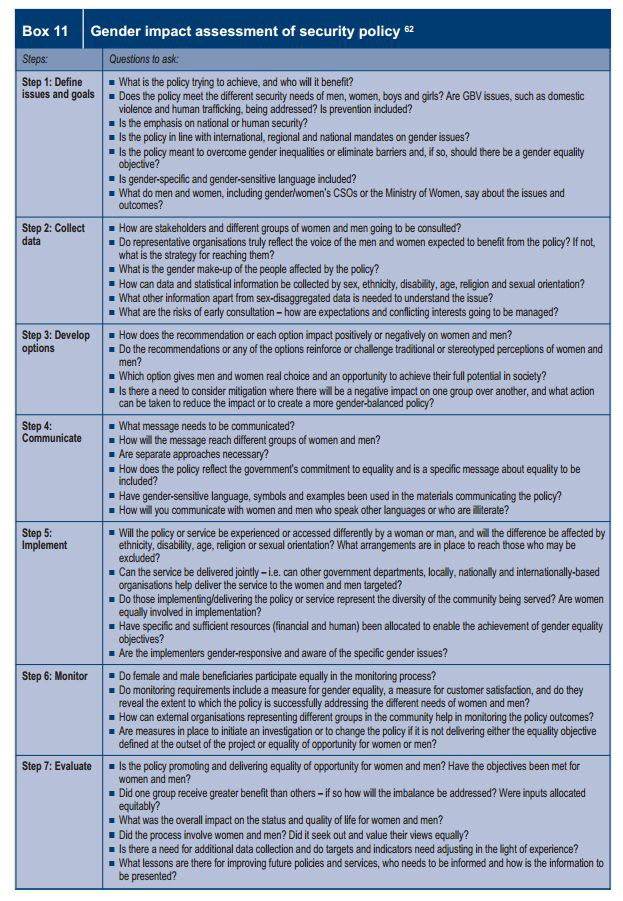

- When developing legal and policy frameworks which mandate the security sector to address violence against women and girls, it can be useful to conduct an initial assessment to determine gaps in existing frameworks. It is also critical to monitor implementation of policy(ies) and conduct on-going impact assessments (Valasek, 2008).

Source: Valasek, K. 2008. “Security Sector Reform and Gender.” In Bastick, M & Valasek, K. (eds.) Gender and Security Sector Reform Toolkit, pg. 13. Geneva: DCAF, OSCE/ODIHR, and UN-INSTRAW.

Example: Implementing SCR 1325 through National Actions Plans.

Côte d’Ivoire has been experiencing political and military crises since September 2002. Its five-year 1325 NAP, covering the period 2008 – 2012, was designed under the lead of the Ministry of Family, Women and Social Affairs (MFWSA), with the collaboration of various other relevant ministries. In January 2007, UNDP, UNFPA, the Gender Unit of the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire, UNIFEM and the government of Norway launched a project to provide technical and financial support to the drafting and implementation process and to support civil society organisations involved in gender issues to participate in the 1325 NAP process. Under this project, training on SCR 1325 was conducted for government officials, locally elected representatives—especially mayors and general counsellors--and civil society organisations.

Côte d’Ivoire’s 1325 NAP contains a detailed overview of the gender-based insecurities that women and girls in Côte d’Ivoire face, including internal and external displacement, prostitution, sexual violence and assault. It also acknowledges that security sector institutions face problems such as corruption and politicisation of the judicial environment, and that there is a lack of training for the police and the gendarmerie to deal effectively with victims of sexual violence. These problems are impeding efforts to effectively address the gender-based insecurities of women and girls. Recognizing the importance of addressing women’s needs and including women in all development sectors, the 1325 NAP states that the implementation of SCR 1325 is a national priority. As such the 1325 NAP constitutes a consensual framework for reconstruction, reconciliation and sustainable peace in the country.

The overall objective of Côte d’Ivoire’s 1325 NAP is to “integrate the gender approach in the peace policy in order to reduce significantly inequalities and discriminations”. To accomplish this aim, the 1325 NAP identifies four priority areas:

- Protection of women and girls’ rights against sexual violence, including female genital mutilation

- Inclusion of gender issues in development policies and programmes

- Participation of women and men in national peace and reconstruction processes

- Strengthening of women’s participation in political decision-making and the political process

A prominent feature of Côte d’Ivoire’s 1325 NAP is that it sets out a logical framework of indicators for a chain of results linked to each of its four priority areas (see pages 27-33), offering a platform for monitoring and evaluation of progress. Each priority area includes 6 -12 actions and three different types of results - “strategic results”, “effect results”; and “output results”. For each of the actions, a responsible party and a reporting method are identified. The logical framework also identifies risks and defines output indicators, verification sources and verification means for each of the desired results. Moreover, the 1325 NAP includes a five-year budget plan broken down by activity (adapted from DCAF, 2011, pgs. 68-70).

Example: Post conflict needs assessment in Liberia.

In Liberia, the post-conflict needs assessment (PCNA) started after the Security Council deployed the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) on 19 September 2003. The newly installed National Transitional Government of Liberia and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General agreed that an assessment of Liberia’s needs during the official “transition period”—from 14 October 2003 to 31 December 2005—was required to secure both donor engagement and funding. The PCNA, known as the “Joint Needs Assessment”, identified human rights, protection, and gender as cross-cutting themes. To assist integration of gender into each priority area, the UN Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and the Advancement of Women prepared a “Gender Checklist for Liberia.” The underlying idea was that determining the differences in how women, men, boys and girls experience conflict would help the assessment team to identify their respective needs and priorities. In particular, understanding the role women play in all sectors of activity (economic, social, cultural, political, etc.) would help ensure that reconstruction activities were planned in a way that would not reinforce past discrimination, and would help women to gain equal access and control over resources and decision-making processes. The focus on gender in the Joint Needs Assessment highlighted how Liberian women have unequal access to areas such as education, public administration, the justice and political systems, and development and post-conflict peace building efforts more broadly and called for specific actions to be taken to address the problem. That gender was integrated into the PCNA in Liberia from its inception allowed gender-related issues and concerns to be raised during the Liberia Reconstruction Conference, with calls for donors’ acknowledgement of and attention to the gendered dimensions of the Liberian conflict and post-conflict reconstruction efforts. Furthermore, the findings of the PCNA process in Liberia influenced, at least in part, the integration of gender into the security sector reform process

Source: adapted from DCAF, 2011, pgs. 86-91.

Additional Tools

Gender and Security Sector Reform: Examples from the Ground (The Geneva Center for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF), 2011). Concrete illustrations of ways in which a gender perspective has been integrated in different security sector institutions and security processes around the world. They can help policymakers, trainers and educators better understand and demonstrate the linkages between gender and SSR. Available in English.

Gender and Security Sector Reform Training Resource Package (The Geneva Center for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF), 2009). This Training package provides practical training materials on Gender and Security Sector Reform. A companion to the SSR and Gender Toolkit, the Training Package is designed to help SSR trainers and educators present material on gender and SSR in an interesting and interactive manner. It contains a wide range of exercises, discussion topics and examples from the ground that can be adapted and integrated into other SSR trainings. Available in English.

See also the Legislation Module.