- During the acute phase of an emergency the priority is to provide a Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) to ensure that basic health needs are met (including basic counselling) and in order to mitigate negative long-term effects of violence on survivors. Once the acute stage has passed and the emergency moves into the post-conflict/recovery phase programs can shift focus to more sustainable solutions through the capacity building of the health sector for a comprehensive approach to responding to violence against women and girls.

- The MISP is a coordinated series of priority actions designed to prevent and manage the consequences of sexual violence against women and girls, prevent reproductive health-related morbidity and mortality, reduce HIV transmission and plan for comprehensive reproductive health services in the early phase of emergency situations (IASC, 2005; Women’s Refugee Commission, 2006, revised 2011).

- The MISP forms the basis for sexual and reproductive health programming in conflict and post-conflict settings. It should be implemented at the onset of an emergency and should be sustained and built upon with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services throughout protracted crises and recovery phases (Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises, 2009). The MISP includes the implementation of life saving activities and actions that prevent illness, trauma and disability, especially among women and girls. As a result, the MISP meets the life‐saving criteria for the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) (Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises, 2009).

- The MISP can be implemented without conducting new needs assessments due to existing documented evidence that justifies its use. That said, the implementation of the MISP must be conducted by trained staff using a coordinated approach (Women’s Refugee Commission, 2003).

- It is important that the MISP implementation include targeted programme interventions for adolescents and vulnerable sub-groups such as, orphans, separated adolescents, adolescent heads of household, marginalized adolescents, and children associated with armed forces and armed groups (UNFPA and Save the Children, 2009). MISP-targeted programme interventions for adolescents should include basic prevention activities, multi-sector coordination with adolescent participation and adolescent-friendly services (UNFPA and Save the Children, 2009).

- MISP implementation must also include targeted programme interventions for women and girls who are marginalized based on their sexual orientation, gender identity, age, ethnicity, or religion. For example, transgender women around the world are not only subject to sexual and physical assault because of their gender identify, they may also be refused services available to other women survivors (OHCHR, 2011).

- The following objectives and activities form the basis of the implementation process:

|

Objective |

Activities |

|

Identify an organisation(s) and individual(s) to facilitate the coordination and implementation of the MISP.

|

|

|

Prevent violence against women and girls and provide appropriate assistance to survivors. |

|

|

Reduce HIV transmission |

|

|

Prevent excess neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality |

|

|

Plan for the provision of comprehensive reproductive health services, integrated into primary healthcare |

|

Excerpted/Adapted from: IASC. 2005. “Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings,” pg. 63 & IRC. 2012. “GBV Emergency Response & Preparedness: Participant Handbook,” pgs. 46-47.

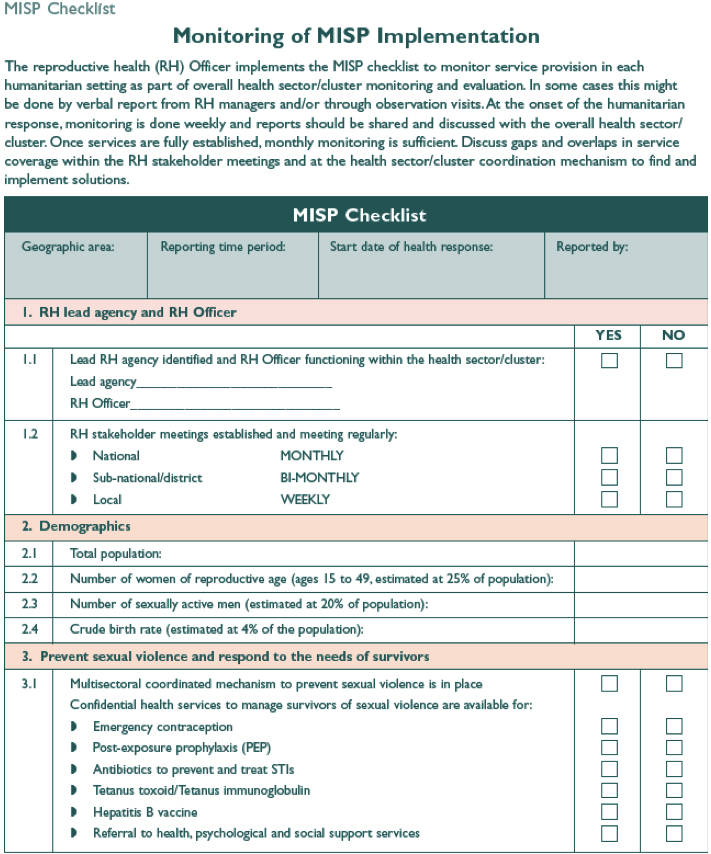

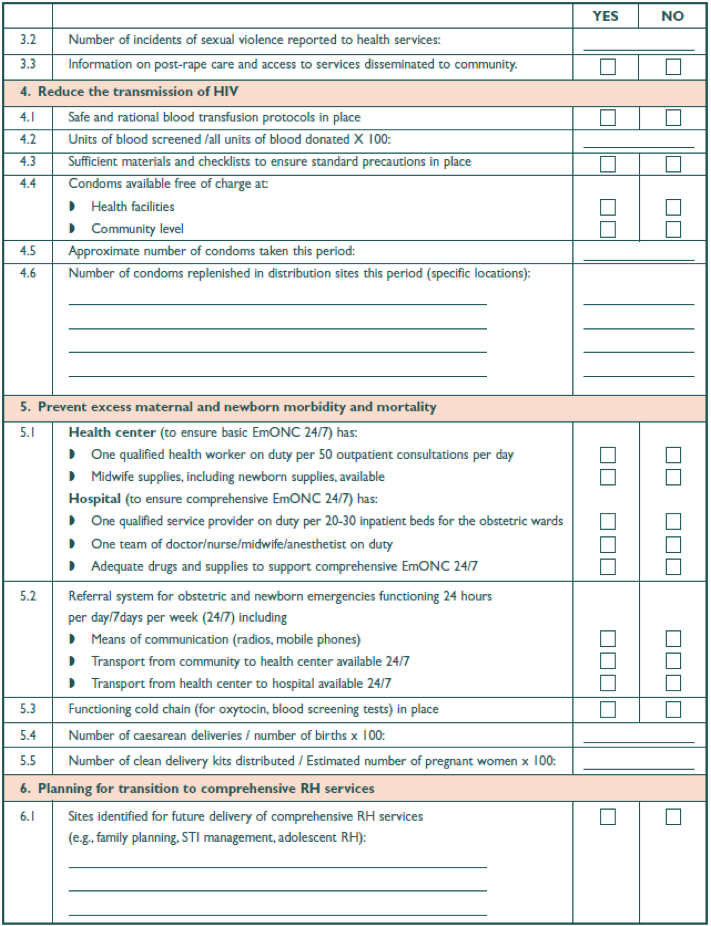

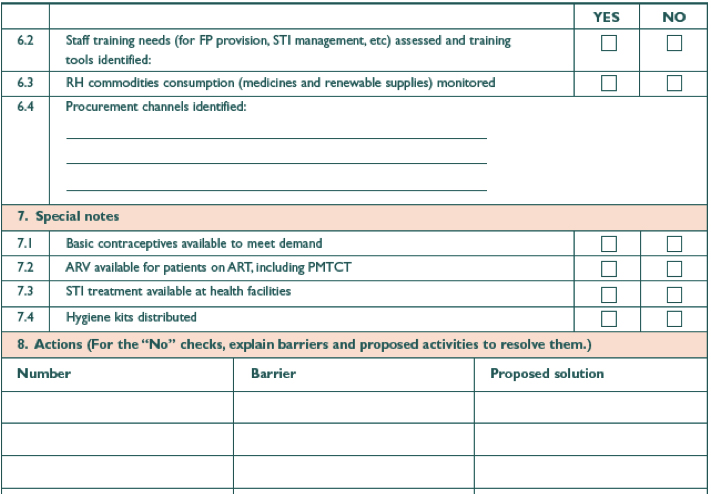

- Monitoring the implementation of the MISP is essential. Even if VAWG partners are not directly responsible for monitoring activities, they should be familiar with key monitoring components, summarized in the following tool:

Example: Clinic staff in North Darfur distributed emergency contraception (EC) to village midwives in addition to a flyer (in Arabic) developed by the MISP Coordinator on why and where women and girls can access care for rape. African Union (AU) commanders in North Darfur were informed by the MISP Coordinator to refer all rape survivors to a local clinic for treatment. The AU civilian police (CIVPOL) patrol also distributed information flyers (in Arabic) on the benefits and availability of care for survivors of sexual violence after an attack. In North Darfur, the MISP Coordinator conducted meetings with CIVPOL members about the importance of the clinical management of rape survivors. In West Darfur, midwives were identified as sexual violence protection focal points and internally displaced women could approach these focal points confidentially; the focal points referred women to receive medical care. In North Darfur, traditional birth attendants (TBAs) delivered messages on sexual violence to the community. In South Darfur, women’s health teams conducted community outreach to survivors of sexual violence. Some agencies immediately established women’s centers in camps which provide a safe place for women and girls and provide a space for survivors of sexual violence to receive confidential, holistic care in an environment that minimizes the social stigma.

Key strategies that made this programme so effective and could be adapted by other programs are:

- Information about emergency contraception was distributed by known healthcare providers in local language

- Police were engaged in referring rape survivors early

- Education about sexual violence and the care available was distributed by an authoritative staff

Different focal points were identified based on who was respected and accessible in the community

Source: Excerpted from the Women’s Commission field team from work conducted in 2005 to 2006. Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, 2006 in the Minimum Initial Services Package: A Distance Learning Module, revised 2011)

Additional Tools:

For comprehensive information on the MISP, see the Women’s Refugee Commission website.

See also case studies related to implementing the MISP.

For training material on the MISP, see: Women's Refugee Commission. 2006 (revised 2011). “Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for Reproductive Health in Crisis Situations: A Distance Learning Module.”

See the Emergency Toolkit for GBV Responders (International Rescue Committee). Available in multiple languages.

See UNFPA and Save the Children. 2009. “Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings,” MISP: Adolescent and Sexual Violence Fact Sheet.