- As with the MISP, clinical care for rape survivors should be available from the earliest onset of an emergency. It is the responsibility of health actors to ensure that health staff is trained and health facilities are equipped to provide care to survivors. This includes having a clinical management of rape protocol in place (IRC, 2012).

- It is the role of those working on VAWG to provide support to the health actors in sensitizing medical and non-medical personnel to the diverse needs of survivors, and promoting compassionate care. VAWG actors also facilitate coordination with health and other sectors to ensure survivors receive all needed services. VAWG actors without a medical background do not provide any direct health services, procure or dispense drugs, or supervise health staff (IRC, 2012).

- Health and VAWG actors should also work in concert to ensure that all actors on the ground are informed of existing national guidelines and protocols for the clinical management of rape, to ensure that all actors are providing appropriate health responses to survivors of rape (IRC, 2012).

|

Healthcare Providers |

|

GBV Workers |

|

|

|

|

Both healthcare & gbv actors |

||

|

||

Excerpted from IRC. 2012. “GBV Emergency Response & Preparedness: Participant Handbook,” pg.57.

- Key elements of health response for survivors of sexual violence include:

Excerpted from UNFPA. 2011. Managing Gender-based Violence in Emergencies: E-Learning Companion Guide, pg. 80.

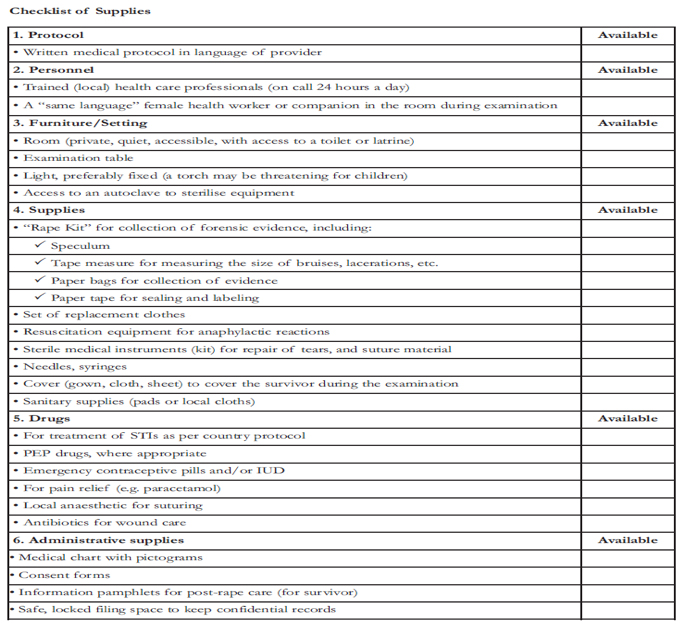

- Additional elements of clinical management are outlined below (adapted from WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR, 2004; IASC, 2005). All those working on VAWG should understand the basic process of an exam and the responsibilities of the health care provider. It should be noted that when designing clinical management programs in conflict and post-conflict settings it is necessary to adapt to each situation in the field, taking into account national policies and practices and availability of supplies, staff, and other resources.

1. Ensure preparations have been made

- Health care providers should be trained to provide comprehensive and compassionate care to all survivors, irrespective of age, class, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, gender identity, ability, religion, or other aspects of identity. Provide health care providers with sensitivity trainings around issues of diversity when possible.

- Priority should be given to training “same language” female health care providers.

- Health care facilities should have the necessary equipment and supplies in order to provide quality basic health care services, as identified in the checklist below.

Fuente: IASC, 2005, Guidelines for HIV/AIDS Interventions in Emergency Settings, p.82.

2. Prepare the survivor and read their history

- Introduce yourself and explain the basic procedures to be performed .

- Calm the survivor saying to him that it has the control over the examination and that he has a right to push back any aspect of the examination to which he(she) does not want to surrender. The survivor should be able to be rely on the presence of a person who should support him.

- Reading the history, keep a calm voice and let the survivor answer all the questions at their own pace , leaving enough time to gather all the information necessary time. Avoid repeating questions that have been asked and answered by others involved in the case.

- Explain that the test results are confidential. You need to obtain the informed written consent of the survivor, or their parents or guardians if it is a minor. However , remember that there is always the possibility that the offender is a parent or guardian.

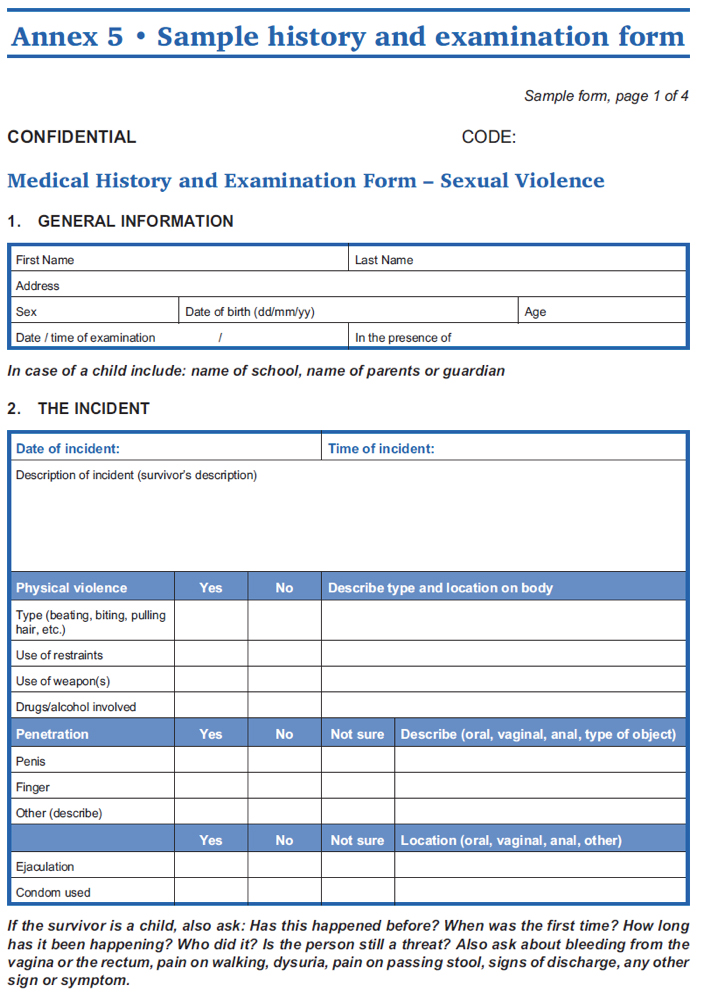

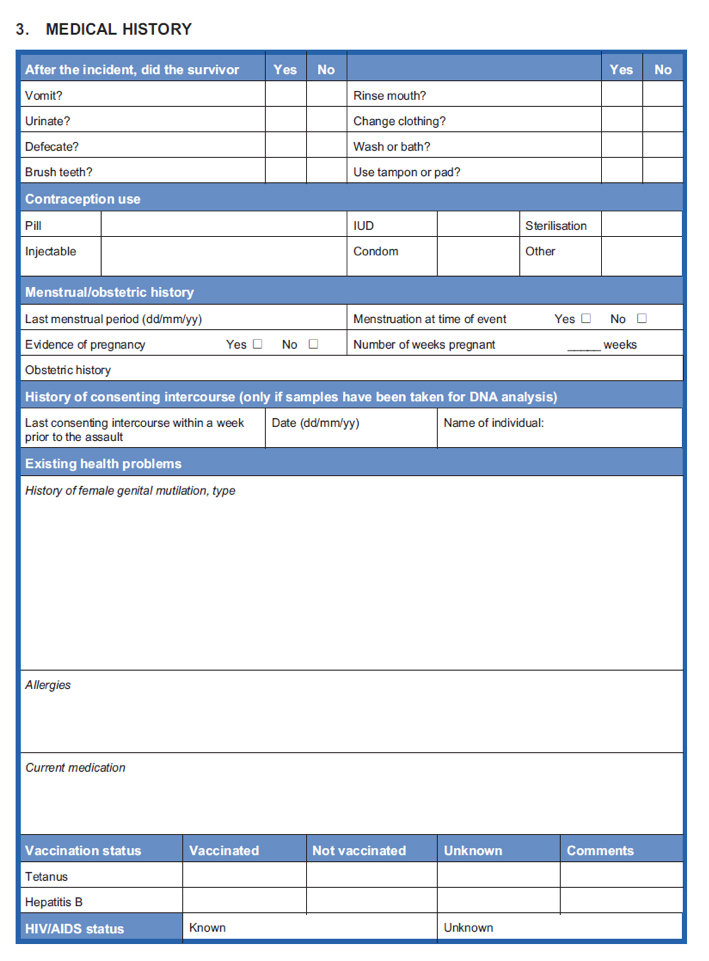

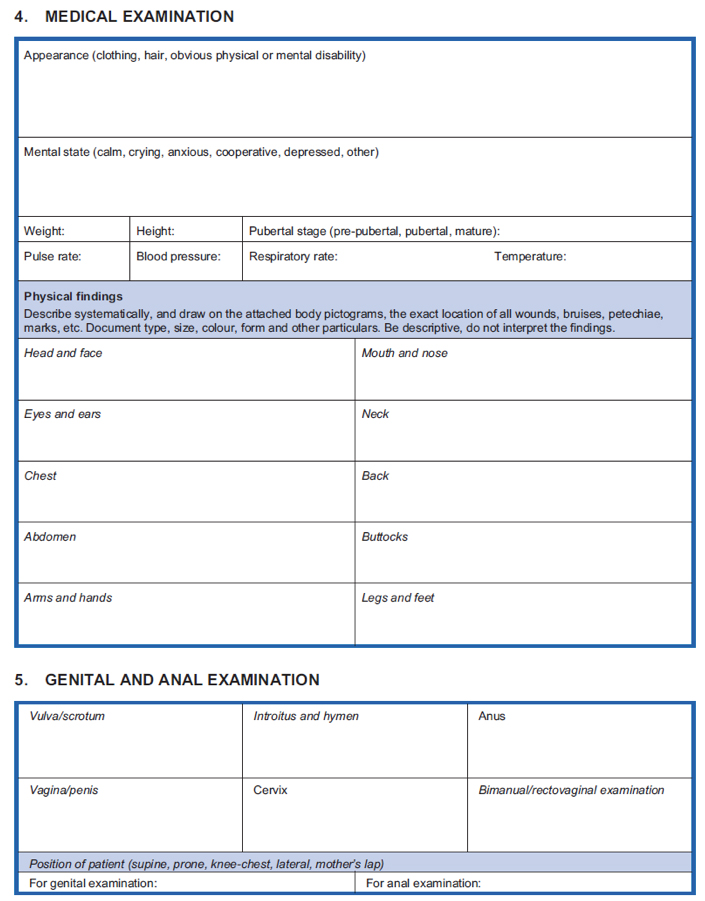

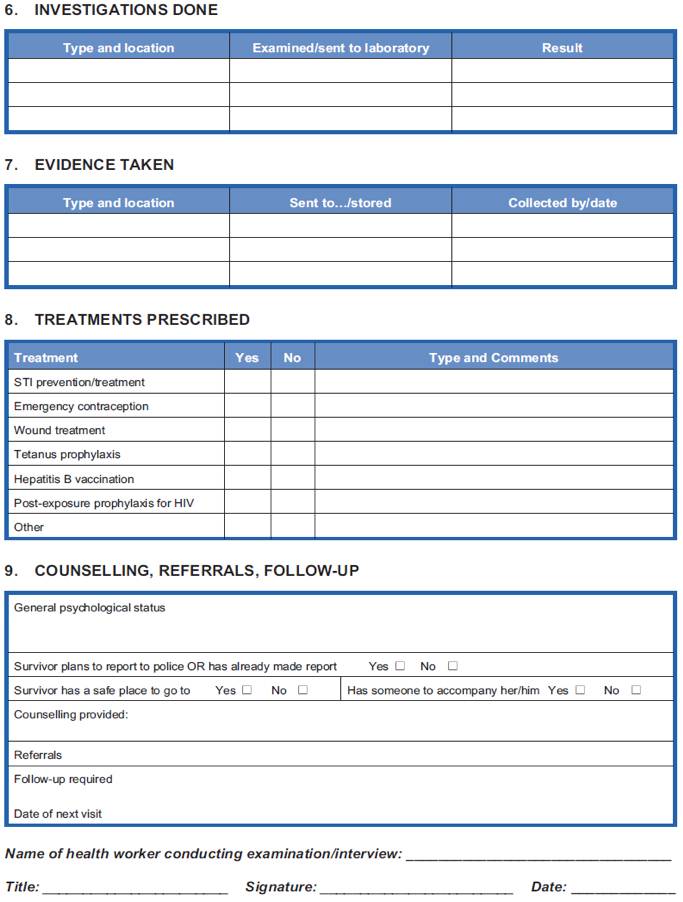

- For an example of a form of clinical history and physical examination can be used as a guide for the treatment of victims of violence against women and girls, see the next tool. (For more on the meeting related services on violence against women and girls information , see the collection of data on service provision.)

Source: WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR. 2004. “Clinical Management of Rape Survivors: Developing Protocols for use with Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons- Revised Edition,” pgs. 44-47.

3. Perform the examination

- At the time of the examination, explain to survivors that experiencing somatic symptoms of panic or anxiety (ex. dizziness, shortness of breath, palpitations etc) is common amongst people who are afraid after having experienced a traumatic event. Explain that these reactions are not due to disease or injury; rather, that they are part of experiencing strong emotions, and will go away over time when emotion becomes less.

- A medical examination should only be conducted after receiving consent and should be conducted in a compassionate, confidential, systematic, and complete manner, following an agreed upon protocol.

- Examinations should follow the guiding principles in providing health services to survivors. For more information see the Health Module.

4. Collect minimum forensic evidence

- Where possible, forensic evidence may be collected in order to assist the survivor in pursuing legal action.

- Local legal requirements and laboratory facilities determine if and what evidence should be collected. Do not collect evidence that cannot be processed or that will not be used.

- The collection of forensic evidence should be the choice of a survivor. Respect this choice and do not pressure in any way.

- For more information on collecting forensic evidence see the Health Module.

5. Provide compassionate and confidential treatment

- Treatment of life threatening complications and referral if appropriate.

- Make referrals, with survivor’s consent, to other services such as social and emotional support, security, shelter, etc.

- Discuss immediate safety issues and make a safety plan

- Prescribe relevant treatment in relation to how soon after the incident the survivor seeks treatment.

- Within 72hrs treatment should be prescribed for the following:

i. Prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

ii. Prevention of HIV Transmission

iii. Prevention of Pregnancy through emergency contraception

iv. Wound care

v. Prevention of Tetanus and Hepatitis B

vi. Mental health care

-

- After 72hrs treatment should be prescribed for the following:

i. STIs

ii. HIV Transmission

iii. Pregnancy

iv. Bruises, wounds and scars

v. Tetanus and Hepatitis B

vi. Mental health care

6. Counsel the survivor

- See Psychosocial section

7. Address follow-up care of the survivor

During the emergency phase of a humanitarian crisis it is possible that a survivor will not or cannot come back for a follow-up visit. As such, it is important to provide maximum input during the first visit.

See the Post-exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Infection Joint WHO/ILO Guidelines.

For additional information on how to provide follow-up care when the emergency phase permits, see “Clinical Management of Rape Survivors: Developing Protocols for use with Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons- Revised Edition” (WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR, 2004).

Example: In Hagadera Refugee Camp in Dadaab, Kenya, IRC implements health services. An assessment of health facility capacity to respond to survivors revealed many issues: no private setting, no trained staff, lack of supplies, and poor organization of service delivery. In tracing the survivor's route through this health facility, it was discovered that a survivor had to make six stops to receive care, causing threats to her confidentiality and privacy, and secondary traumatization at having to retell her story several times. The team in Dadaab, Kenya, created an action plan after this assessment. They trained all staff, both clinical and non-clinical, including the security guards, to protect patient confidentiality, increase awareness about sexual assault and improve attitudes towards survivors and increase technical knowledge of direct patient care. They also gathered all missing resources, including consent forms, supplies for the exam, and patient-information materials. They developed a referral database and appointment cards. Finally, they had a staff member and target date devoted to each piece of the plan, to ensure it was carried out. All resources were obtained and organized by integrating clinical and psychosocial services into one private center. The survivor no longer has to travel through many places within the hospital and receive care. She now receives all services in one private and confidential place. All resources are organized effectively within this center. Protocols are available and on display. A trained staff doctor is on-call. A private and safe room with necessary equipment is available 24 hours to receive survivors. Medicines and supplies are gathered in one place, so the patient is not traveling between different places in the health facility to receive tests or treatments. A locked filing cabinet for records is available so that the patient information is kept confidential. And finally, counseling is provided in the same center through IRC GBV, and a referral network for other psychosocial and legal services is defined and contacts are posted.

Source: Smith Transcript, Johns Hopkins Training Series, 2011.

- All clinical care providers must abide by the guiding principles of survivor-centered care. It is also important that providers understand and meet the needs of survivors with special needs:

-

- Elderly Women: Following menopause women experience decreased hormonal levels which result in reduced vaginal lubrication and a thinner more fragile vaginal wall. As such, elderly women who have experienced sexual violence in the form of vaginal rape have are especially at risk of vaginal tears and injury and the transmission of STIs and HIV. When examining this population, health providers should use a thin speculum for genital examination and if the only purpose of the examination is the collection of evidence or to screen for STIs, health care providers should consider inserting swabs only without the use of a speculum (adapted from: WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR. 2004).

- Transgender and intersex women: Women whose biological sex differs from their gender identity require different needs for medical care than most cisgendered women (women who identify with the sex/gender they were assigned at birth). Education and sensitization of health actors is essential in adequately meeting the needs of transgender and intersex women who have survived sexual assault (OHCHR, 2011; Grant et. al., 2011).

- Lesbian and bisexual women: It should not be assumed that all women are in heterosexual relationships. In addition, research from around the world indicates lesbian and bisexual women can be specifically targeted by men for rape (OHCHR, 2011). When providing health services to survivors, safe space should be provided for women to confidentially disclose same-sex relationships and possible bias-motivated crimes (OHCHR, 2011).

- Women with disabilities: Special consideration must be given to the specific health and medical needs of women with disabilities, as well as the physical accessibility of these services. Those with hearing or visual impairments must be provided with appropriate means of communication (Human Rights Watch, 2010).

- Children: When providing health services to child survivors of sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict humanitarian settings it is important to ensure a safe, caring and child-friendly environment. It is also important that health care providers modify the medical examination and medical treatments as necessary. Health care facilities should ensure that health care providers are familiar with child development and anatomy and are trained and comfortable treating child survivors. Health care providers should also be familiar with local referral networks and the procedures for communicating with child support agencies and other social services. It is also important that all those working in health care facilities with children survivors understand national child abuse laws as well as local police and court procedures (adapted from IRC, 2009).

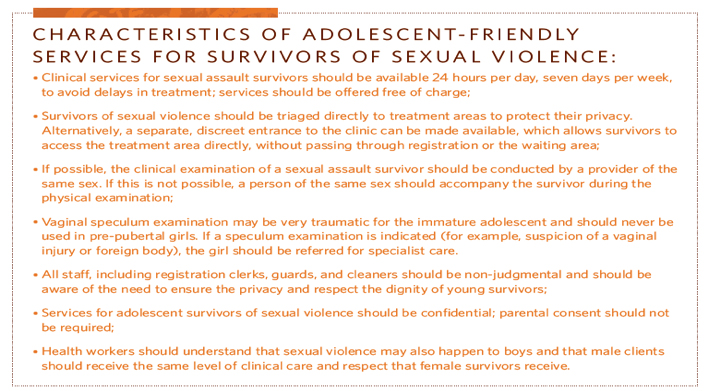

- Adolescents: Adolescent populations face an increased vulnerability to violence in conflict and post conflict settings. Adolescents may be coerced into providing sex in exchange for basic necessities such as food, shelter and security due to poverty, displacement and separation from their families and communities (UNFPA and Save the Children, 2009). Furthermore, unaccompanied adolescents as well as those who have the responsibility for caring for younger family members are at a heightened risk of sexual exploitation and abuse due to their dependence on others for survival and their limited decision making power and limited abilities to protect themselves (IASC, 2005 as cited by UNFPA and Save the Children, 2009). When providing health care services for adolescent survivors of violence against women and girls is important to modify services to address their special needs.

Excerpted from: UNFPA & Save the Children. 2009. “Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings,” MISP: Adolescent and Sexual Violence Fact Sheet, pg. 30.

Additional Tools

Clinical Management of Rape e-Learning Programme (UNHCR/UNFPA/WHO, 2010). Available in English and French. The course is a self-instructional, interactive e-learning programme based on the content of the WHO/UNHCR guidance on Clinical Management of Rape Survivors, and the training materials used by UNHCR and UNFPA in field-based face-to-face training sessions.

Clinical Care for Sexual Assault Survivors (IRC, 2009). The goal of this training tool is to improve the clinical care of sexual assault survivors in low resource settings by encouraging compassionate, competent, and confidential care in keeping with international standards. It is intended for all clinic workers who interact with sexual assault survivors, with a separate section specifically for non-medical staff.

Trainer's Manual on Clinical Care for Survivors of Sexual Violence (van Houten, Helen, and Keta Tom (eds.)/ Ministry of Health, Kenya, 2007). This manual is a resource for health care providers. The manual aims to support standardized management of post-rape care for survivors of violence. The guidance covers both medico-legal issues and post-rape services for a 3-day training that should be used in its entirety. The modules include forensic examination, specimen collection, analysis and documentation and clinical management, including basic counseling. Available in English; 89 pages.

GBV Emergency Response & Preparedness: Participant Handbook (IRC, 2012).

Caring for Survivors Training Pack (UNICEF, 2010). Available in English. This Training Pack can be used to develop multi-sectoral skills (e.g. health, psychosocial, legal/justice and security) and is designed for professional health care providers, as well as for members of the legal professionals, police, women’s groups and other concerned community members, such as community workers, teachers and religious workers. The training includes a facilitator guide for medical management of sexual assault.

Clinical Management of Rape Survivors: Developing Protocols for use with Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR. 2004). This guide includes detailed guidance on the clinical management of women, men and children who have been raped. It is intended for use by qualified health-care providers in developing protocols for the management of rape survivors in emergencies, taking into account available resources, materials, and drugs, and national policies and procedures. It can also be used in planning health-care services and training health-care providers.

Guidelines for medico-legal care of victims of sexual violence (World Health Organization, 2003). The aim of these guidelines is to improve professional health services for all individuals (women, men and children) who have been victims of sexual violence by providing: health care workers with the knowledge and skills that are necessary for the management of victims of sexual violence; standards for the provision of both health care and forensic services to victims of sexual violence; and guidance on the establishment of health and forensic services for victims of sexual violence.

For a collection and review of existing trainings for healthcare workers, see Gender-Based Violence Training Modules: A Collection and Review of Existing Materials for Training Health Workers (Murphy, C., Mahoney, C., Ellsberg, M. and Newman, C./The Capacity Project and USAID, 2006). Available in English.