Information on the rights and responsibilities of shelter residents is important to make available as part of the arrival process to clarify expectations related to women’s safety, participation and other aspects related to her stay at the shelter (e.g. the information that can be shared with non-residents; visitors guidelines or contact with abusers in cases of domestic violence, etc.).

Framing guidelines as rights and responsibilities rather than ‘rules and regulations’ aligns with the core principles of empowerment and self-determination, which should be integrated across all components of shelter services to ensure women’s rights are truly promoted by service providers.

Rights and responsibilities should be designed with flexibility and responsiveness to women’s needs and may complement or be part of the shelter policy.

They should describe the environment to be maintained at the shelter and should be posted or made easily accessible to residents. Key issues to be considered include:

- Safety and security (e.g. physical security of the facility; confidentiality of names, addresses and other information; and visitation)

- Use of shared and private spaces (e.g. housekeeping; maintenance of play areas for children; hours; respect of privacy; regulation of noise; and other house rules.)

- Interpersonal communication and behaviour between and among residents, their children, and staff (e.g. use of violence; respectful communication)

- Health (e.g. medical assistance; testing and disclosure related to communicable diseases, such as HIV; alcohol, cigarette and other substance use.)

- Opportunities for participation (house assembly, shelter council, support groups, workshops, training, committees, shared childcare schemes and meetings.)

- Other (e.g. responsibility for children; financial contributions; transition out of the shelter and re-entry; complaints processes; etc.) (Melbin et al., 2003).

Illustrative Example: Missouri Shelter Rules Project (United States)

In 2007, the Missouri Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence (MCADSV), a state-wide network of over 100 domestic and sexual violence programmes, began a project to review the approach to rules used by shelters in the Coalition. The intervention aimed to improve the effectiveness of services provided by shelters, and developed in response to recurring challenges experienced by advocates and shelter staff in implementing rules (for example, related to children, chores, confidentiality, conflict resolution, curfew, drug and alcohol use, kitchens and food, medications, mental illness, entering/exiting the shelter, and participation in support groups and house meetings). The project has also addressed the ongoing debate related to the need for rules and their alignment with shelter principles of empowerment and autonomy for women. During the pilot, an initial seven shelters chose to: remove written rules altogether (2 programmes); reduce the number of written rules in place (4 programmes); or improve policies and procedures for staff in place of written rules for residents (1 programme). After a year and a half, six shelters continued and seven new shelters joined the initiative. The Missouri experience demonstrates that minimal-rule approaches can maintain shelter structure and safety for survivors, while creating a more welcoming environment and providing more individualized services for women residents. This responds to survivor feedback on problematic rules as well as staff perspectives raised in defense of maintaining more comprehensive regulations (see Lyon, E., Lane, S. & Menard, A. 2008. “Meeting Survivors’ Needs: A Multi-State Study of Domestic Violence Shelter Experiences”. University of Connecticut School of Social Work and Anne Menard, National Resource Center on Domestic Violence).

Key lessons from the intervention include:

- Shelters should have the organizational capacity to support internal transformation when revisiting their approach to rules (e.g. strong leadership and commitment to fully engage staff, while managing disagreement and resistance to change that may occur during the process).

- An intervention to revise rules may not be appropriate in all settings, particularly if there is strong resistance throughout the team that cannot be changed through multiple dialogues and training.

- It is important to involve, from the beginning, both shelter administrators/ managers as well as advocates/staff in the process of change, as each group has a particular role and perspective on the function of rules, and buy-in from all groups is necessary to successfully implement change.

- Additional training and continuous opportunities for dialogue should be provided to all staff to reinforce the shelter’s values, approach to advocacy and service provision, as well as facilitate the process of change. Managers should be prepared to respond to staff changes, for instance, if staff members are unable to overcome their resistance to the intervention.

- Shelters may be more successful in transforming their use of rules when collaborating with other shelters or a coalition of shelters, or drawing upon the experience and support of others who have implemented similar changes.

- The process of transforming the environment within a shelter takes time and may not be easy for managers or staff. Evaluation of the process should be conducted well-after the intervention has begun, to provide sufficient time for staff to reflect on the process and its outcomes on their advocacy practices and women’s experiences.

- Physical changes to the shelter may facilitate the reduction of rules (e.g. creating separate sleeping or bathing spaces for women and their families; locked spaces for women to keep their food and belongings; safe areas for children to play without constant, direct supervision; security features to enable women to freely exit and enter the shelter, etc.). Despite initial costs, strategic investment in improving the living environment has long-term benefits on the effectiveness of the shelter and services provided by advocates.

- There are various approaches to supporting a minimal-rule environment, and each shelter should determine the most appropriate practices which meet the needs of its residents and enable staff to provide the most effective services.

The Missouri project experience is captured in the manual How the Earth Didn’t Fly Into the Sun: Missouri’s Project to Reduce Rules in Domestic Violence Shelters (Missouri Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2011), which also provides detailed guidance and templates for integrating a minimal-rule approach within a shelter.

Complaints Procedures:

Women should have opportunities to communicate any grievance or complaint they have with the staff or services being provided at the shelter. In addition to ongoing monitoring of services and mechanisms for receiving feedback from residents, a complaints process is important to enable shelters to address concerns of residents and improve the quality of its support.

A complaints process should cover a range of options available to ensure that women can raise their concerns in a manner in which they feel comfortable, and that problems are resolved using the most effective and appropriate methods (which may vary depending on the specific grievance).

Key considerations for establishing complaints procedures include:

- Determining an appropriate and realistic time frame for the shelter to address complaints.

- Identifying the different mechanisms which may be pursued by women to communicate and seek resolution for their complaints. These may involve:

- direct dialogue with relevant staff or their supervisor if the woman is unable or uncomfortable to speak with the staff involved;

- participation in a facilitated discussion or mediation on the issue;

- raising the issue in fora for shelter residents to discuss concerns or via representatives of residents, if such mechanisms exist; or

- providing confidential and anonymous written feedback, for example, through a locked complaints or comment box which is reviewed by shelter managers or a joint group of shelter staff and residents.

- filing a written complaint with the staff member, their supervisor or higher-level managers.

- Clarifying the chain of authority or levels through which complaints will be processed (e.g. supervisors, followed by shelter managers, executive director, and if needed, to the shelter’s board or governing body).

Women should be informed of the complaints procedures upon their arrival at the shelter as well as when a particular issue is raised. Written information should also be available to all residents in accessible formats (i.e. hard copies of material in communal areas, with specific versions in the different languages used by residents, and alternative formats designed for women with communication disabilities or limited literacy) (WSCADV; WAVE, 2004).

Tools:

Training Manual for Improving Quality Services for Victims of Domestic Violence (Women Against Violence Europe, 2008) offers training modules for shelter workers on understanding the problem of violence against, the role of shelters, how to set up a shelter, how it should be funded, what services should be offered, how to maintain a safe and secure shelter and information about the management of shelters, community life in shelters, public relations, networking and evaluation. Available in English.

Away from Violence: Guidelines for Setting Up and Running a Women's Refuge (Women Against Violence Europe, 2004). This briefing kit, developed by, is a resource for professionals intending to set up a shelter and may be used to support advocacy for improved policies and government support for shelters. The manual seeks to improve standards that may be applied across the various country-contexts in Europe and provides practical guidance on how to establish, organise, operate and manage a refuge (including the development of policies and procedures). Available in English (119 pages), Finnish, German, Hungarian, Italian, Portuguese, Greek, Estonian, Polish, Romanian, Slovak, Slovenian, Czech, Lithuanian, Serbo-Croatian and Turkish.

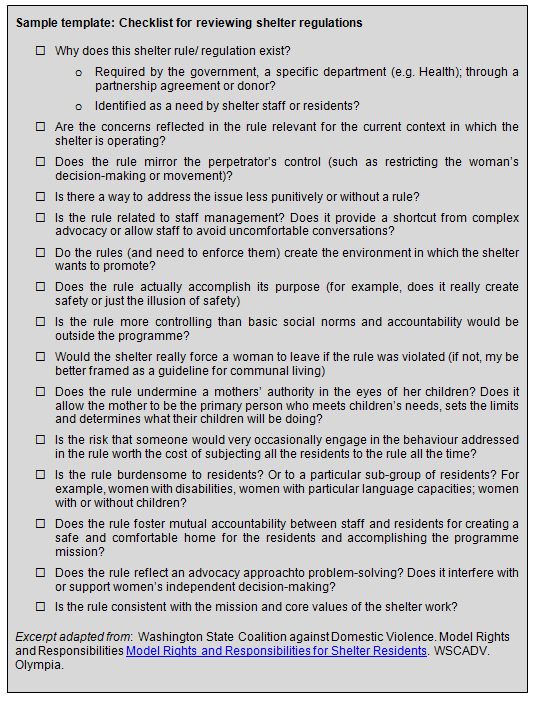

Model Rights and Responsibilities Model Rights and Responsibilities for Shelter Residents (Washington State Coalition against Domestic Violence). This model policy is for shelter managers and staff, based on the context in the United States. The resource provides guidance on the contents of shelter policies; a sample policy template that can be adapted as relevant; and a checklist of questions for reviewing existing shelter rules. Available in English.

Model Grievance Form (Washington State Coalition against Domestic Violence). This model form is for shelter managers and staff, based on the context in the United States. It includes a brief overview of issues to be considered in the grievance process and a sample letter which may be used or adapted by shelters. Available in English.

Shelter Rules (WSCADV). This online toolkit features audio visual materials, case studies, templates and other guidance to help shelter managers and staff understand and develop empowering guidelines for shelters that minimize control and maximize women’s autonomy. Available in English.

Combating violence against women: Minimum standards for support services (Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters, 2008). This resource summarizes the state of service provision for survivors of violence against women across Europe and identifies minimum standards of service delivery, including include qualified staff, child care services and provision for residents to stay as long as required, regardless of their financial situation. Available in English.

How the Earth Didn’t Fly Into the Sun: Missouri’s Project to Reduce Rules in Domestic Violence Shelters (Missouri Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2011). This manual provides guidance for integrating a minimal-rule approach within a shelter, with details on the experience of the Missouri Coalition Against Domestic Violence in the United States. The tool includes an overview of the Missouri project, as well as guidance for implementing changes in shelter rules, responding to challenges, and templates for resident and staff handbooks as well as surveys. Available in English.