“Be resilient when things go wrong: it is not just the problem, but how it is handled that makes or breaks a situation”. - WOMANKIND, 2008: Stop the Bus! I Want to Get On...

If conflict does occur, spending the time to analyze the source and nature of the conflict is important to effectively manage the situation. In crises that appear insurmountable, changing the alliance or the strategy can often offer solutions. This may include:

- Adjusting the campaign strategy in a way where the changes do not reduce the campaign’s chances to reach its goal.

- Growing the alliance, as the arrival of new members is likely to change the team dynamic; or

- Shrinking, splitting or dissolving the alliance as a painful option of last resort. If maintaining the alliance jeopardizes the campaign goal, this is a legitimate choice.

Ultimately, however, conflicts do yield useful insights and lessons. They need to be acknowledged and addressed in monitoring and evaluation processes so as to generate learning. Analyzing the likely causes and triggers of conflicts, and the ways in which the alliance has overcome them, generates vital learning for the alliance and future campaigns.

The following are some tools to analyze and mitigate conflict:

Any conflict of relationships and interests comprises three basic elements: the two parties to the conflict, and the issue at stake that is giving rise to the conflict. The two parties to the conflict normally hold contrary positions. They are each annoyed by the other actor; attempt to weaken the other’s position and to strengthen their own. Triangulation then aims to transform these positions into different interests. This takes place in three phases:

- We hold contrary positions. The other actor is the problem; he/she is inflexible and stubborn. We stick to our position, because we’re right.

- We focus on the issue at stake. We see the issue differently, and we recognize the fact that our interests are different.

- We study the issue in greater depth. We find that exchanging different perspectives and negotiating our interests leads to a compromise or a viable agreement.

A meeting where parties to the conflict can explain their points of view calmly and without interruptions (such as hostile questions) may help to situate the problem. Everyone involved in discussing the conflict should be encouraged to make a mental separation between their observations, feelings, needs and requests, and state these separately. It is important to appreciate everyone’s contribution to the discussion, even if opinions differ.

Source: adapted from GTZ, 2009.

Devising solutions

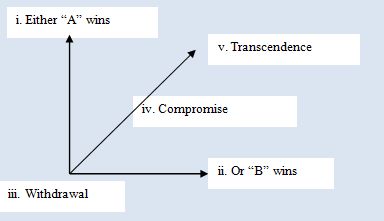

The conflict diagram, developed by peace and conflict scholar Johan Galtung (2000, Conflict Transformation by Peaceful Means: Participants’ Manual), can be a highly effective tool to explore the conflict parties’ positions and find “win-win” solutions as a group.

Practical Instructions: Conflict Diagram

If the conflict opposes two clearly diverging opinions, e.g. on the strategy to be adopted, a conflict diagram is a useful tool to explore alternatives.

Draw the diagram on a flip chart. The vertical and horizontal axes stand for the extreme positions of the parties “A” and “B” respectively. Explore potential solutions, e.g. brainstorm on different options and write them on cards. Then place the cards in the space in-between the axes. The diagonal line shows where the diverging interests can come together. In “withdrawal”, both parties end the cooperation; in “compromise”, each party gives up part of its position; in “transcendence”, both parties win.

External moderation

If many participants have a stake in the conflict or if the conflict cannot easily be solved internally, it may be useful to invite an experienced neutral facilitator for the meeting.

Tips for the moderator

The ability to act appropriately in conflict and in a manner that will be accepted by the participants presupposes an ability to both empathize and remain objective. We should ask ourselves the following questions:

What is going on here and what is at stake?

How do I obtain the information I need in order to gain a first overview?

What is my role? To what extent am I a participant in the conflict?

What do I need that I haven’t got in order to help transform the conflict?

Source: GTZ, 2009: 91.