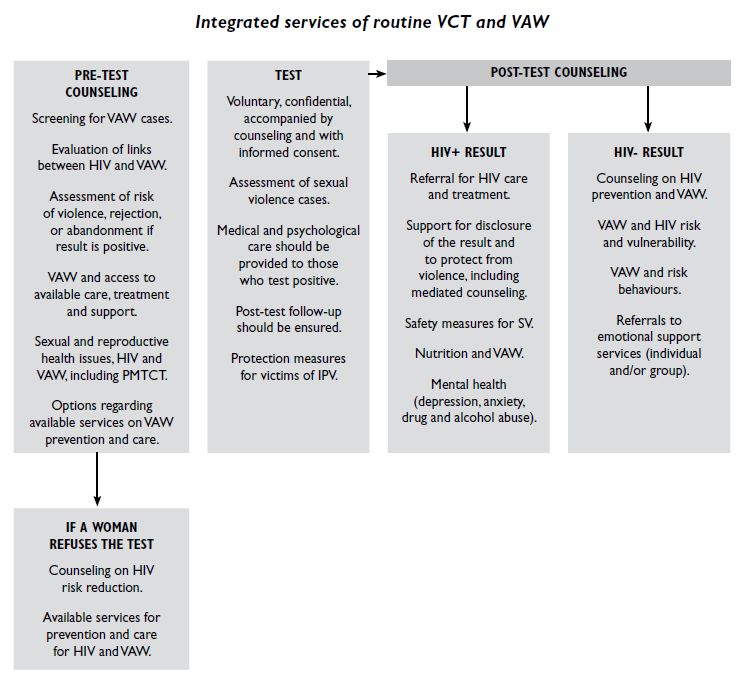

- The following provides a guide to integrating services of routine voluntary counselling and testing and violence against women and girls. This includes steps to take during pre-test counselling, testing, and post-test counselling.

Source: Luciano, 2009. Development Connections: A Manual for Integrating the Programmes and Services of HIV and VAW, pg. 41.

- Additional elements to consider when integrating violence against women and girls into voluntary counselling and testing services include:

- Screening: Given the scale and the many different forms of violence against women and girls, screening for such experiences during voluntary counselling and testing can help to provide women with an entry point to support and services (Luciano, 2009). Routinely asking women and girls about violence within voluntary counselling and testing settings can have additional benefits such as:

- Increasing the rates of disclosure

- Creating opportunities to reduce barriers to prevention care and treatment of HIV associated with violence against women and girls

- Changing service providers’ attitudes toward violence against women and girls

- Reducing stigma and discrimination related to HIV and violence against women and girls

- Screening: Given the scale and the many different forms of violence against women and girls, screening for such experiences during voluntary counselling and testing can help to provide women with an entry point to support and services (Luciano, 2009). Routinely asking women and girls about violence within voluntary counselling and testing settings can have additional benefits such as:

- Pretest Information or counselling: Providing pretest information and/or counselling gives health care providers an opportunity to share basic information about violence against women and girls and HIV/AIDS. This step also provides women with the opportunity to “assess their risk, think about risk reduction, and prepare themselves for the test results” (WHO, 2009a, pg. 31).

- Confidentiality: Tests must always be voluntary and confidential. Testing positive for HIV, or simply getting tested, may increase a woman or girl’s risk of violence. This is especially the case in situations where intimate partner violence is present. Therefore it is important to ensure that a partner will not find out about a woman’s decision to get tested unless the woman provides clear consent.

- Disclosure: Disclosure can result in violence and discrimination from intimate partners, family members and the community. For this reason it is important to ensure policies are in place to make disclosure voluntary.

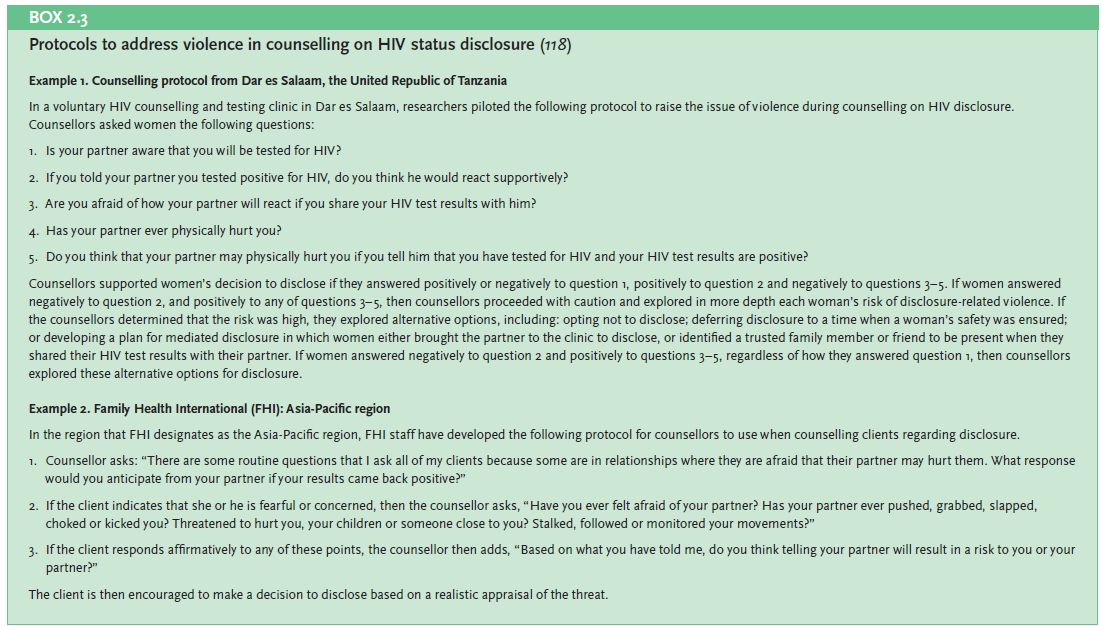

- When dealing with clients who experience intimate partner violence it is especially important to develop safe disclosure plans as part of the post-test counselling component of voluntary counselling and testing services. This should include:

- Engaging in a discussion with clients about their fears of violence and abandonment as factors in their decision to disclose their status to their partner (WHO, 2009a).

- Working with your client to develop the safe disclosure plan. When doing so it is important to recognize that where intimate partner violence is already present, disclosure can lead to increased violence.

- If your client agrees, consider mediated disclosure with the help of counsellor (Maman et al., 2006; WHO, 2006). By having a counsellor present, mediated disclosure creates a safe environment for disclosure. When conducting a mediated disclosure avoid blame and tension by providing accurate information about transmission and prevention (Baty, 2008).

- Encourage and support communication within couples about HIV/AIDS and voluntary counselling and testing. This can facilitate couples getting tested together and disclosing ones status (Maman et al., 2006; WHO, 2006). Meeting separately with men and women for pre-test and post-test counselling can help ease the process of couples voluntary counselling and testing, while helping avoid violence as well. After testing, give couples the option to come in together for serodisclosure, this option should be given with support clubs in place for sero-discordant couples (Maman et al., 2006).

Source: WHO, 2009a. Integrating Gender into HIV/AIDS Programmes in the Health Sector: Tool to Improve Responsiveness to Women’s Needs. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, Department of Gender, Women and Health, pg. 38.

- Routine Testing: Though there is a limited evidence-base on routine testing with varied opinions by practitioners and experts alike, routine testing can result in a violation of women and girls’ human rights, if it is not based on individualized informed consent. This implies that unless safety, confidentiality and choice are ensured, the Opt-in model should be used instead of the Opt-out model.

- The Opt-out model: This is when women are tested for HIV routinely, and have to clearly refuse testing if they do not want to be tested (World Health Organization and UNAIDS, 2007). Informed choice may be compromised when using this model because of lack of training of health providers and other barriers between health care providers and women such as class or cultural differences.

- The Opt-in model: This is when there is individualized informed consent instead of routine testing (World Health Organization and UNAIDS, 2007). Using this model is more appropriate when working with highly vulnerable populations who are especially vulnerable to increased violence when disclosing their HIV test results.

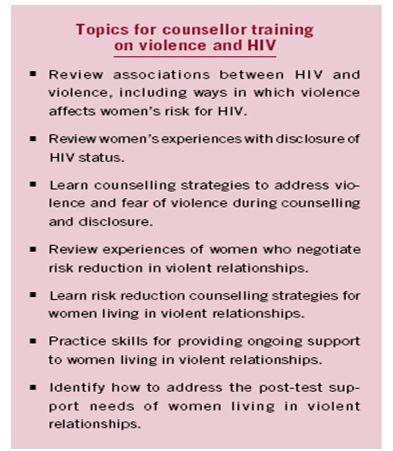

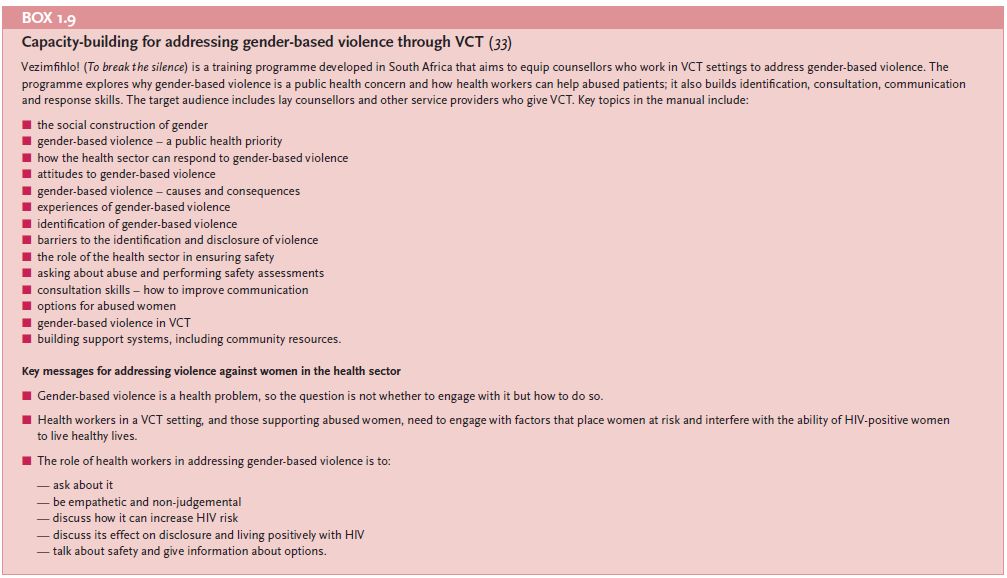

- Staff Training: Sensitivity trainings should be provided to voluntary counselling and testing staff to raise awareness on gender, class, and ethnic differences which can create power inequalities between themselves and clients (WHO, 2009a).This includes training on how to use simple language to explain medical and technical terms that clients may not otherwise understand and trainings on how to avoid expressing judgmental attitudes and personal biases towards clients (WHO, 2009a).

Source: Maman, S., King, E., Amin, A., Garica-Moreno, C., Higgins, D. and Okero, A., 2006. Addressing Violence against Women in HIV Testing and Counselling: A Meeting Report. Geneva, Switzerland. WHO, pg. 23.

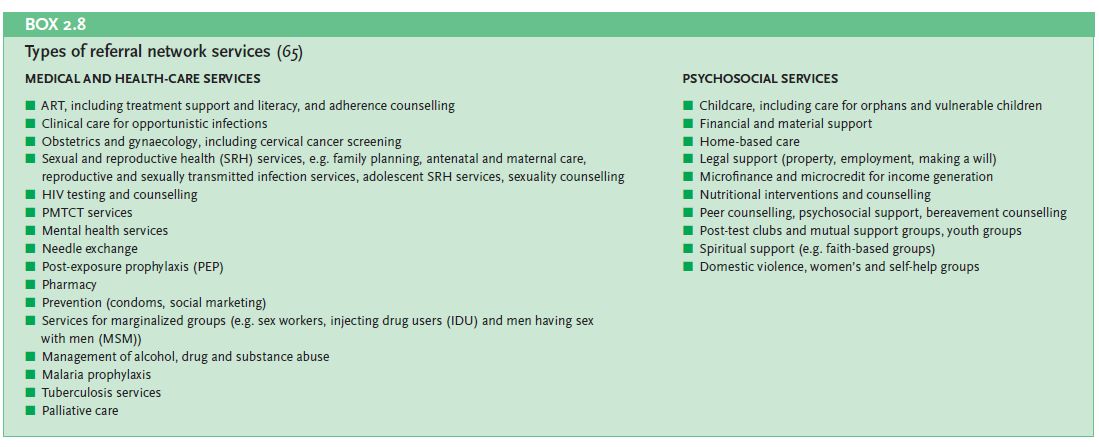

Referral services: The lack of available referral services for addressing violence makes it challenging for HIV programme staff to address violence against women and girls (WHO, 2009a). The following provides a comprehensive list of medical and health-care services as well as psychosocial services which should be included when building referral services for the integration of HIV/AIDS and violence against women and girls. In context were formal psychosocial support is weak, peer support programmes can be an important mechanism to support women through the HIV testing and counselling process(WHO, 2006).

Source: WHO, 2009a. Integrating Gender into HIV/AIDS Programmes in the Health Sector: Tool to Improve Responsiveness to Women’s Needs. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, Department of Gender, Women and Health, pg. 47.

Illustrative Tools:

Integrating HIV Voluntary Counselling and Testing Services into Reproductive Health Settings: Stepwise Guidelines for Programme Planners, Managers and Service Providers (IPPF South Asia Regional Office and UNFPA, 2004). Available in English.

Disclosure Assessment, by Suzanne Maman, is a 5-question tool to identify VAW victims and to assess their risk.

Risk Reduction Counselling for Women at Risk for Violence, by Elizabeth King, is a tool to raise the potential for violence in risk reduction counselling. The tool presents various role play scenarios that counsellors can use with clients to facilitate discussion about condom use and sexual coercion. It has 3 sections, as follows: 1) Younger couples and those in relationships, but not married; 2) Married couples; 3) Women involved in relationships (both permanent partnerships and married spouses).

Guidelines for Integrating Domestic Violence Screening into HIV Counselling, Testing, Referral & Partner Notification, by the New York State Department of Health, is a document outlining the New York State Department of Health’s guidelines on addressing violence against women and girls within HIV services. It includes such subheadings as: Domestic Violence Risk Assessment as a Standard of Care; Introducing a Discussion of Domestic Violence Within HIV Counselling and Testing; Referrals Should be Provided Whenever Domestic Violence or Risk of Domestic Violence is Identified; Discussion of Domestic Violence is Encouraged in Pretest Counselling; and Domestic Violence Screening is Required During Post-test Counselling of HIV-Infected Individuals. Available in English.

Counselling Guidelines on Domestic Violence Southern African AIDS Training Programme (Southern African AIDS Training Programme, 2001). Available in English.

VCT Counsellor Interview Guide (Raising Voices, 2008). As part of the SASA! Initiative, this tool was developed to provide practical guidance to voluntary counselling and testing counsellors about discussing violence with their clients. Available in English.

Additional Resources:

The Intersection of HIV and Intimate Partner Violence: Considerations, Concerns, and Policy Implications (Baty, M.L., 2008). Family Violence Prevention & Health Practice. Available in English.

Screening Persons Newly Diagnosed with HIV/AIDS for Risk of Intimate Partner Violence: Early Progress in Changing Practice (Klein, S.J., Tesoriero, J.M., Leung, S.Y., Heavner, K.K., Birkhead, G.S., 2008). Available in English.

Addressing Violence against Women in HIV Testing and Counseling: A Meeting Report (Maman, S., King, E., Amin, A., Garcia-Moreno, C., Higgins, D. and Okero, A./WHO, 2006). Available in English.