- According to the Palermo Protocol, trafficking means: “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs” (United Nations 2000, Art. 3).

- Involuntary servitude is the essential feature of trafficking. In 2010 over 12 million people around the world are estimated to be trafficked. (US Dept of State, 2010). The most common form of human trafficking is sexual exploitation, and the majority of victims of sexual exploitation are women and girls (UNODC, 2009).

- As each trafficking incident unfolds, the victim experiences threats to her physical and metal health. From the pre-departure stage, to the travel, transit and destination stages, through to detention, deportation and integration or return and reintegration, women and girls may experience repeated physical, sexual and psychological abuse or torture.

- Policies and protocols should assume health risks for trafficked women. Although trafficked women and girls could present at any type of service, including emergency rooms, the high health risks that they face mean that it is essential to provide information, counselling, and services.

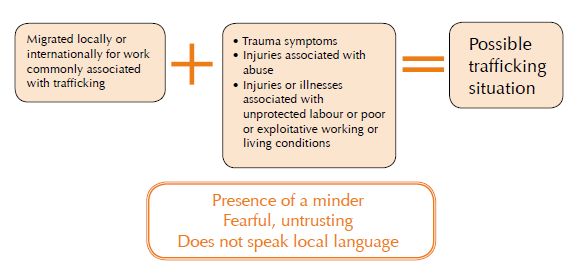

- As increased attention to ending trafficking and supporting victims of trafficking occurs through government and NGO programs, health providers will come into increased contact with trafficked women and girls. Health care providers should know the clues for identifying whether a person has been trafficked:

Source: excerpted from UN.GIFT (United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Trafficking), IOM (International Organization for Migration) and the London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 2009. Caring for Trafficked Persons: Guidance for Health Providers.

- Many trafficked women and girls are under such tight controls that they have no access to health care, despite the serious health risks they are subject to. When health personnel do come into contact with them, trafficked women and girls may be reluctant to disclose their situation for fear of prosecution (where sex work is illegal) or of deportation, since they are often in the receiving country illegally (Amnesty International, 2006). Health care providers should be especially aware of security risks that trafficked women face, and should attempt to interview women privately in a secure, soundproof room. Even if the provider does not speak the language of the client, translation should not be conducted by any person(s) accompanying the client.

- In all cases, the health providers’ main task to provide all required care and counselling according to the same guidelines and procedures as for all women affected by violence, but with special attention to safety assessment and safety planning, as well strict confidentiality.

- Health care providers should also abide by the following principles when engaging with trafficked women:

1. Adhere to existing recommendations in the WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women (Available in Armenian, Bosnian, Croatian, English, Japanese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish and Serbian)

2. Treat all contact with trafficked persons as a potential step towards improving their health. Each encounter with a trafficked person can have positive or negative effects on their health and well-being.

3. Prioritize the safety of trafficked persons, self and staff by assessing risks and making consultative and well-informed decisions. Be aware of the safety concerns of trafficked persons and potential dangers to them or their family members.

4. Provide respectful, equitable care that does not discriminate based on gender, age, social class, religion, race or ethnicity. Health care should respect the rights and dignity of those who are vulnerable, particularly women, children, the poor and minorities.

5. Be prepared with referral information and contact details for trusted support persons for a range of assistance, including shelter, social services, counseling, legal advocacy and law enforcement. If providing information to persons who are suspected or known victims who may still be in contact with traffickers, this must be done discretely, e.g., with small pieces of paper that can be hidden.

6. Collaborate with other support services to implement prevention activities and response strategies that are cooperative and appropriate to the differing needs of trafficked persons.

7. Ensure the confidentiality and privacy of trafficked persons and their families. Put measures into place to make sure all communications with and about trafficked persons are dealt with confidentially and that each trafficked person is assured that his or her privacy will be respected.

8. Provide information in a way that each trafficked person can understand. Communicate care plans, purposes and procedures with linguistically and age-appropriate descriptions, taking the time necessary to be sure that each individual understands what is being said and has the opportunity to ask questions. This is an essential step prior to requesting informed consent.

9. Obtain voluntary, informed consent. Before sharing or transferring information about patients, and before beginning procedures to diagnose, treat or make referrals, it is necessary to obtain the patient’s voluntary informed consent. If an individual agrees that information about them or others may be shared, provide only that which is necessary to assist the individual (e.g., when making a referral to another service) or to assist others (e.g., other trafficked persons).

10. Respect the rights, choices, and dignity of each individual by:

- Conducting interviews in private settings.

- Offering the patient the option of interacting with male or female staff or interpreters. For interviews and clinical examinations of trafficked women and girls, it is of particular importance to make certain female staff and interpreters are available.

- Maintaining a non-judgmental and sympathetic manner and showing respect for and acceptance of each individual and his or her culture and situation.

- Showing patience. Do not press for information if individuals do not appear ready or willing to speak about their situation or experience.

- Asking only relevant questions that are necessary for the assistance being provided. Do not ask questions out of simple curiosity, e.g., about the person’s virginity, money paid or earned, etc.

- Avoiding repeated requests for the same information through multiple interviews. When possible, ask for the individual’s consent to transfer necessary information to other key service providers.

- Do not offer access to media, journalists or others seeking interviews with trafficked persons without their express permission. Do not coerce individuals to participate. Individuals in ‘fragile’ health conditions or risky circumstances should be warned against participating.

11. Avoid calling authorities, such as police or immigration services, unless given the consent of the trafficked person. Trafficked persons may have well-founded reasons to avoid authorities. Attempts should be made to discuss viable options and gain consent for actions.14

12. Maintain all information about trafficked persons in secure facilities. Data and case files on trafficked persons should be coded whenever possible and kept in locked files. Electronic information should be protected by passwords.

Source: IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2006. Breaking the Cycle of Vulnerability: Responding to the Health Needs of Trafficked Women in East and Southern Africa.

Illustrative Tools:

The UN.GIFT (United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking) website has a full array of basic references, manuals and tools, and news about past and upcoming meetings on trafficking. The link relating to “best practices” is particularly useful as guidance.

Caring for Trafficked Persons: Guidance for Health Providers (United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Trafficking), IOM (International Organization for Migration) and the London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2009). Provides practical, non-clinical advice to help health providers understand trafficking, recognize associated health problems, and consider safe and appropriate approaches to providing healthcare for trafficked persons. The guidance is also useful for meeting the health needs of women migrant workers who are victims of abuse. The “action sheets” include: sexual and reproductive health, special considerations when examining children and adolescents, trauma-informed care, safe referral, mental health care, disabilities, and medico-legal considerations. Available in English.

WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women (Zimmerman, C. and Watts, C. 2003). Available in Armenian, Bosnian, Croatian, English, Japanese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish and Serbian)

Handbook on Direct Assistance for Victims of Trafficking (International Organization for Migration, 2007). Available in English.

Breaking the Cycle of Vulnerability: Responding to the Health Needs of Trafficked Women in East and Southern Africa (International Organization for Migration, 2006). Available in English.

Manual for Medical Officers Dealing with Child Victims of Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation (Manual for Medical Officers Dealing with Medico-Legal Cases of Victims of Trafficking for Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Child Sexual Abuse (United Nations Children’s Fund and the Department of Women and Child Development, Government of India, New Delhi, 2005). Available in English.

National Referral Mechanisms: Joining Efforts to Protect the Rights of Trafficked Persons: A Practical Handbook (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, 2004). Available in Albanian, English, French, Russian, Spanish, and Turkish.

For additional resources on trafficking, search the tools database.