- While there is no global standard for defining adolescence, it generally describes the transitional period from childhood to adulthood that begins at puberty, and is often characterized as the beginning and end of teenage years (ages 13-19), but can also be considered to begin as young as 10 years of age.

- Girls are at risk of multiple forms of violence during these years, including:

|

Son Preference |

In various cultures around the world, parents welcome the birth of sons, and are disappointed with the birth of daughters. At its most extreme, son preference can result in practices such as sex-selective abortion of female foetuses and female infanticide which, in some parts of South Asia, West Asia and China, have significantly altered usual female-to-male birth ratios (Plan International, 2007). In other cases, son preference is demonstrated in terms of gross neglect of girls, with sometimes fatal results (ECOSOC, 2002). Sometimes girl-child mortality is the outcome of discrimination against mothers. In settings where mothers do not receive adequate care and nutrition, their children, and especially their girl children, are at increased risk (Plan International, 2007). The most common manifestation of son preference, however, involves favouring the social, intellectual and physical development of a boy child over that of a girl child. Examples relevant to adolescent girls include requiring a daughter to quit school in order to take care of household chores, or preventing her from engaging in games and other activities with her peers so she can stay home and supervise younger siblings. |

|

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting |

Female genital mutilation/cutting, which involves the medically unwarranted excision of all or part of the external female genitalia, is primarily practiced in Africa, most prevalently in Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Sierra Leone, Somalia and northern Sudan (Toubia, 1999; Carr, 1997). Females typically undergo the practice between the ages of four and 14 (WHO, 1998). The extensive health risks associated with FGM have historically not been sufficient to halt the practice in many settings where social norms are used to dictate women’s sexuality. In many settings, FGM increases a girl’s prospects for marriage and may, in fact, be a prerequisite. In some traditional Islamic cultures, and despite the increasing number of imams who are speaking out against the practice, FGM may be considered by men and women alike to be ‘sunnah’, or required practice (Carr, 1997). Across the wide range of cultural, ethnic and religious groups that perform FGM, a shared trait in the perpetuation of the practice is the conditioning of families to accept and defend it. Various myths, such as the one insisting that FGM promotes cleanliness and good health, are used to stigmatise girls who have not been cut. Against this backdrop of social pressure, FGM continues to thrive, even in many settings where governments have outlawed it. |

|

Child Marriage |

Early marriage is defined by the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices as “any marriage carried out below the age of 18 years, before the girl is physically, physiologically, and psychologically ready to shoulder the responsibilities for marriage and childbearing.” (Inter-African Committee, 1993, in Somerset, 2000) This practice is most prevalent in developing countries. In South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, for example, it has been estimated that on average one in every three girls between the ages of 15 and 19 is already married, and in specific countries the percentages are much higher (Otoo-Oyortey and Pobi, 2003). As with the practice of FGM, the desire to control women’s sexuality may be one of the most significant reasons families choose to marry their daughters off at a young age. The practice may be promoted, for example, as a way of reducing a girl’s risk of engaging in premarital sex, or as way of maximising her reproductive lifespan. Amongst some African communities, a girl’s parents can obtain a higher bride price for a daughter who is a virgin, and therefore perceived to be free from HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. In Asian settings where dowry practices predominate, parents of a girl who is married off young may be able to pay less to the groom’s family because younger girls are considered more desirable than their older counterparts. Whatever the material or other benefits to the family, the consequences of child marriage can be deadly for a girl. Complications from early pregnancy, for example, are a leading cause of death for 15- to 19-year-old girls worldwide (black, 2001). If not fatal, early childbearing significantly increases girls’ risk for injuries, infections and disabilities, including obstetric fistula. Early childbearing can also pose risks to the girl’s child: A baby’s chance of dying in its first year of life is 60 percent higher if its mother is under, rather than over, the age of 18 (Black, 2001). Because of biological factors, young wives are also more physically vulnerable than mature women to contracting sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, from an infected partner—a danger compounded by the fact that girls are even less likely to be able to negotiate safe sex with their partners than are older women. |

|

Intimate Partner Violence |

One important risk factor for intimate-partner violence may be the young age of the wife: Research suggests that girls who are married early are at greater risk of violence than those who marry late, especially when the age discrepancy between the girl and her husband is significant (Rubeihat, cited in Black, 2001). Girls who are forced into marriage—exemplified to the extreme in ‘abduction marriages’ customary in certain parts of Africa, Eastern Europe and Asia—also typically suffer the added trauma of forced sexual initiation. Girls are also more likely to be socially isolated by virtue of their age and lack of independent resources, and therefore less likely to be able to seek assistance for domestic violence. Girls may additionally be more likely to accept the abuse by their partner as part of the power differential in their marriage (Otoo-Oyortey and Pobi, 2003). Young women in many parts of the world also experience dating violence, including controlling behaviours by boyfriends, verbal and physical abuse, and date rape. |

|

Incest |

Incest refers to any sexual activity between a child and a closely related family member. Although most cultures around the world have legal and social sanctions prohibiting incest, the problem is nevertheless widespread. The WHO estimates that of 150 million girls and 73 million boys worldwide who have experienced forced sexual intercourse, up to 56 percent of girl victims were abused by family members, compared with up to 25 percent of boy victims (UN Study on Violence Against Children, 2006). The peak age of vulnerability to child sexual abuse—whether within the family or committed by someone outside the family—is estimated to be between seven and 13 years of age (Finkelhor, 1994). Cross-culturally, evidence suggests that from 40 percent to 60 percent of sexual abuse in families involves girls under the age of 15 (Kapoor, 2000). |

|

Sexual Violence in Schools |

While data on girls’ exposure to sexual violence in schools is still limited, existing evidence paints a grim picture: In research undertaken in public schools in the United States, for example, 83 percent of girls surveyed in grades 8 through 11 reported exposure to some form of harassment (Newton, 2001). In many instances, the perpetrators are those who are entrusted with girls’ care and protection. Studies from Botswana, Ghana, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Pakistan indicate that teachers as well as male students expose girls to sexually explicit language and/or sexual propositions (Dunne, Humphreys and Leach, 2003; UNICEF and Save the Children, 2005). And the threat to girls is not only limited to the school grounds: Research from Peru found that a girl’s risk of sexual violence increases in relation to the distance she must travel to get to school (UN Study on Violence Against Children, 2006). This situation is exacerbated in school settings where there are few female teachers, especially in positions of authority. In many developing countries around the world, male teachers far outnumber female teachers. Such male-dominated contexts make it difficult for girls to challenge male authority and/or seek assistance. As such, girl students are likely to be exposed to violence both because of and as a method for reinforcing their lower status in relation to boys and to their male teachers. With regard to the former, boys can often bully, harass and even assault girls with relative impunity because girls have little recourse to protection in male-dominated school settings. With regard to the latter, boys may target girls who breach traditional norms of female subservience, such as those who are student leaders and/or are performing well in school, in order to ‘put them in their place’. |

|

Sexual Violence in the Community |

Given vulnerabilities associated with their age, physicality and lack of negotiating power, it is likely that adolescent girls are among the highest of all risk groups for sexual violence perpetrated against them by members of their community. However, for many girls around the world, sexual aggression by boys and men is normative, and therefore not perceived by girls (or boys) as criminal unless it crosses the bounds into more conformist definitions of rape. Notably, 11 percent of adolescents responding to a survey conducted in South Africa reported being raped, but a further 72 percent reported being subject to forced sex. (Jewkes et al., 2000, in Bennett, Manderson and Ashbury, 2002). Average estimates of coerced first sex among adolescent girls around the world range from 10 percent to 30 percent, but in some settings, such as Korea, Cameroon and Peru, the number is closer to 40 percent. Research from the Caribbean suggests that forced first intercourse there is as high as 48 percent (Koenig et al., 2004, Jejeeboy and Bott, 2003, Ellsberg and Heise, 2006). Importantly, younger adolescent girls appear to be most at risk, as the likelihood of sexual initiation being coerced or forced decreases as girls get older. Multi-country research conducted by the WHO found that women who reported (retrospectively) that their first sexual experience was before the age of 15 were more likely to have been forced or coerced than those who reported initiation before the age of 17 years. Those who reported sexual initiation after 17 years of age were the least likely of all women surveyed to report that it was forced (UN Study on Violence Against Children, 2006). |

|

Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation of Girls |

According to UNICEF, the majority of the estimated one million children who are forced or coerced into the sex trade each year are girls (UNICEF, 2005). Many of these girls are victims of global trafficking networks. While the highest numbers of prostituted children—some as young as 10 years of age—are thought to be concentrated in Brazil, India, Thailand, China and the United States, experts agree that child prostitution is a worldwide phenomenon that is not only on the rise, but ensnares increasingly younger girls (Willis and Levy, 2000). Although much more difficult to measure, a significant amount of sexual exploitation of children occurs outside the context of commercial markets. Children may engage in ‘survival’ sex for subsistence money or goods, or be taken in by ‘sugar daddies’, or older men who offer them presents, school fees, etc. in exchange for sexual favours. Emerging data suggests that the growing number of AIDS orphans in sub-Saharan Africa are at special risk: 47 percent of surveyed children in Zambia who were selling sex for money had lost both their father and mother to AIDS, and 24 percent had lost one parent (UN Study on Violence Against Children, 2006). Whether in commercial or non-commercial markets, children who are poor, uneducated, homeless, or for other reasons exist in society’s blind spot are those at greatest risk of being sexually exploited—and those least likely to receive assistance. |

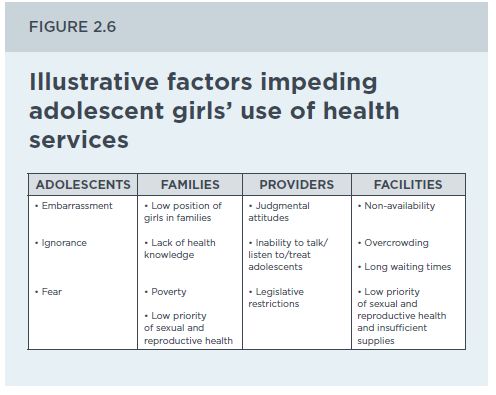

- Even though adolescence can be a particularly vulnerable period for exposure to multiple forms of violence, many health programmes are not designed to recognize and address the special needs of adolescent girls. Some of the various factors linked with adolescent girls’ difficult in accessing health services include:

Source: Excerpted from Temin, M. and Levin, R., 2009. Start with a Girl: A New Agenda for Global Health. Center for Global Development, p. 41.

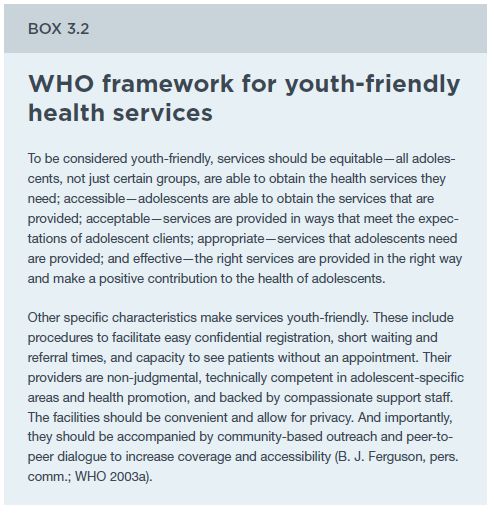

- Some factors considered by young people to be most important in youth-friendly services include confidentiality, privacy, short waiting time, low cost, and friendliness to both young men and young women (Erulkar, A.S., Onoka, C.J. & Ohir, A., 2005, cited in Shaw, 2009; Mmari, K.N. & Magnani, R.J, 2003; Kipp et al., 2007). Other key considerations that all health programming should take into account when working with adolescents are:

Excerpted from Temin, M. and Levin, R., 2009. Start with a Girl: A New Agenda for Global Health. Center for Global Development, p. 45.

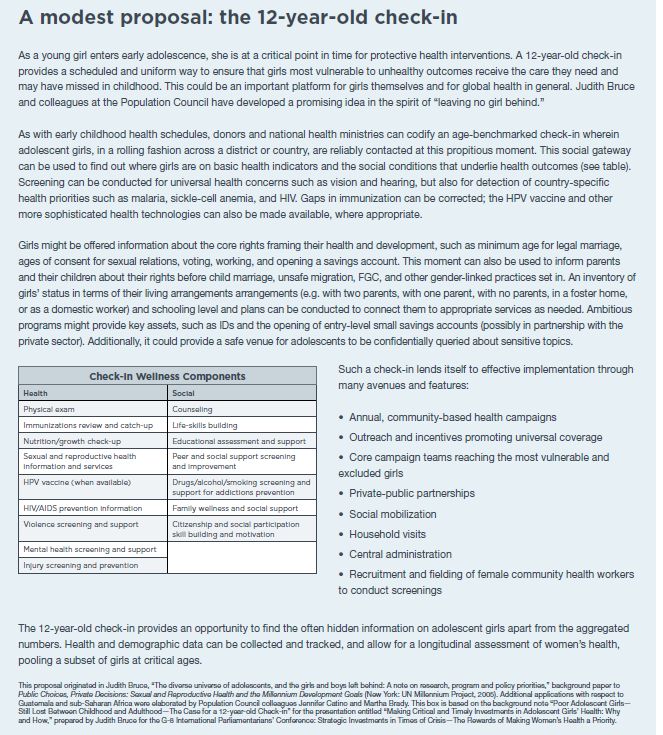

- As young girls are entering adolescence, the health sector may want to institute methods for assessing the particular vulnerabilities girls face in order to address their current needs and anticipate their future needs.

Excerpted from Temin, M. and Levin, R., 2009. Start with a Girl: A New Agenda for Global Health. Center for Global Development, p. 45.

In addition, different types of health services should tailor their services according to the specific needs of their adolescent patients. Sexual and reproductive health services are particularly relevant. Many reproductive health initiatives for young people have assumed that sexual activity is voluntary and therefore have aimed to help young people manage their sexual activity responsibly. This approach ignores evidence that many girls and young women experience forced sex and/or cannot negotiate sex, condom use or other contraceptives without fear of physical violence (Jejeebhoy and Bott, 2003). Some methods for improving reproductive health services include:

- Increased availability of contraception and other sexual health services for adolescent girls. This not only requires that health providers are sensitized the adolescent sexuality and are comfortable discussing sexual issues with adolescents, but also that sexual and reproductive health services and commodities are located in geographic areas convenient to adolescents, but that also promote privacy and confidentiality.

- Establishing linkages with the larger community. Even when health services do improve their capacity to respond to the needs of adolescents, community attitudes may discourage adolescents from seeking care and treatment (Mmari and Magnani, 2003). It is therefore critical that providers work with the community in promoting understanding of the importance of adolescents seeking and receiving sexual and reproductive health services.

- Universal screening for married adolescents. All married female adolescents should be considered high-risk and screened accordingly for violence. Prenatal and MCH services are the main entry point to reach girls in child marriage, at time of first pregnancy. Pre-natal and MCH health personnel should be trained to educate and treat girls in child marriages with sensitivity to their risks, vulnerabilities, and needs, including pre-term labour, adequate nutrition, importance of emergency obstetric care, referral for voluntary counselling and testing, etc.

- Establishing linkages with school-based services. When screening in health services reveals that pregnancy or STI/HIV infection is due to school-based sexual harassment, the health sectors needs to collaborate with the educational system so that all are working in concert to protect girls from rape. In addition, close cooperation with the educational system would allow the establishment of school-based services, usually an office within the school and a nurse trained in adolescent-friendly sexual and reproductive health care and in screening and counselling.

- Conducting prevention campaigns among youth on early marriage, teen relationship violence, sexual exploitation, etc.

Source: excerpted/adapted from: APIS Fundacion para la Equidad, Mexico: & Bustamente, N., 2007. Modelo de Atencion y Prevencion de la Violencia Familiar y de Genero: Nosotras en la Violencia Familiar. Mexico City, Mexico: APIS, Fundacion para la Equidad, A.C.

Example: In 2004, the Mexican NGO Instituto Mexicano de Investigacion de Familia y Poblacion (Mexican Institute of Family and Population Research) created a training programme for adolescents entitled, “Rostros y Mascaras de la Violencia” (Faces and Masks of Violence). This programme is directed at adolescents age 13 to 16 years and is provided in a low-income area of Mexico City thorough the government agency, “Desarollo Integral de la Familia” (Essential Family Development). The programme is 20 hours long (10 sessions of two hours each) and addresses the issue of violence in the context of friendships and relationships.

A survey conducted among 81 adolescents both before and after participating in this programme found that attitudes towards violence and relationships changed. This was demonstrated through an increase in correct answers to the following five survey questions (note correct answers to every issue listed is “false”): 1) Love means you can forgive anything (from 44% to 83%), 2) Jealousy is proof of love (from 28% to 77%), 3) Women who put up with violence do it for love (from 19% to 61%), 4) Men are violent by nature (74% to 83%), and 5) Only young and attractive women are raped (60 to 65%). The programme has developed a number of tools and set-up a YouTube channel that provides information on its programming as well as on IMIFAP campaigns against violence within “noviazgos” (dating relationships).

The tools are available in Spanish.

The videos are available in Spanish.

Source:Adapted from Instituto Mexicano de Investigacion de Familia y Poblacion

Case Example: Established in 1999, Geração Biz (Busy Generation) is a multisectoral adolescent reproductive health programme in Mozambique. Implemented by the Ministries of Health, Education, and Youth and Sports, with technical assistance from UNFPA and Pathfinder International, Geração Biz addresses the sexual and reproductive health needs of both in-school and out-of-school adolescents, giving attention to violence against women and girls. This is done through youth friendly clinical services, school-based interventions, community based outreach, peer education, and HIV/AIDS support. First implemented through two pilot sites in Maputo and in Zambézia Provinces, Geração Biz has since been extended to 62 districts in 10 of the country’s 11 provinces and involves 26 local organizations in programme implementation. At the request of UNFPA, an external evaluation of Geração Biz was conducted in 2004. The evaluation found evidence that Geração Biz had had a significant impact on young people’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. Heightened community awareness and sharply increased reporting of violence against women and girls were positive outcomes, but the evaluation showed that providers needed to incorporate more discussion on violence against women and girls within the context of youth friend service visits, even if the clients did not request it.

Source: adapted from: Hainsworth, G. and Zilhão, I., 2009. From Inception to Large Scale: The Geração Biz Programme in Mozambique. Geneva: World Health Organization, Pathfinder International.

Additional Resources:

The Family Health International Youth Net is a global programme committed to improving the reproductive health and HIV/AIDS prevention behaviours of youth 10-24 years of age. Family Health International publishes training materials that assist programme planners and those working in clinical settings to meet and understand the specific needs of youth. The materials are available in English.

The Coalition for Adolescent Girls is committed to creating lasting change for communities in the developing world by driving investments in adolescent girls. The idea behind this initiative is that when girls are educated, healthy and financially literate, they will play a key role in ending generations of poverty. For more information, see the website.

Meeting the Needs of Young Clients: A Guide to Providing Reproductive Health Services to Adolescents - Chapter 7: Counseling Victims of Sexual Violence (Family Care International, 2006). This guide is for health service providers. The chapter highlights the problem of forced sex for many adolescents and outlines key questions for health providers to ask during counseling sessions to identify young people who are survivors of or at risk for violence. Available in English and Spanish.

Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings: A Companion to the Inter-Agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings (United Nations Population Fund and Save the Children USA, 2009). This Toolkit provides user-friendly tools for assessing the impact of a crisis on adolescents, implementing an adolescent-friendly Minimum Initial Service Package, and ensuring that adolescents can participate in the development and implementation of humanitarian programmes. Other tools are specifically designed for healthcare providers to help them be more effective in providing and tracking services for adolescents at the clinic and community levels. Available in English.