All health facilities should engage in coordination at the facility-level and at the community level.

Facility-level coordination ensures that all those engaging with survivors within a facility are doing so according to the same standards and protocols. Facility-level coordination can also facilitate logistical oversight of equipment and supplies, as well as monitoring of quality of care. Facility-level coordination should be overseen by management of the facility.

Community-level coordination ensures that representatives from the health facility are part of a larger multisectoral network of providers and activists. Community-level coordination assists health facilities in linking with and working collaboratively with a local coordination network to:

- Establish ethical and safe referral pathways;

- Make rational and efficient use of local resources by avoiding duplication of efforts and harmonizing services;

- Develop allies and minimize discord;

- Promote transparency among providers;

- Improve monitoring of multisectoral responses;

- Link with sub-national and national coordination mechanisms.

- Successful community-level coordination is a challenge that requires active participation and commitment of those within health facilities who have the authority to make decisions on behalf of the facilities.

Coordination should be driven by a core set of principles that reflect and reinforce human rights and survivor-centred approaches. It is important for coordination actors to remember:

- The needs of survivors and those at risk of violence are the primary focus of coordination work;

- The coordination process should be well-structured in order to respect the time and participation of coordination partners. There should be sufficient human and financial resources allocated towards coordination; the meeting time and place should be specific and accessible; coordination meetings should be based on clear objectives and ground rules; and roles and responsibilities of coordination partners should be clear.

- Coordination should also be action-oriented and motivational, as well as provide an opportunity for reflection, social cohesion, and networking.

- A major benefit of effective coordination is establishing relationships with referral partners and creating standards for confidential and efficient referrals. However, participating in coordination is not the only method for identifying referral networks. Each health facility should be responsible for ensuring that they are able to provide women who disclose violence with information about where additional services--such as counseling, rape crises centres, shelters, legal assistance, social and material support--can be sought. Health facilities therefore have an obligation to find out what services exist in their communities and create a referral directory.

When establishing a referral directory, health facilities can follow the steps outlined below:

STEP 1: Determine the geographic area to be included in the referral network. Where do most of your clients live? How far can they travel to seek services? If the institution has clinics in several parts of the city or the country, each site may need a different directory to ensure that the services are geographically accessible to women.

STEP 2: Identify institutions in the area that provide services that are relevant for women and girls who experience violence. This list can include medical, psychological, social and legal organizations, as well as local police contacts. You may also want to consider including institutions that address secondary issues related to violence, such as alcohol and drug abuse, as well as those that offer services for children who have experienced or have been exposed to violence. Each institution may be able to name other local institutions that can be included in the directory.

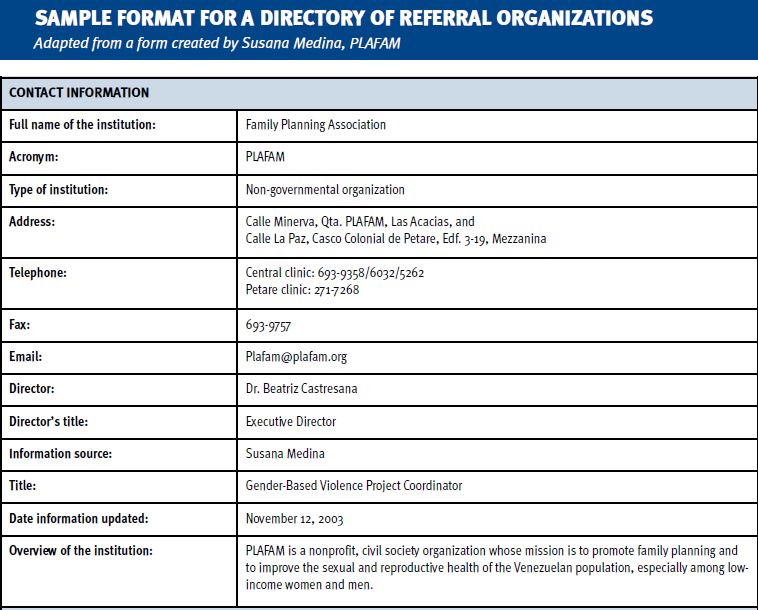

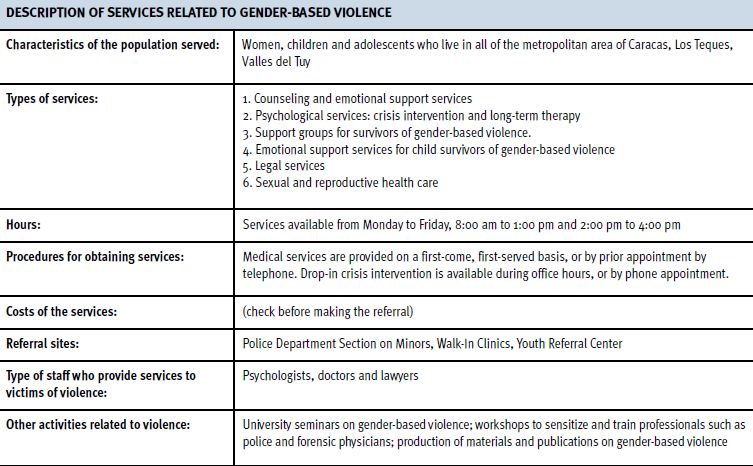

STEP 3: Call or (ideally) visit each institution to gather key information about its services. To ensure that you gather up-to-date information about each institution, and to have the opportunity to see the services firsthand, it is best to conduct a brief, informal interview in person with a staff member from the organization where services are provided. After describing your own work in the area of gender-based violence, you should ask a series of key questions to identify whether and how the institution can be used for referrals.

STEP 4: Organize the information into a directory. You can organize information about referral institutions in different ways (for example, by location, type of service offered, etc.). If the number of referral services available in the community is small, then the directory may be very concise. If the directory is long, an index of institutions by name and type of service can make a directory more user-friendly.

STEP 5: Distribute the directory among health care providers. Ideally, a health programme should distribute a copy of the directory to each health care provider so that all staff members who interact with female clients have access to this information. If resource constraints make it difficult to print this many copies, then every clinic should have a directory available to staff in a convenient, accessible place.

STEP 6: Gather feedback from providers about how well the directory is working. Managers should take the time to discuss the directory with providers soon after it is introduced to make sure that the format is workable and that the providers have not had any difficulties with the process of making referrals. Once providers have used the directory for a period of time, they may know what referral services are or are not in fact accessible to their clients, for example.

STEP 7: Formalize relationships with referral institutions. After creating a directory, the next step is to create more formal partnerships with other agencies. This may include setting up formal referral and counter-referral systems, as well as collaborating on projects. In some cases, IPPF member associations have negotiated discounted prices for their clients. Ideally, organizations involved in a referral network should be in contact with one another on a regular basis to give feedback, stay up-to-date, and provide at least minimal follow-up to selected cases and other issues related to this work.

STEP 8: Update the information in the directory on a regular basis. It is essential for health programs to update the information in the directory on a regular basis (for example, every six months) to avoid giving women misinformation. Not only can misinformation waste women’s time, money and energy, but it can also put them at risk in a number of ways. Remember that services can close, relocate, raise their costs, or change their procedures, especially in resource-poor settings where funding is scarce.

Source: excerpted from Bott, S., Guedes, A., Guezmes, A., and Claramunt, C., 2004. Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Professionals in Developing Countries. New York: IPPF/WHR, pg. 61. Available in English and Spanish.

Excerpted from: Bott, S., Guedes, A., Guezmes, A. and Claramunt, C., 2004. Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Professionals in Developing Countries. New York: IPPF/WHR, p. 63. Available in English and Spanish.

Additional Resources:

Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-based Violence: A Resource Manual for Health Care Professionals in Developing Countries (Bott, S., Guedes, A., Guezmes, A. and Claramunt C./ International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region, 2004). See Section III.e.: Developing Referral Networks. Available in English and Spanish.

Bridging Gaps—From Good Intention to Good Cooperation (Women Against Violence Europe, 2006) This manual is a resource for service providers across sectors addressing violence against women. The manual offers guidance and recommendations on multi-agency cooperation in the protection of domestic violence survivors. The manual is organized into 15 chapters covering: background information on violence against women; multi-sector service provision and multi-agency cooperation; general and sector-specific standards for practice; violence prevention and safety planning; survivor involvement in programmes; actions and models for multi-agency cooperation. Available in English; 116 pages.

Guidelines on Coordinating GBV Interventions in Humanitarian Settings (Ward, J. 2010). New York: Gender-based Violence Area of Responsibility Working Group. Available in English.

Community of Practice in Building Referral Systems for Women Victims of Violence, (Jennings, M./UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, 2010). Available in English.