- A public health surveillance system is necessary to understand the consequences of violence against women and girls; to determine the costs associated with violence; and to monitor the scope, coverage and quality of care survivors are receiving (Ellsberg and Arcas, 2001).

- A public health surveillance system may also contribute to understanding the prevalence and incidence of violence against women and girls, though it is very important to remember that surveillance systems based on service-delivery data only provide information on women and girls who report or seek help for violence. Many women who experience violence will not report to a health facility or disclose that they have experienced abuse. Service delivery data is therefore more useful in monitoring demand for services, capacities of service providers to respond, and the number and scope of services provided. Prevalence is better measured through population-based surveys, as described in Conducting Research, Data Collection and Analysis in the Programming Essentials module.

- Ideally, surveillance will be based on a national system to collect, track and report data on violence against women by the public health system that is aligned at the sub-national and local levels. The best way to collect data is electronically and stored in a centralized location.

WHAT IS PUBLIC HEALTH SURVEILLANCE?

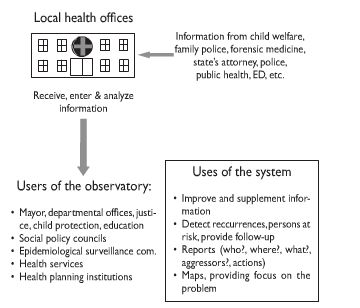

- Public health surveillance is “the ongoing systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of outcome-specific data for use in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice.” Typically, public health surveillance includes data collection and analysis, as well as dissemination of data to those who are responsible for undertaking prevention and response programming. Surveillance data is not only useful in terms of identifying health service needs of a given population, but also for understanding research and training needs. Public health officials usually have responsibility for overseeing any kind of public health surveillance system.

- Planning a surveillance system begins with a clear understanding of the purpose of surveillance—e.g. the problem that is being studied—after which begins a process of deciding how best to obtain, analyze and disseminate information about the problem. Public health data can be drawn from a variety of different sources, such as hospital discharge records, medical management information, police records, etc. However, it is important to remember that while these data systems can be used for surveillance, they are not surveillance systems in and of themselves. Surveillance is a larger process that requires analysis, interpretation, and use of the data.

- It is important to remember that surveillance systems are ongoing, require and the input and participation of many individuals and organizations, and must provide information that is timely enough to be acted upon.

- The general steps for developing a surveillance system include:

1. Establish objectives

2. Develop case definitions

3. Determine data sources data-collection mechanism (type of system)

4. Determine data-collection instruments

5. Field-test methods

6. Develop and test analytic approach

7. Develop dissemination mechanism

8. Assure use of analysis and interpretation

Source: excerpted from Teutsch S, Thacker S: Planning a public health surveillance system. Epidemiological Bulletin 1995, 16(1), pgs.1-6)

- In order to contribute to a surveillance system, all providers should be using standardized medical records and information systems on violence against women and girls in order to generate comparable data—meaning that each agency or institution should have intake and other client forms that utilize nationally-determined case definitions and that document similar case information (Kilonzo, 2008a). Each agency or institution should also have a method for centralizing and reporting data that is not linked to names or other identifying information to ensure survivor safety and confidentiality (Ellsberg and Arcas, 2001). Data collection forms and methods should not be unduly complicated, and health care providers should be trained in data collection.

- Data collected at the clinic and hospital level should be forwarded to the municipal level, then to the district level, and then to the national level (Ellsberg and Arcas, 2001). While it is critical that a designated office or institution at the national level is tasked with overseeing the surveillance system, data should not only be analyzed at the national level; it should also be analyzed at the clinic, hospital, municipal, and district levels to improve services, prepare budgets and as a basis for planning.

Example: In Belize, Guatemala, and Panama, a single registration system has been developed that is intended to be used by professionals from all sectors that come into contact with violence victims, such as the Ministries of Health, law enforcement, the court system, and non-governmental organizations. The system also applies to reports by forensic doctors. In Belize, the Ministry of Health is responsible for consolidating, processing, and analyzing the information from these sectors and then afterwards reporting it to the other pertinent ministries. In Panama, the information is sent to the Legal Medicine Institute for analysis.

Lessons learned from this approach are that information and surveillance systems are an essential part of the integrated approach to gender-based violence and should not function independently from the development of services. For the reporting system to work, and before it is implemented, it is important to develop norms and protocols for the detection and care of the affected women and to train providers in their appropriate use. Untrained personnel can actually cause harm to women by asking about violence in insensitive or victim-blaming ways.

Furthermore, information systems are only valid if the data are used to improve services. Not only is it a waste of resources, but also it is unethical to collect information or carry out active screening for violence with the sole purpose of information-gathering, if no services are offered in return

Source: Excerpted from Velzeboer, M., Ellsberg, M., Arcas, C., and Garcia-Moreno, C., 2003. Violence against Women: The Health Sector Responds. Washington, DC: PAHO, pgs. 55-57.

Example: The province of Valle, Colombia created a domestic surveillance system with the support of the Secretary of Health of Valle. This was done using resources from the basic health plan allocated for strengthening the municipal reporting system and response to domestic violence. By creating an active surveillance system, a municipality with 185,000 inhabitants increased the documented cases of violence against women and girls from 192 in 2002 to 1,059 in 2004 – a fivefold increase in reported cases over a three-year period. Reliability and validity of data also improved. Strategies included: implementation of a standard digitalized reporting and analysis system along with advocacy with community decision makers; strengthening inter-institutional attention networks; consulting for constructing internal flow charts; sensitizing and training network teams in charge of providing health care in cases of domestic violence and supporting improved public policy prevention initiatives. The system was useful for improving survivor services. The project was phased in, with sites added in over a three-year period. The system created geographic references and plotted where reported cases of violence against women and girls occurred; developed a prevention strategy for early detection of violence against women and girls; constructed charts for decision making for each institution; and constructed a common protocol and flow chart for referral of survivors within a network of inter-institutional prevention and treatment. Standardized information gathering in a common software programme became an epidemiological surveillance system including all cases within a defined population, with active collection, consolidation and verification procedures.

Source: Adapted/Excerpted from: Espinosa, R., Gutiérrez, M.I., Mena-Muñoz, J.H., Córdoba, P., 2008. “Domestic Violence Surveillance System: A Model”, pp. S13-S16.

Illustrative Resources:

Domestic Violence Surveillance System: A Model (Espinosa, R., Gutierrez, M., Mena-Munoz, J. and Cordoba, P. 2008). Salud Publica de Mexico 50 (Issue Supplement 1): S12-S18. Available in English.

Data Collection System for Domestic Violence (The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2002). Available in English.

Sexual Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002). Available in English.

Administrative Data Collection on Domestic Violence in Council of Europe Member States (Council of Europe. 2008). Available in English.

Gender-based Violence Information Management System Project Tools. The GBVIMS is a multi-faceted initiative being undertaken in humanitarian settings to enable humanitarian actors to safely collect, store, and analyze reported GBV incident data. The GBVIMS includes: a workbook that outlines the critical steps agencies and inter-agency GBV coordination bodies must take in order to implement the system; an Excel database (the “Incident Recorder”) for data compilation and trends analysis; and a global team of GBV and database experts from UNFPA, UNHCR and the International Rescue Committee for on-site and remote technical support. For more information about the tools, see the information brief and the website.

For general tools on collecting data on violence against women and girls, see Conducting Research, Data Collection and Analysis in Programming Essentials.