- In order for the health sector to develop and implement comprehensive services, relevant laws must be in place. Some of these laws will focus broadly on the problem of violence against women. There are others that will be more specific to health services for survivors. Those wishing to improve health sector programming should assess and, if necessary, work to reform laws in key areas related to quality of care and the rights of survivors. (Bott, Morrison, and Ellsberg, 2005a)

- The process for developing legislation on violence against women and girls is described in detail in the module on legislation. Issues specifically pertaining to the health sector are excerpted from that module and are elaborated below.

1. Review laws related to the health sector and violence against women and girls.

- In general, regardless of the type of violence, health-related legislation should include a statement of the rights of survivors that promotes survivor safety and assistance and preserves confidentiality, and also seeks to prevent re-victimization. Legislation should name an agency or agencies responsible for victim services and should clearly describe the responsibilities of the agency or agencies. The legislation should clearly identify the services provided for different types of violence and the obligation of health providers to offer comprehensive services. The legislation should also mandate coordination, implementation, and funding mechanisms to ensure those services are established, monitored and evaluated.

- Key components for domestic violence:

- Legislation should mandate access to health care for immediate injuries and long-term care including sexual and reproductive health services, emergency contraception, HIV prophylaxis and safe abortion (where legal) in cases of rape.

- Legislation should mandate protocols and trainings for health care providers, who may be the first responders to domestic violence. Careful documentation of a survivor’s injuries will assist a survivor in obtaining redress through the legal system.

- The law should prohibit the disclosure of information about specific cases of domestic violence to government agencies without the fully informed consent of a complainant/survivor, who has had the opportunity to receive advice from an advocate or lawyer, unless the information is devoid of identifying markers (i.e. the information is presented in such a way that the victim’s identity cannot be discerned).

- Legislation should include provisions that require agency collaboration and communication in addressing domestic violence. NGO advocates who directly serve domestic violence victims should have leadership roles in such collaborative efforts.

Examples of nations with provisions which mandate cooperation by state agencies:

- An objectives of Albania‘s Law On Measures for Prevention of Violence In Family Relations (2006) is: a. To set up a coordinated network of responsible authorities for protection, support and rehabilitation of victims, mitigation of consequences and prevention of domestic violence. Article 2.

- The Anti-Violence Against Women and their Children Act (2004) of the Philippines includes the following provisions on community collaboration:SEC. 39. Inter-Agency Council on Violence Against Women and Their Children (IAC-VAWC). In pursuance of the above mentioned policy, there is hereby established an Inter-Agency Council on Violence Against Women and their children, hereinafter known as the Council, which shall be composed of the following agencies: Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD); National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women (NCRFW); Civil Service Commission (CSC); Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC); Department of Justice (DOJ); Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG); Philippine National Police (PNP); Department of Health (DOH); Department of Education (DepEd); Department of Labour and Employment (DOLE); and National Bureau of Investigation (NBI).

These agencies are tasked to formulate programs and projects to eliminate VAW based on their mandates as well as develop capability programs for their employees to become more sensitive to the needs of their clients. The Council will also serve as the monitoring body as regards to VAW initiatives…

SEC. 42. Training of Persons Involved in Responding to Violence Against Women and their Children Cases. – All agencies involved in responding to violence against women and their children cases shall be required to undergo education and training to acquaint them with: the nature, extend and causes of violence against women and their children; the legal rights of, and remedies available to, victims of violence against women and their children; the services and facilities available to victims or survivors; the legal duties imposed on police officers to make arrest and to offer protection and assistance; and techniques for handling incidents of violence against women and their children that minimize the likelihood of injury to the officer and promote the safety of the victim or survivor….

- Spain‘s Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence Law (2004) states that ―The female victims of gender violence are entitled to receive care, crisis, support and refuge, and integrated recovery services…Such services will act in coordination with each other and in collaboration with the Police, Violence against Women Judges, the health services, and the institutions responsible for providing victims with legal counsel, in the corresponding geographical zone. Art. 19 Spain‘s law also provides for funding and evaluation of these coordination procedures.

- Key components for sexual violence:

- Legislation should provide that survivors have the right not to be discriminated against, at any step of the process, because of race, gender, sexual orientation or any other characteristic. See: UN Handbook, 3.1.3.

- Legislation should provide for a comprehensive range of health services which address the physical and mental consequences of the sexual assault. These services should include: one rape crisis centre for every 200,000 population; programmes for survivors of sexual assault; survivor witness programmes; elderly survivor programmes; sexual assault survivor hotlines; and incest abuse programmes. See: UN Handbook 3.6.1 and 3.6.2. The legislation should include a plan to provide survivors with this information. See: Minnesota, USA Statute §611A.02; the Rape Victim Assistance and Protection Act (1998) of Philippines. Legislation should provide that access to these services need not occur within a particular time frame and that access is not conditional in any respect. See: World Health Organization, ―Guidelines for Medico-Legal Care for Victims of Sexual Violence (2003). Available in English.

Lesson learned: In many countries there is legal requirement that sexual assault be reported to the police. This is called mandatory reporting and is most common where there has been sexual assault of children. In some countries there is an expectation that incidents will be reported to the police before health care is accessed, indeed it has been inculcated as a practice in the health sector that victim/survivors give a statement to the police before they receive health care. Whilst health workers clearly have to follow the law of their country, it is not desirable that health sector policy privileges justice needs over health needs. Health services should be accessible before cases are reported to the police, and health and justice policies should clarify this (Jewkes, 2006). Mandatory reporting has also been found to discourage women from seeking needed health care and discouraged health providers from asking questions related to violence, for fear that they will get involved in court cases (Velzeboer, 2003).

- Legislation should ensure that the costs of forensic examination to gather and preserve evidence for criminal sexual conduct shall be paid for by a local government body in which the sexual assault occurred. See: Sexual Offences Act (2003) of Lesotho, Part VI, 21 (1).

- The collection of forensic evidence should be decentralized. DNA capacity, conducting exams and writing reports should be expanded to a greater number and levels of providers, such as nurses and midwives as well as physicians (Kilonzo, 2008a). Experience has shown that forensic nurse examiners have reduced waiting and assessment times for medical forensic exams; increased the number of sexual assault kits completed; generated more accurate and complete sexual assault kits; improved the chain of evidence or custody; aided law enforcement officials in collecting information and laying/filing charges; and enhanced the likelihood of prosecution and conviction (Excerpted from: Du Mont, J. and White, D., 2007. The Uses and Impact of Medico-legal Evidence in Sexual Assault Cases: A Global Review. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, pg. 37). These measures need to be followed up by implementation by other relevant actors (e.g. prosecutors) to ensure the evidence is processed and used.

Lessons learned: Many countries restrict the collection of forensic evidence to specially certified doctors, such as district surgeons or forensic physicians. The low numbers and availability of certified doctors poses a challenge to women who want to access these services. Women are often required to wait long periods and to navigate complicated paths to get the care they need. In some settings, forensic exams are often used (unreliably) to establish whether and when a girl or woman lost her virginity--evidence that may be used against her in court (Human Rights Watch, 1999; Brown, 2001). A number of countries are working on expanding and providing better services, including through professionalization and training of additional health care personnel.

- Legislation should provide for cost-free and unconditional tests for sexually transmitted diseases, emergency contraception, pregnancy tests, abortion services, and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is ―short-term antiretroviral treatment to reduce the likelihood of HIV infection after potential exposure, either occupationally or through sexual intercourse. From: World Health Organization. See: Stefiszyn, ―A Brief Overview of Recent Developments in Sexual Offences Legislation in Southern Africa, expert paper prepared for the Expert Group Meeting on good practices in legislation on violence against women, May 2008.

- Legislation should provide for a coordinated community response for survivors of sexual assault. See: Coordinated Crisis Intervention, StopVAW, the Advocates for Human Rights.

- Legislation should provide for coordinated sexual assault response teams or programmes to give survivors a broad range of necessary care and services (legal, medical, and social services) and to increase the likelihood that the assault can be successfully prosecuted. Such programmes or teams should include a forensic examiner, a sexual assault advocate, a prosecutor, and a law enforcement officer. All responding actors should follow specific protocols that outline their responsibilities in treating and providing services to survivors of sexual assault.

- Legislation should mandate dedicated funding to ensure the appointment of sexual assault service providers, their registration as service providers, and to provide for their specialized training. See: Good practices in legislation on ―harmful practices against women (2010) 3.4.2 and 3.4.3.

- Legislation should include all necessary provisions for full implementation of the laws on sexual assault, including development of protocols, regulations, and standardized forms necessary to enforce the law. Legislation should require that these protocols, regulations and forms be developed within a limited number of months after the law is in force, and legislation should provide a fixed time that may pass between the adoption of a law on sexual assault and the date that it comes into force. See: UN Handbook, 3.2.6 and 3.2.7.

- Legislation should provide for a specific institution to monitor the implementation of the laws on sexual assault, and for the regular collection of data on sexual assaults. See: UN Handbook, 3.3.1 and 3.3.2.

Example: Sexual Offences Act (No.3) (2006) of Kenya (2006) includes the following provision: ―The Minister shall (a) prepare a national policy framework to guide the implementation, and administration of this Act in order to secure acceptable and uniform treatment of all sexual related offences including treatment and care of victims of sexual offences; (b) review the policy framework at least once every five years; and (c) when required, amend the policy framework. Section 46

Additional Resources:

See Tools for Developing Legislation on Domestic Violence and Tools for Drafting Legislation on Sexual Assault in the module on Developing Legislation on Violence Against Women and Girls. The module also contains information on legislation related to sexual harassment, sex trafficking, harmful practices, forced and child marriage, female genital mutilation/cutting, honour crimes, maltreatment of widows and dowry-related violence.

2. Conduct advocacy to upgrade laws.

- Often, advocacy is misunderstood as synonymous with behaviour change communication (BCC)/ information, education, communication (IEC) and/or community mobilization. Although these activities are targeted toward promoting change and involve developing messages tailored to a specific audience, advocacy stands apart from these approaches because the ultimate goal of advocacy is policy change. The advocacy process is complete when a decision-maker takes a prescribed policy action. While raising awareness of the general public may be an important step in this process, it is not the ultimate goal.

- A collective voice is often much stronger than a solitary voice, and speaking out collectively avoids backlash being directed at a lone individual or organization, especially when an issue is controversial or difficult. For that reason, advocacy efforts are often best undertaken by a coordinated group of key stakeholders who are, for example, organized as a coalition. Health actors should work within a coordination mechanism to develop and implement advocacy efforts.

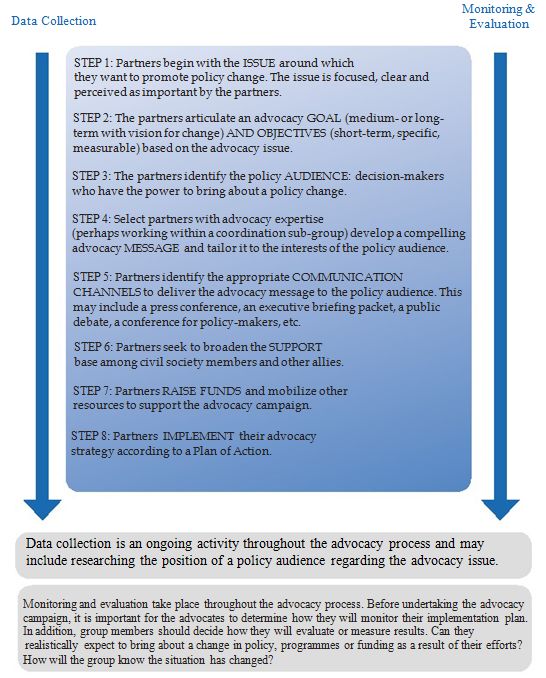

- The following presents a brief overview of an advocacy process (excerpted from Ward, 2010 and adapted from CEDPA, 2000).

Case Study: The South African Gender-Based Violence and Health Initiative (SAGBVHI)

Health sector coalitions can play an important role in advocating for public policy and institutional reform. For example, the South African Gender-Based Violence and Health Initiative (SAGBVHI) consists of 15 partner organizations and individuals in South Africa. They conduct research, build research capacity, disseminate research findings, and use research to advocate for policy reforms. SAGBVHI works closely with the Gender and Women's Health Directorates of the National Departmentof Health. The impact such networks produce are difficult to measure, but informal assessments suggest that SAGBVHI has achieved important results. For example, they convinced two medical schools to increase their emphasis on gender-based violence within their curriculum, helped to develop a one-week module on rape for medical students, and contributed to new national policies on gender-based violence and health. Their work exemplifies how researchers can collaborate with government to translate research findings into policy (Medical Research Council, 2003; Guedes, 2004).

Excerpted from: Bott, S., Morrison, A., Ellsberg, M., 2005a. Preventing and Responding to Gender-based Violence in Middle and Low-income Countries: A Global Review and Analysis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3618, p. 28.

For more detailed information on advocacy related to legislative reform, see Advocating for New Laws or the Reform of Existing Laws in the module on Legislation.

Additional Resources:

Women Leadership Program Initiative for Equity Tanzania (Women Leadership Program Initiative for Equity Tanzania, 2003). This resource provides practitioners and trainers a comprehensive overview of a leadership training to address GBV. The training develops community change agent skills, with topics including gender concepts, the linkage between GBV/VAW and human rights, communication for advocacy against GBV and developing action plans for networking. The workshop objectives, agenda, outcomes and facilitation methodology are provided alongside the workshop evaluation as a reference to the training. Available in English; 52 pages.

Gender, Reproductive Health, and Advocacy (Centre for Development and Population Activities, 2000). Training Manual Series. (Sessions 9-14). Available in English.

3. Ensure that laws are implemented.

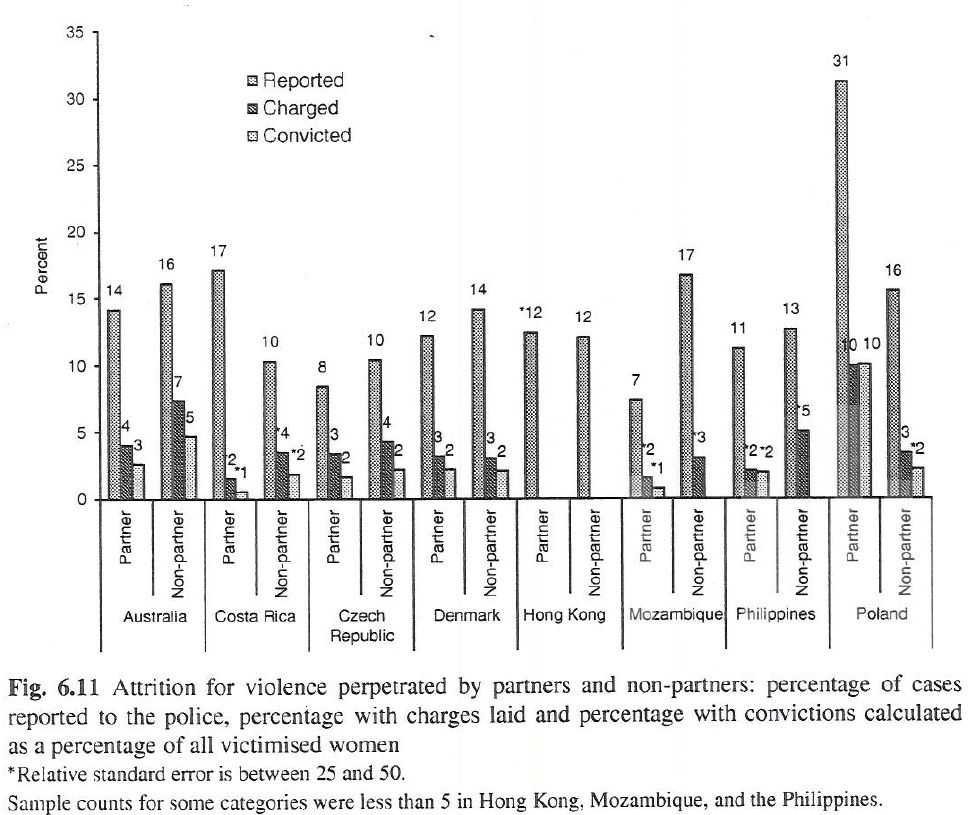

- In the absence of enforcement, even the best laws do not prevent violence or protect survivors. Globally, rape is among the least convicted of all crimes. On average, only ten percent of reported violence will result in a conviction, and in many settings, that number is likely to be even lower (Amnesty International, 2004, cited in USAID and UNICEF, 2006; Johnson et al. 2008; Vetten et al. 2008; and Lovett and Kelly 2009).

Source: Johnson et al. 2008. Violence against Women: An International Perspective. Springer: New York.

- Particularly in some developing countries, marital rape is not defined as a crime. Even where there are laws against intimate partner violence, they often go unrecognized, carry light sentences—of which just the minimum is often applied—or are compromised by customary law, which often dictates that husbands may use a certain degree of violence against their wives to discipline them (Center for Reproductive Law and Policy, 2001, cited in USAID and UNICEF, 2006).

- Budgetary constraints, low political commitment, and/or limited popular support of women’s rights and a lack of training for lawyers and judges in the application of relevant laws, policies, and protocols also undermine the implementation of protective legislation. Furthermore, many women have little access to information about their rights and how to negotiate the legal system when their rights are violated (USAID and UNICEF, 2006).

- The health sector therefore has a responsibility to ensure that laws related to the rights of survivors to services and the obligations of health care providers are properly implemented. Facilitating implementation involves training health care providers about their obligations related to relevant laws, ensuring that communities are aware of their rights and the availability and range of services, and monitoring delivery of services and quality of care. For more information about Implementing Laws see the module on Developing Legislation on Violence Against Women and Girls.