1. Violence against women and girls is a major cause of morbidity and mortality.

- Many women and girls do not typically seek out health care specifically related to their victimization, or do not acknowledge to health providers that they are seeking assistance because of victimization. Nevertheless, violence against women and girls is linked to many serious health problems, not only at the time the violence occurs but throughout life.

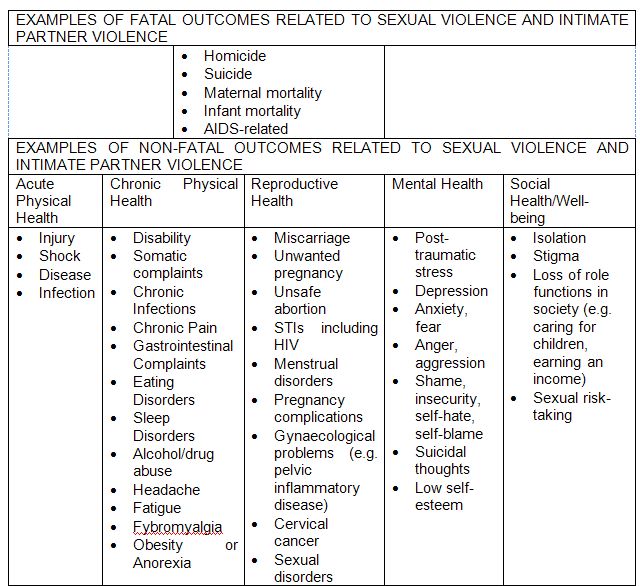

- Violence against women and girls is increasingly understood as a risk factor for a variety of diseases and conditions, and not just as a health problem in and of itself. Exposure to physical and sexual violence can result in a wide range of immediate and chronic health problems specifically related to the assault, and may also contribute to negative behaviours that affect long-term health and well being, such as smoking and alcohol and drug abuse (Brener, McMahon, Warren, & Douglas, 1999).

Sources: For health consequences of sexual violence and intimate partner violence identified above, see Campbell, 2002; Heise and Garcia-Moreno, 2002; Ellsberg, 2006; Garcia-Moreno and Stöckl, 2009; World Bank Gender-Based Violence, Health and the Role of the Health Sector website page.

- Violence against women and girls can also have an impact on maternal health and infant and child morbidity and mortality. Although violence is often not a part of health screening, when it has been included as a part of antenatal care, intimate partner violence during pregnancy is among the common conditions identified (Ellsberg, 2006). Violence and has been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as low birth weight, premature labour, pre-term delivery, miscarriage, and foetal loss (Campbell, Garcia-Moreno, and Sharps, 2004; Ellsberg et al., 2008; Garcia-Moreno, 2009).

- Girls who experience sexual abuse in childhood may be more likely to engage in sexual risk-taking later in life, compounding their long-term risk of sexually transmitted diseases and early pregnancy (WHO, 1997, cited in Ward et al., 2005).

- Girls who are forced or coerced into child marriage (before the age of 18) are at risk for a variety of negative health outcomes. Complications from pregnancy and childbearing the leading cause of death for 15-19 year-old girls worldwide (Black, 2001, cited in Ward et al., 2005). Girls who marry early may also be at greater risk of intimate partner violence, especially in relationships where their husband is significantly older (Ward et al., 2005).

- Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), considered to be a form of violence against women and girls, also has a wide range of maternal and child health consequences.

|

Obstetric Sequelae of FGC/M in Earlier Life

|

Childbirth Sequelae of FGC/M in Pregnancy |

|

Antenatal Effects:

|

Antenatal Effects:

|

|

Effects During Labour and Delivery:

|

Effects During Labour and Delivery:

|

Source: World Health Organization. 2000. A Systematic Review of the Health Complications of Female Genital Mutilation Including Sequelae in Childbirth. Geneva: WHO. See also the World Health Organization Female Genital Mutilation website page.

- Violence against women and girls also has a social health dimension: it can contribute to diminished functioning in relationships, families and the workplace, impacting overall capacity of survivors to fulfill their potential and engage with and contribute to society (Golding, 1996).

Additional Resource:

See an overview by the World Health Organization of the health effects of various types of violence against women.

2. Survivors who visit health clinics where providers are not trained to recognize and address violence against women and girls may be misdiagnosed or otherwise receive inappropriate care.

- If health care providers are not well-trained in the consequences of violence against women and girls, they may not be able to detect the indicators of abuse, preventing them from effectively treating the survivor and/or providing appropriate referrals for emotional, legal, housing and other services that can support survivors and end the abuse.

- Health care providers who themselves have experienced abuse and do not have sufficient professional training and support may avoid addressing the issue with survivors who present for assistance.

- Overlooking the health implications of violence is not just a missed opportunity. It is a violation of medical ethics. Providers may fail to provide holistic care, to recognize women in danger, or to provide necessary, even life-saving care, such as STI treatment and/or post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV.

- In addition, providers who are not trained in addressing violence against women and girls may respond to clients who report violence with victim-blaming attitudes that may inflict further emotional harm (Kim and Motsei, 2002) and discourage women from seeking treatment. At the very minimum, health care providers should seek to ‘do no harm’ when engaging with survivors so as not to revictimize those who have experienced violence.

- When health care providers are not trained in the guiding principles of working with survivors, such as when providers do not protect patient confidentiality, women and girls may be at risk of additional violence from partners and/or family members (World Bank, 2002).