Safe cities for women programme partners should keep track of the positive or negative changes, achievements, challenges, and new information that result from their actions. This can be done through a combined use of monitoring and evaluation. Monitoring is the process of tracking the progress of safe cities for women actions as they happen, in order to (a) determine if they are successful and (b) learn from their outcomes. Monitoring is important because it helps partners to decide what actions have been the most helpful and what actions have been the least helpful for women in the community. This information can then be used to focus resources on continuing successful actions, and improving or stopping less-successful actions. In order to monitor programme actions, partners should agree on a set of indicators that will show whether or not expected changes are occurring as a result of their actions. An indicator is a piece of information that can be recorded and measured to show how close one is to achieving one’s goal – it is a kind of measure to show change. It is very important to choose indicators that truly apply to the kind of changes a safe cities programme is aiming to effect. Some examples of success indicators relevant for a safe cities for women programme, depending on the specific approach, are: use of public space by women and girls, coverage of women’s safety concerns in the local media, or women’s participation in urban planning initiatives. Remember that even though women and girls in different cities face similar problems, the specific indicators might be quite different from one place to the next.

It should be mentioned that measuring social change associated with gender relations is extremely challenging and necessarily requires monitoring over several years. Mechanisms for both monitoring and evaluation have to be well-designed and innovative in order to capture the processes of how change happens and/or how gender relations have been altered (Batliwala and Pittman, 2010).

Identify indicators.

It is helpful for all safe cities for women partners to discuss and reach agreement on the changes that they expect to see in relation to each action that is taken. Once this is decided, indicators can be identified and developed. The indicators chosen should be the ones that remain most important and meaningful to measure change within the particular initiative or programme, and easy to gather throughout its duration. Consider whether it is feasible to use indicators at more than one scale (Whitzman 2008b, pp. 192-199). (Different scales include: the individual level, the inter-personal level, the household level, the neighbourhood level and the city-wide level, the short-term level and the long-term level). For example, if safe cities for women programme partners are focusing on community awareness, some indicators they could use to measure the impact of their actions include:

- Proportion of individuals who know any of the legal rights of women;

- Proportion of individuals who know any of the legal sanctions for violence against women and/or girls;

- Proportion of people who have been exposed to messages about public violence against women and girls;

- Proportion of people who believe that women provoke attacks in public based on how they act or dress, or where or when they travel;

- Proportion of people who believe that sexual harassment is acceptable and/or not harmful to women;

- Proportion of people who believe that women and men experience the same level of safety in public space;

- Proportion of people who believe that men and women use public space in the same fashion;

- Proportion of people who say that men cannot be held responsible for controlling their sexual behaviour.

Adapted from page 33 of Bloom, S. (2008). Violence against Women and Girls: A Compendium of Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: MEASURE. Available in English.

Resources:

Observatorio cuidades, violencias y genero (Observatory on cities, violence and gender) (2010). This online resource centre, developed by the Women and Habitat Network with support from UNIFEM and AECID, aims to produce and disseminate information on gendered violence and women's insecurity in cities; to monitor and analyse the effects and impact of urban policies and programmes related to gender; and to produce new knowledge on women's safety that contributes to social and public policy agendas, particularly at the local level. The Observatory features a four-part indicator matrix on gendered violence in cities. Specifically, the indicator matrix addresses the following thematic areas: institutional context; diagnosis and measurement of the impact of gendered violence; policies and actions to prevent and eliminate violence against women; and communication and information on violence against women. Available in Spanish.

2005 - 2009 Gender Sensitive Indicators in Seoul (2010). This publication, created by the Seoul Foundation of Women & Family, presents a set of indicators used in Seoul, South Korea, to measure and monitor the status of women's lives. Indicators are divided into four categories: Women's Economic Empowerment; Social Integration of Minority Women; Expansion of the Social and Cultural Rights of Women; and Enhancement of Women's Political Participation and Representation. Within these indicators, women's feelings of safety and security in the city are included. In the publication, the significance of each indicator used is presented, as are the method of measurement and results of each indicator. English.

Methodologies to Measure the Gender Dimensions of Crime and Violence (Elizabeth Shrader, 2001). The World Bank - Latin American and Caribbean Gender Unit. This guide outlines different methods for measuring gender-based crime and violence. The methods covered include the following: homicide rates, crime statistics, victimization surveys, prevalence surveys, service statistics, knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) studies, opinion polling, victim interviews, focus groups, participatory appraisal (rural and urban), and more. Each methodology is explained and its benefits and drawbacks are discussed. Available in English.

Indicadores Urbanos de Género Instrumentos para la gobernabilidad urbana (Instruments for Urban Governance: Urban Gender Indicators) (Rainero, L. and M. Rodrigou, no date). CISCSA – Women and Habitat Network of Latin America and the Caribbean. This article describes the process of building urban gender indicators, including a discussion of motivations and usefulness. It also describes the theoretical assumptions that support urban gender indicator development. The indicator-building process described in this document occurred while designing a survey that was given to women and men in different Latin American cities. Survey questions explored how women and men use public spaces differently and how feelings of insecurity and actual insecurity affect women more than men in public spaces. This article was developed within the Programme Indicadores Urbanos de Género Instrumentos para la gobernabilidad urbana CISCSA – Women and Habitat Network of Latin America and the Caribbean. Supported by the Regional Office for Brazil and the Southern Cone – UNIFEM. Available in Spanish.

“Developing Equality Objectives and Monitoring” guide in The Equality Standard for Local Government (Improvement and Development Agency (IDeA), 2007). IDeA, United Kingdom. This guide provides instructions for government bodies, including public planners, on setting standards for and monitoring equality in their practices. The publication is formatted as a step-by-step guide with background information, criteria, and examples provided for each step. Available in English.

Remember that indicators involving violence against women and girls can have ethical consequences.

Safe cities for women programme partners may use surveys, interviews or focus groups to determine whether or not their activities are producing the desired changes with respect to a specific indicator. If this indicator involves women’s or girls’ experiences of violence, it is likely that any personal responses on their part will be difficult and emotional. Additionally, interviews on such sensitive issues, if not done with proper training and care, can put interview subjects at risk of revictimization. For example, if a woman is suffering from partner abuse, and her partner finds out she has provided information about the abuse to a third party, this may anger her partner and cause him to abuse her more.

Partners should also be aware that the results of these kinds of interviews, surveys and focus groups may not be completely accurate because some women and girls will not report incidents of violence because they do not feel comfortable sharing such personal information. Alternatively, women and girls may not report violence they have experienced because they do not identify those incidents as abnormal or undeserved (Bloom, 2008, p.19). These facts should not discourage safe cities for women programme partners from using indicators based on women’s and girls’ experiences of violence – firsthand accounts are both useful and important because they provide women’s perspectives on the local situation.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a set of ethical and safety guidelines for researchers working with women who have experienced domestic violence that should always be used by researchers involved in a safe cities for women programme. When working with indicators that involve women’s and girls’ personal experiences of violence:

- The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a set of ethical and safety guidelines for researchers working with women who have experienced domestic violence that should always be used by researchers involved in a safe cities for women programme. When working with indicators that involve women’s and girls’ personal experiences of violence: The safety of respondents and the research team is paramount and should infuse all project decisions.

- Prevalence studies need to be methodologically sound and to build upon current research about how to minimize the underreporting of abuse and violence.

- Protecting confidentiality is essential to ensure both women’s safety and data quality.

- All research team members should be carefully selected and receive specialized training and ongoing support.

- The study design must include a number of actions aimed at reducing any possible distress caused to the participants due to the research.

- Field workers should be trained to refer women requesting assistance to available support. Where few resources exist, it may be necessary for the study to create short-term support mechanisms.

- Researchers and donors have an ethical obligation to help ensure that their findings are properly interpreted and used to advance policy and intervention development.

- Violence questions should be incorporated into surveys designed for other purposes only when ethical and methodological requirements can be met.

From World Health Organization (WHO). (1999). Putting Women’s Safety First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence against Women. Geneva: Global Program on Evidence for Health Policy, World Health Organization.

Resource:

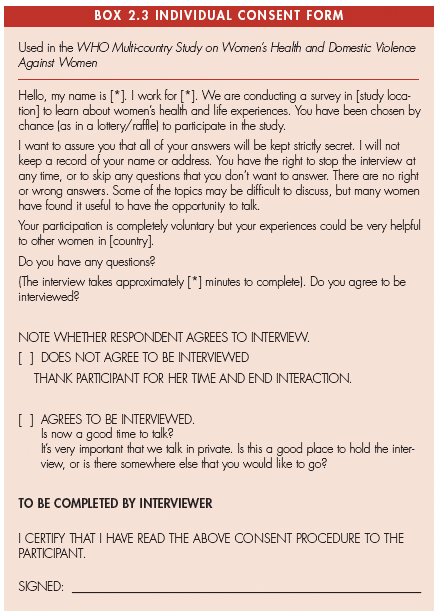

Individual Consent Form from WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women (2005). This example shows the kind of agreement any researcher must consider when using personal information from women and/or girls in her or his safe cities for women programme monitoring process.

Image Source: Ellsberg, M. and Heise, L.. 2005. Researching Violence against Women: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Activists. PATH and World Health Organization, Washington, DC, USA. Available online in English.

Define who is responsible for monitoring indicators.

Assign a person or people to regularly monitor indicators in order to see how safe cities for women actions are progressing. The responsibility of monitoring indicators includes collecting indicator data (Has the target been met?), comparing indicator data to other sources (Does the information provided make sense?), assessing what indicators mean (Is the project meeting its goals? Could certain things be improved?), and reporting indicator results to other programme partners so that everyone can learn about what works and what does not.

Record actions in a variety of different ways.

In addition to using indicators for monitoring, safe cities for women programme partners can collect and/or create other documents that will record the process of their actions, as they are happening; short progress reports are an example of this. These reports will enable programme partners to record different kinds of information about their process, which may be useful in the future (e.g., conflicting viewpoints, political challenges, ideas for new partnerships). The Raising Voices toolkit Mobilizing Communities to Prevent Domestic Violence: A Resource Guide for Organizations in East and Southern Africa provides the following suggestions on creating additional documentation for monitoring (pp. 73-74).

Examples:

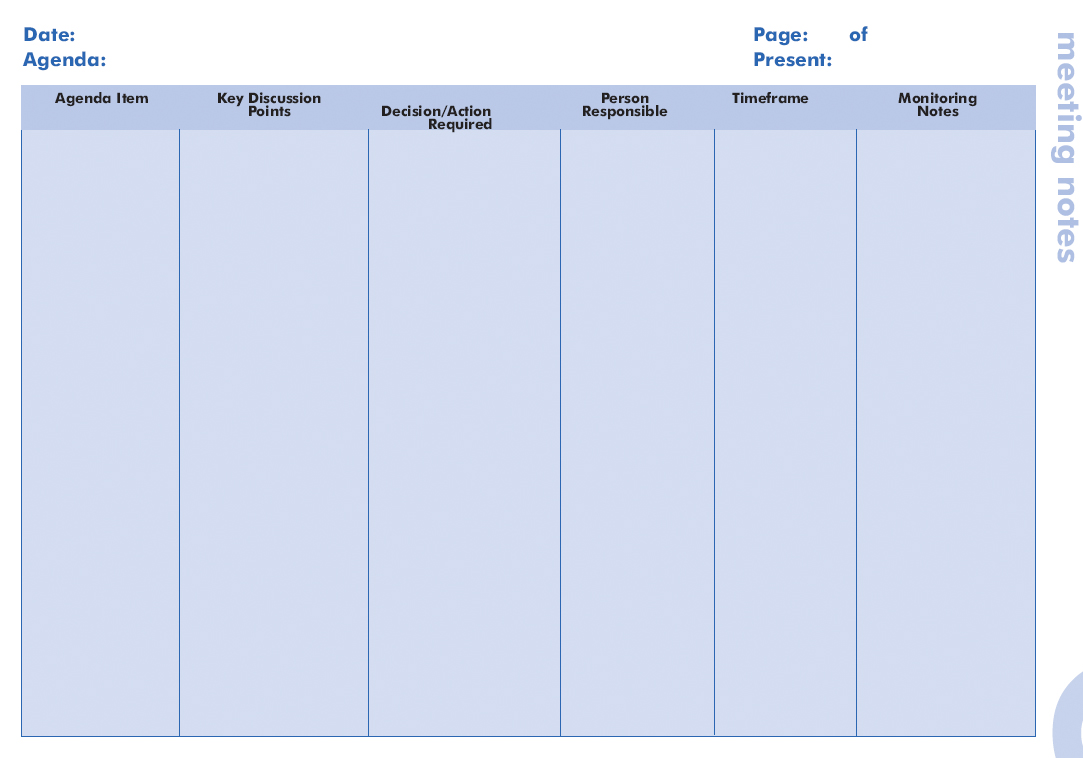

Meeting Notes: Meeting Notes document the weekly supervisory meetings held with each strategy department and help monitor progress and accountability.

Image Source: Michau, Lori and Dipak Naker. 2003. Mobilising Communities to Prevent Domestic Violence: A Resource Guide for Organizations in East and Southern Africa. Raising Voices, Kampala, Uganda. Available in English.

Image Source: Michau, Lori and Dipak Naker. 2003. Mobilising Communities to Prevent Domestic Violence: A Resource Guide for Organizations in East and Southern Africa. Raising Voices, Kampala, Uganda. Available in English.

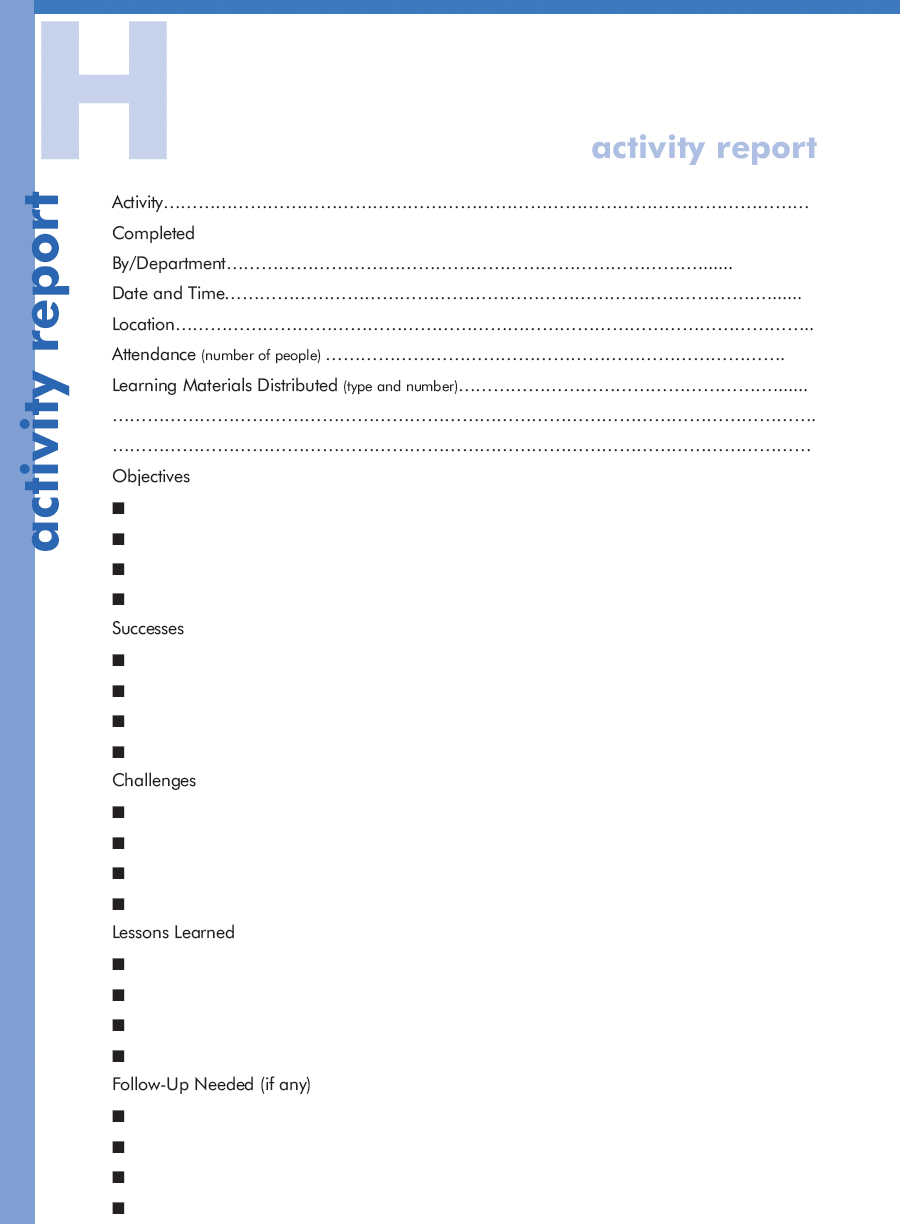

Activity Reports: Activity Reports are simple forms completed by staff members, resource persons, community volunteers, and other individuals conducting activities that track detailed information about each activity’s implementation, outcomes, and lessons learned.

Image Source: Michau, Lori and Dipak Naker. 2003. Mobilising Communities to Prevent Domestic Violence: A Resource Guide for Organizations in East and Southern Africa. Raising Voices, Kampala, Uganda. Available in English.

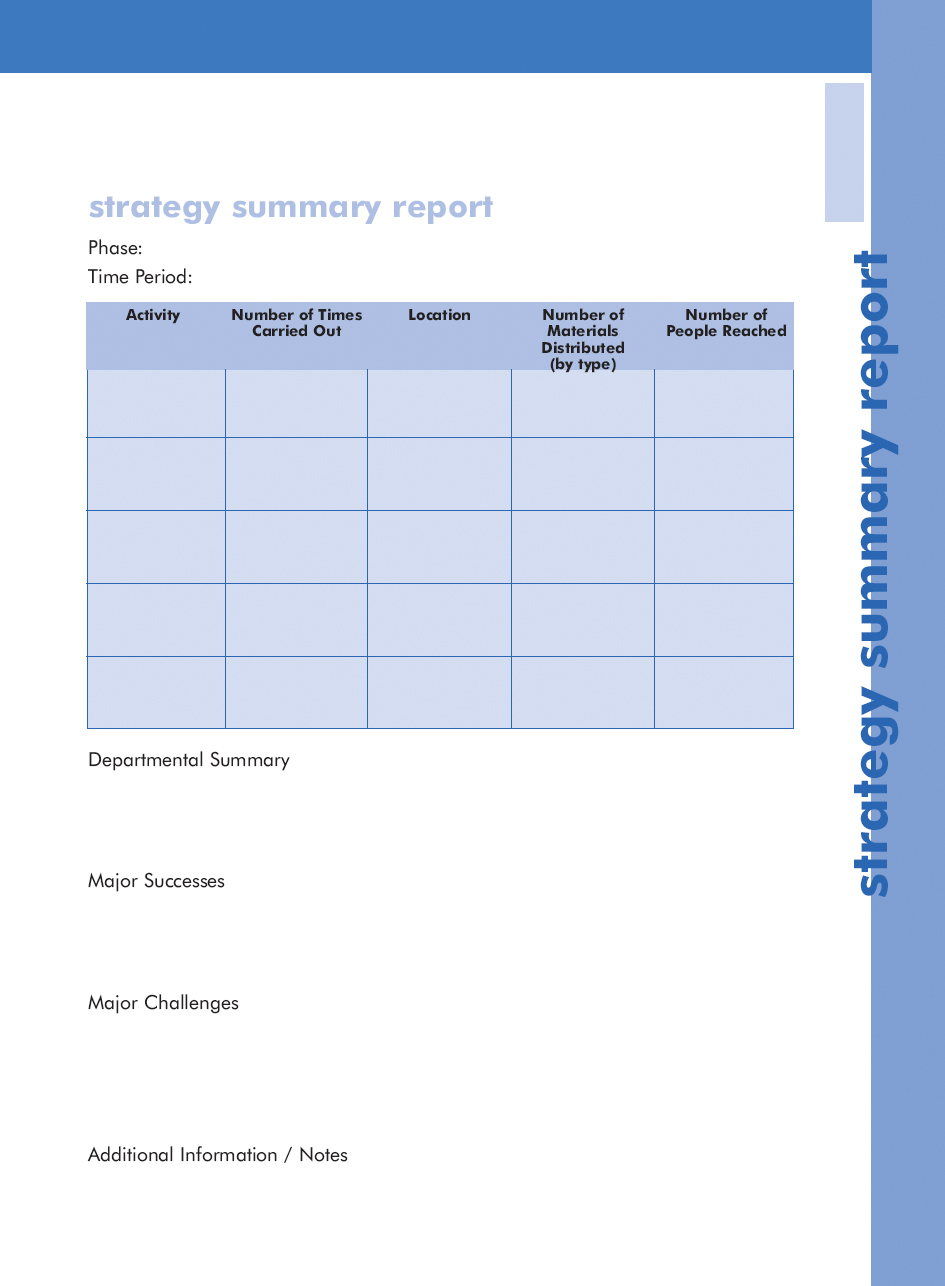

Strategy Summary Reports: The team or individual responsible for each strategy can write a Strategy Summary Report at the end of each phase. This report provides a summary of activities conducted, identifies successes and challenges, and proposes recommendations for the next phase.

Image Source: Michau, Lori and Dipak Naker. 2003. Mobilising Communities to Prevent Domestic Violence: A Resource Guide for Organizations in East and Southern Africa. Raising Voices, Kampala, Uganda. Available in English.

Phase Reports: Phase Reports document the lessons learned in each phase. Strategy Summary Reports can be compiled by the Project Coordinator to create an overall, narrative Phase Report. These reports are important in documenting the Project’s development.