In addition to design features and alternatives, the actual operations of the transit system should be adjusted to meet the needs of women and girls. These kinds of changes require that transit authorities prioritize gender concerns as they develop and improve their services. Therefore, these kinds of changes may take longer to be implemented than other kinds of programmes, such as Care Unit programmes.

EXAMPLE: Las Mujeres por una Ciudad sin Violencia (Women for a City without Violence), Colombia.

This short animated video demonstrates how thoughtful public transportation planning can help women access their cities more safely. This video could be used to advocate for everyday consideration of gender in public transportation planning activities. Available in Spanish

Adopt a Request Stop Programme.

Implementing a request stop programme is a great way for bus services to make transit safer and more convenient for women and other passengers. A request stop programme allows youth, elderly and female passengers travelling alone to request that bus drivers stop and let them off between bus stops. This allows passengers to walk shorter distances from the bus to their destination. Many cities implement this programme at night, when pedestrian routes are most isolated.

Case Study: The Request Stop Programmes in Toronto and Montreal.

Image Source: Toronto Transit Commission.

The Request Stop Programme was implemented in Toronto by the Toronto Transit Commission in 1991. This inspired the Montreal “Entre deux arrêts” (Between two stops) Programme, which was implemented by the Société de Transport de Montréal in 1996. Both programmes are ongoing and allow women and girls to request that bus drivers stop in between designated bus stops between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m, or after dark. This allows women and girls to travel shorter distances alone to their destinations at night. More information available in English or Montreal case study, in French and English.

Advocate for transport alternatives designed specifically to address the needs and safety of women and girls.

Affordable and safe alternatives to public transit should be made available to women and girls during times when service is not available or limited. This allows women to move around freely at off-peak hours. Mechanisms that could be put in place to accommodate such movement include rideshare programmes, specialized taxi programmes, community car rental programmes, and bicycle renting/sharing programmes.

Case Study: RightRides.

RightRides is a grassroots non-profit organization based in New York City that was founded in 2004. It provides free rides to women, transgender, and gender queer individuals on Saturday nights and early Sunday mornings (from 11:59 PM - 3 AM). Since 2004, RightRides has provided a safe ride home to almost 2000 people. The programme is run by volunteers using donated cars. RightRides also offers information and support to others wishing to start their own chapter (Reid, 2007). More information available in English.

Case Study: The “Wheel Trans” Service of the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC), Toronto, Canada.

Women in general face greater transportation barriers than their male counterparts. For women with disabilities, inadequacies in terms of reliable, safe and affordable public transit services are intensified by a lack of accessibility to existing services and a dearth of alternatives designed to respond specifically to the needs of the disabled. Furthermore, given that women with disabilities are more likely to experience abuse and violence, a lack of access to transportation can impede them from leaving abusive relationships. “Wheel-Trans” is a public transport service offered by the TTC to people with disabilities. The goal of this programme is to make conventional services and facilities available to disabled people, as well as to providing them with other, more specialized services. As a result, disabled women have access to reliable, safe and affordable transportation on a daily basis, as well as emergency transportation in the event that it is needed (Haniff-Cleofas and Khedr, 2005).

Promote concerted efforts to reduce overcrowding in streetcars, buses and trains.

Women and girls are more susceptible to insecurity when they are trapped on overcrowded transit cars (Kuneida and Gauthier, 2003, 10). Transit officials should make this problem a priority and work to lessen crowds through increased transit service at peak times, or the provision of women-only cars.

Consider the option of “women-only” vehicles, routes and time periods for subways, buses, trains and taxis when women cannot otherwise travel safely and when women themselves express the need and desire for this alternative.

Numerous versions of “women-only” programmes for subway, buses, trains and taxis have been adopted in cities such as Mexico City, Tokyo, Osaka, New Delhi, Lebanon and Rio de Janeiro. It is reported that as a result of these programmes, women and girls feel less threatened while on public transit and therefore more likely to use it. In spite of this advantage, “women-only” programmes also spark much public debate. There is concern that such measures will be considered by the public and decision-makers as a final solution, rather than as a temporary affirmative action meant to effect short-term change. The segregation of women does not ensure safe cities and communities. Rather, women and girls should be able to circulate safely through their environs anywhere and anytime, independent of whether men are present or not. Furthermore, it is feared that “women-only” approaches single out women, rather than targeting those who commit crimes (Loukaitou-Sideris et al. 2009, 47).

Nonetheless, the benefit of being able to commute to work without having to tolerate harassment, or take a taxi home without having to worry about where the driver might take you, is clearly important both in terms of creating safe alternatives for women and girls and increasing public awareness regarding the gender-specific barriers that plague public transit.

Image Source: Life

Image Source: Life

Examples:

The Tokyo Metro System.

Even though it is one of the largest and most efficient urban rail systems, the Tokyo metro is sometimes 200% over capacity. These crowded conditions foster an environment in which women are often harassed or touched by men. The existence of this type of violence led to the introduction of women-only carriages in the Kanto and Kansai areas. (Kuneida and Gauthier, 2003, 14).

Banet Taxi, Beirut, Lebanon.

Banet Taxi, which means “Girls’ Taxi” in Arabic, is a taxi service exclusively for women that started in March 2008. These pink taxis are driven solely by women and are meant to provide a safe, affordable alternative for women who are uncomfortable travelling alone in regular taxis and other forms of public transportation, especially at night. Prior to this “Pink Revolution”, such alternatives were completely lacking in Beirut (Duncan, 2009).

Image Source: Good.Is/Magazine

Forshe, New Delhi, India.

There are many barriers to women’s safe movement throughout the megalopolis of New Delhi: buses are infrequent, overcrowded and unsafe; the metro does not service the entire city; auto-rickshaws are not available at night and the railway system is a hotbed for harassment. Forshe, a radio taxi service exclusively for women, aims to counter these deficiencies by providing women with another choice: 24-hour taxis driven by women trained in the martial arts (Khullar, 2009).

Increase public transportation service based on women’s needs. In order to accommodate women and girls who tend to make trips with multiple stops throughout the day (for child/elder care, employment, shopping, etc.), it is recommended that public transportation systems increase their service during off-peak hours and offer more transit stops at regular times. In addition, attempts should be made to better connect destinations located outside of main commuting corridors, where women may travel for the multiple reasons mentioned above (Kuneida and Gauthier, 2003, 12).

Represent men and women equally among transit staff and public officials. A larger and more gender-mixed staff presence among transport officials may encourage women, girls and other people that experience harassment, abuse, robbery or any type of violent act to make a complaint. Likewise, the combination of more staff and the more equal representation of both women and men may help to deter violent acts in the first place. Thus, the presence of male and female staff on buses, subway cars, trains, and at stations should be promoted (Kuneida and Gauthier, 2003, 26).

Consider door-to-door safety.

Women’s and girls’ safety needs to be considered not only on public transit, but also travelling to and from public transit locations. Dangerous places en route to public transit could include dark streets, recessed doorways, dark spaces and deserted or abandoned buildings. Good lighting and landscaping are crucial on streets and around public transit terminals and stations. The promotion and development of mixed land uses is also a critical factor, as commercial spaces near to transit that are open consistently create a constant public presence (Kuneida and Gauthier, 2003, 26-27).

Case Study: Safe Women Project, New South Wales, Australia.

With the objective of promoting public responsibility for preventing sexual assault, the ‘Safe Women Project’ from New South Wales, Australia recommends that local councils adopt the following measures as a means to begin to “design out” sexual assault in public transit:

> Ensure that areas where people wait for public transport are well-lit.

>Ensure that main car parks are well-lit and supervised at night.

>Ensure all streets are well-lit - both in town centres and residential areas.

>Provide a walking path along main access routes which is well lit and has help access points.

>If the park cannot be supervised or made safe, then provide gates or turn off lighting to discourage users at night.

From Section 5 of Safe Women Project, Plan It Safe Kit (1998). Available in English.

Case Study: “Viajemos Seguras en el Transporte Público de la Ciudad” (Women Travelling Safely on the City’s Public Transit), Mexico City

History and Purpose of the Programme:

The programme, “Viajemos Seguras en el Transporte Público de la Cuidad” (`Women Travelling Safely on the City’s Public Transit, was initiated in 2007 as a collaborative effort between the Mexico City Metro and the Citizens’ Council for Public Safety and Legal Justice of Mexico City. Designed to integrate a gender perspective and coordinate institutional actions among all of the actors responsible for public safety in Mexico City, the programme’s objective is to guarantee that women travel safely and free from violence to and from their destinations.

Specific Objectives of the Programme:

- To strengthen public and institutional safety mechanisms that guarantee women’s protection, convenience and confidence while using public transit. This includes safeguarding their physical and sexual integrity.

- To promote respect for and the protection of women’s human rights through actions oriented towards prevention and dissemination of information.

- To foster a culture of denouncing violence, i.e. filing complaints for any type of aggression and sexual violence against women.

- To guarantee access to legal recourse and the sanction of perpetrators through expeditious, simple and effective proceedings.

The General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence

The General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence, enacted by the Mexico City Government on March 8, 2008, serves as an important framework for the Programme. The Law recognises the community as one of five realms where violence against women takes place. As defined by the Law, community violence is defined as those actions that are “committed against individuals or groups and which constitutes a threat to their safety and personal integrity and can occur in the neighbourhood, public spaces or spaces of communal use and free transit or on public property”. Article 23 of the Law specifies that the Public Transit System of Mexico City must create actions which address: prevention; identification of women who have experienced violence; research; public campaigns, among other items.

Strategic Lines of Action:

- The programme was designed to be implemented throughout Mexico City’s Public Transit System, with eventual coverage spanning all routes and lines, using three strategies that are coordinated inter-institutionally:

- The institution of subway cars, buses and other modes of transit designated exclusively for women. Currently, there are 67 women-only units serving 22 routes. From January until August 2008, 4 000 000 female passengers made use of this service.

- A programme for the separation of women and men transit users during peak hours. “Women Travelling Safely” Care Units: the installation of five Care Units for women who have experienced violence.

- Other initiatives that have been implemented as part of this programme include: the dissemination of information on sexual assailants on public transit; an increase of female police officers; and training for public officials, public transit authorities, police, public transit employees and operators, relevant public institutions and programme actors.

“Women Travelling Safely” Care Units

The five “Women Travelling Safely” Care Units are open from 8 a.m. until 8 p.m., Monday to Friday, and have women lawyers from the Instituto de las Mujeres de la Ciudad de Mexico – Inmujeres DF (Women’s Institute of Mexico City) on staff. The Care Units provide women with the following services:

First response to women who have experienced some form of sexual crime upon their arrival.

>Legal advice from the lawyers from Inmujeres DF.

>Referral to the appropriate legal authority.

>Transportation to the appropriate legal authorities.

>Accompaniment through the entire process of initiating a complaint.

>Follow up on the verdict by a lawyer from Inmujeres DF and by the Citizens’ Council for Public Safety and Legal Justice of Mexico City.

>Written and verbal provision of basic information.

>Advice for women who visit the Care Unit for other materials, as well as links and/or referrals to competent entities.

From Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres México; Inmujeres DF (Women’s Institute of Mexico City). (2008). Powerpoint Presentation - Viajemos Seguras en el Transporte Público de la Ciudad (Women Travelling Safety on the City’s Public Transit). Available in Spanish.

Advocate for gendered safety considerations as important issues that complement and do not detract from other transit concerns.

Efforts to promote successful policies and programmes should take into account that because public transit is a service funded by the government, it is an inherently political topic that inspires public debate. Safe cities for women programme partners should work together to ensure that public transit resources are spent in ways that promote the needs and rights of women and girls, while pointing out the benefits for all (i.e. improving the reliability of local bus service will not only benefit women, but also all bus users). Moreover, increasing the reliability of bus services will likely lead to increased ridership, which will result in financial and environmental benefits for the whole community.

Coordinate all actions related to safe public transit initiatives.

It is important that community groups, local governments, and public transit actors not only participate in, but also coordinate actions for safety. Coordination is necessary in order for planning, policy and design decisions to work together towards the larger goal of women’s safety. Without coordination, actions may be duplicated needlessly or may cancel each other out. Some of the key individual and institutional actors who should coordinate their actions include: police, public safety groups, justice departments, public transit authorities, women’s organizations, urban planning departments, private architects and community organizations (Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres México; Inmujeres DF (Women’s Institute of Mexico City, 2008).

Case Study: Perspectiva de género en el plan de transporte comarcal (A Gender Perspective in the Regional Transportation Plan), Pamplona, Spain.

The objective of this initiative, which was included as a priority issue in Pamplona’s Equality Plan drafted for the Office of Urban Affairs, is to incorporate a gender perspective in the design of the city and its urban development projects. A goal of this initiative was the creation of projects and plans that are better adapted to the needs of all citizens, thereby improving the quality of life in the city. The initiative was based on research regarding women’s specific transportation/mobility needs in different neighbourhoods of Pamplona and Comarca. Proposals for design and planning were developed according to the following axes: connections between neighbourhoods, transit lines and routes, frequency of transit, the design of buses, the design of bus stops, payment systems and organizational culture. Every phase of this process was informed by the participation and input of a diverse cross-section of women living in, working in and using the two cities. Taken directly from Moya, A. (2000). “Perspectiva de género en el plan de transporte comarcal, Pamplona (España) ». In CIUDADES PARA UN FUTURO MÁS SOSTENIBLE.

Emphasise the need for improved data collection on women’s use of public transit.

Quality household and user surveys, with separate data on women and men, are needed to determine when and where women and girls use public transit. This is important because this information can be used to determine what factors encourage or discourage women and girls from using public transit. These surveys should take into account the complex constraints (e.g. lack of money) and unmet demands (lack of nearby grocery stores) that women and girls must face when travelling in the city. Sometimes, the routes women and girls take, and the reasons for these routes, are too complex to be recorded on a standardized survey response sheet. In such cases, open-ended interviews or focus groups might be a better data collection option. In fact, many deeply-embedded cultural, social, and mobility constraints can only be revealed through interviews and conversations (Peters, 2002, 18). In general, more research on the intersection between gender, transport and mobility is essential (Peters, 2002, 3). For more information on collecting data about women’s use of space, see the section on identifying safety problems for women and girls.

Resources:

Gender and Transport Resource Guide (World Bank, 2006). This online tool constitutes a thorough guide on how to research gender mainstreaming in transport policies and plans. It is comprised of six modules: 1) Why Gender and Transport? 2) Challenges for Mainstreaming Gender in Transport, 3) Promising Approaches for Mainstreaming Gender in Transport, 4) Gender and Rural Transport Initiative (GRTI), 5) Tools for Mainstreaming Gender in Transport, and 6) Resources for Mainstreaming Gender in Transport. Each module offers a combination of checklists, training manuals, reports and slide presentations, and case studies and best practices from around the world that can be used in the design and planning process, research, capacity building initiatives, advocacy work, and more. The guide provides useful analysis regarding the intersection of gender, transport and poverty and considers both rural and urban contexts. Available in English.

How to Ease Women’s Fear of Transportation Environments: Case Studies and Best Practices (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2009). Mineta Transportation Institute, USA. This paper provides rich information on the intersections between gender, transport, mobility and violence. The authors examine numerous case studies on the implementation of gendered strategies in public transit, such as women-only transportation vehicles. The authors also document the findings from qualitative interviews with women regarding their fears in public transit settings, the kinds of public transit settings which produce fear, behavioural adjustments to cope with fear, and the distinct needs of women. Suggested actions and policies, design strategies and security technology are also addressed. Available in English.

Produce and distribute materials about safety to public transit users.

Materials such as flyers, posters, stickers, and newsletters can be distributed on and around public transit. These materials could include safety strategies for women and girls to use while travelling, information on where to report sexual harassment or where to call for emergency assistance, or information about legal or policy provisions against these forms of gender-based violence. They could also include information on programmes already in place to improve public transit for women and girls. The process of distributing materials raises awareness about women’s and girls’ needs on public transit (Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres México; Inmujeres DF (Women’s Institute of Mexico City), 2008). For more information see the raising awareness section.

Examples:

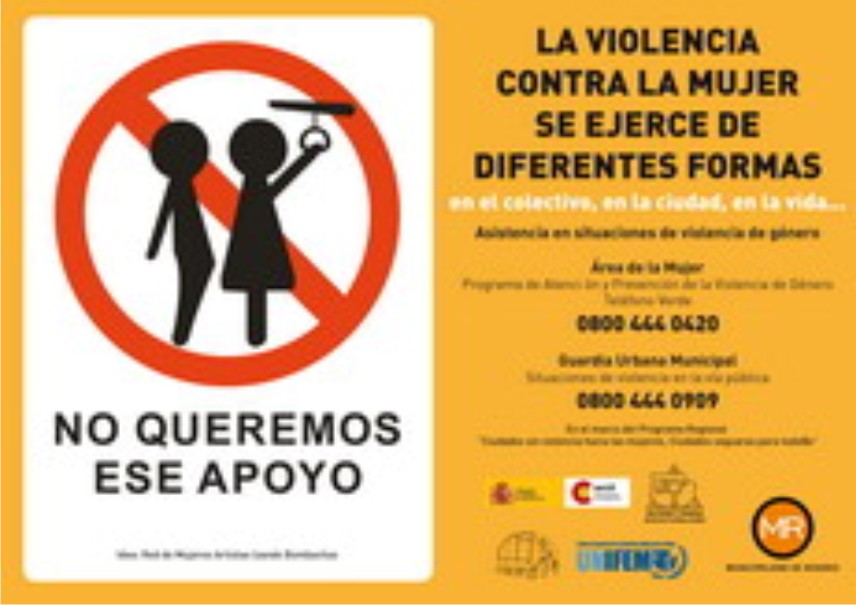

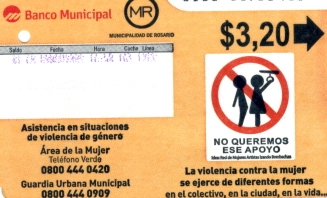

No queremos ese apoyo (We don’t want that kind of support) campaign, Rosario, Argentina.

In 2008, the No queremos ese apoyo (We don’t want that kind of support) campaign was launched on public transit in Rosario, Argentina by the Regional Program "Cities without violence against women, safe cities for all". The purpose of the campaign was to raise awareness about women’s experiences of sexual harassment on transit and to ensure that public transit users understood that sexual harassment was unacceptable. Posters with the campaign logo were placed inside transit vehicles. Posters also featured information and telephone numbers that passengers could call to make complaints or ask for further information. The campaign logo was also featured on bus tickets that were printed and used all over the city.

Image source: Boston.com

Anti-harassment posters on Boston Subway.

On the Boston subway system, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority released a series of posters which encourage women to report incidences of harassment on public transit. As a result of the campaign, the number of groping complaints in the city increased by 74 per cent (Boston Globe, 2009).

See message stickers displayed on public transit in New York City, United States from: Transit Blogger

Ensure that training and capacity development on gender-specific issues is provided for public officials and public transit staff, including safety personnel, planners and drivers.

When public transit staff are trained about women’s and girls’ safety, they are better able to identify and fix safety problems within the transit system, and more likely to be responsive to women and girls who seek their help. Finally, given public transit in many places is a male-dominated occupation, men staff should receive tailored sensitisation aimed at transforming traditional notions of gender roles and masculinities LINK to transform harmful and unhelpful attitudes. For more information on training public transit staff, see the capacity development section.