- In many countries, a majority of disputes are dealt with through a variety of non-state, traditional, customary, religious and informal systems, and alternative dispute resolution systems. Estimates suggest that in many developing countries approximately 80% of cases are resolved through such mechanisms (UN Rule of Law website and Governance and Social Development Resource Centre (GSDRC) “Non-state justice and security systems”). As a result, strengthening the legal/justice sector in post-conflict settings means not only working with the formal justice systems but also working with non-state justice systems to end impunity and promote long-term peace and stability. It is important to explore and respond to the expressed needs of survivors in developing justice responses—in some cases, survivors may wish to access non-formal justice structures, but it is critical that these structures are designed in such as way as to limit the risk of stigmatization and/or harm to survivors.

- These non-state justice systems often take place at the community level and derive their authority from community structures and social groups. They do not necessarily distinguish between criminal and civil wrongs; they come into play when a wrong of any sort is committed that disrupts the social order in the community (UNODC and United States Institute of Peace, 2011; UNODC. 2010; UNWOMEN, 2011). Leaders who are governed by religious, cultural, and/or tribal practices make the decisions.

- In post-conflict settings (including IDP areas and refugee camps) VAWG crimes are habitually dealt with through these non-state justice systems because it is often the only form of justice available. Even in non-conflict settings, the WHO multi-country study on domestic violence against women found an estimated 60-90% of survivors never sought help from any formal institution after the assault (WHO, 2005). Survivors are much more likely to approach informal channels for support, and depending on what response they receive, may never reach out again for support. While there are often significant challenges in securing justice for survivors through traditional mechanisms, in many contexts they are a reality to be addressed, and in some conflict-affect settings may be easier to influence (in terms of building support for survivors-centered approaches) than the formal justice sector. Restorative justice techniques for domestic violence have begun to be explored as supplementary systems to work alongside the legal justice sector.

- Any decisions about working through mediation and other restorative justice mechanisms must consider the frequent failure of these systems to actually stop the violence the survivor is experiencing, in part due to:

- Victim blaming and other attitudes on the part of traditional mediators or participants in the traditional justice mechanism;

- Incorrect assumptions for joint responsibility for the violence in many traditional mediation techniques (i.e. each side gives up something to meet in the middle), which are not appropriate for domestic violence dynamics;

- Incorrect assumptions that the survivor and perpetrator have equal power to create change and express the problem;

- The potential for reconciliatory forms of restorative justice to play into the “sorry phase” of the cycle of violence, making the survivor vulnerable to further violence

- Risk of women giving up their individual rights so as to preserve harmony within a social group.

- The failure of many forms of mediation to address the root cause of the violence as the power imbalance between women and men in the community and the couple, focusing instead on an incident that triggered a particular episode of violence.

- Nevertheless, and especially in cultures with strong traditions of restorative justice, there may be benefits to working with and through these systems:

- Greater cultural appropriateness of some restorative justice models,

- Examples of success of these mechanisms holding perpetrators responsible for the violence,

- Community support for proposed solutions,

- Far greater accessibility of the systems to survivors, particularly during conflict and post conflict-settings,

- The absence of access to formal justice mechanisms,

- The lack of women’s economic empowerment and alternative safe housing in most areas that would allow survivors the possibility to cut relations with the perpetrator without some form of agreed upon community support, and

- The fact that mediation is still used by many police officers, social service agencies, non-governmental organizations, elders, and other community-based, informal referral points for cases of domestic violence—whether survivor advocates agree with it or not.

- Non-state justice systems may be preferred because they can be:

- less costly

- quick and convenient

- familiar to local populations

- culturally relevant

- responsive to poor people’s concerns (DFID, 2004).

- Alternative forms of justice resolution can complement both the formal and non-state legal systems since they can provide a basis for the informal resolution of civil matters and minor offences at the community level. They can also be a way to ensure that traditional and valuable restorative justice practices are not lost to the increasing influence of retributive forms of punishment.

- Traditional leaders can be important allies: as “custodians of culture” they have the authority to positively influence a change in customs and traditions in favor of those that uphold women’s rights (DFID, 2012, p. 26). Outlawing VAWG-related non-state justice mechanisms without public education and awareness is the least effective means of reform in the informal sector. Changing the law in combination with ongoing education and provision of alternatives is a preferable strategy. It is therefore important to work with these systems and make them more gender-responsive by building their capacity to incorporate international human rights standards and increase the choices available to women who are seeking remedy outside state justice systems.

- Key strategies to improve non-state justice mechanisms should aim to identify and build on the strength of the systems and include:

- increasing the participation of women in the mechanisms,

- providing comprehensive training to all participants in the mechanisms

- increasing and strengthening non-governmental organization’s engagement with non-state mechanisms to alter power inequities,

- changing the types of remedies that are proscribed through non-state systems,

- creating entirely new justice mechanisms,

- improving links with the formal justice system (UNODC and United States Institute of Peace, 2011; UNODC, 2010).

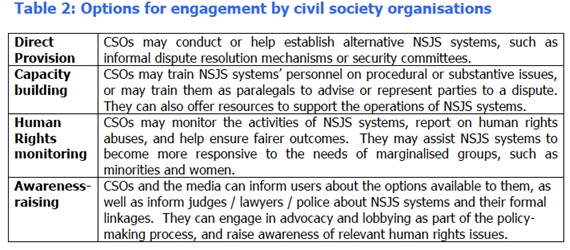

- The table below presents illustrative examples of strategies to work with non-state justice and security systems (“NSJS”). These strategies should be explored alongside other innovative strategies, complemented with strong monitoring and evaluation. Strategies should also be undertaken with wider community engagement, rather than limiting work to CSOs dedicated to non-state justice and security systems.

Source: DFID. 2004. Non-state Justice and Security Systems. Briefing Note p.12.

Source: DFID. 2004. Non-state Justice and Security Systems. Briefing Note p.12.

- While there have been many attempts to engage traditional and local justice mechanisms in order to maximize benefits and minimize negative and/or dangerous consequences, there has been a dearth of formal evaluations of these interventions. Evaluations of and information sharing between creative restorative justice interventions that have strong monitoring mechanisms—ones that have procedures in place to stop the intervention if it should be found to put the survivor in danger--should be encouraged and shared widely.

For more information and a detailed list of strategies, see the informal justice mechanisms section of the Justice Module.

Additional Tool:

Handbook on Restorative Justice Programmes (UNODC, 2006). This is one in a series of handbooks created by UNODC. It provides an overview of restorative justice concepts and focuses on a range of programmes (including case studies) that provide a more participatory approach to criminal justice. Available in English and French.

Additional Resources

Sharing Experience in Access to Justice: Engaging with Non-State Justice Systems and Conducting Assessments (UNDP, 2012). Available in English.

Here to Stay: Traditional Leaders’ Role in Justice and Crime Prevention (Tshehla, B./SA Crime Quartlery 11: 15-20, 2005). Available in English.

Restorative Justice in Post-war Contexts (Stovel, L./paper presented at the Restorative justice conference, Vancouver, June 1-4, 2003). Available in English.

Rule of Law Reform in Post-Conflict Countries. Operational Initiatives and Lessons Learnt (Samuels, K. Social Development Papers. Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction, Paper No. 37/ October 2006). Available in English.