- To improve service delivery to victims of VAWG, the justice/legal sector should ensure the following:

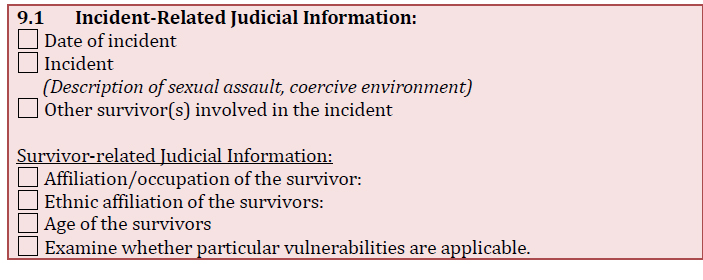

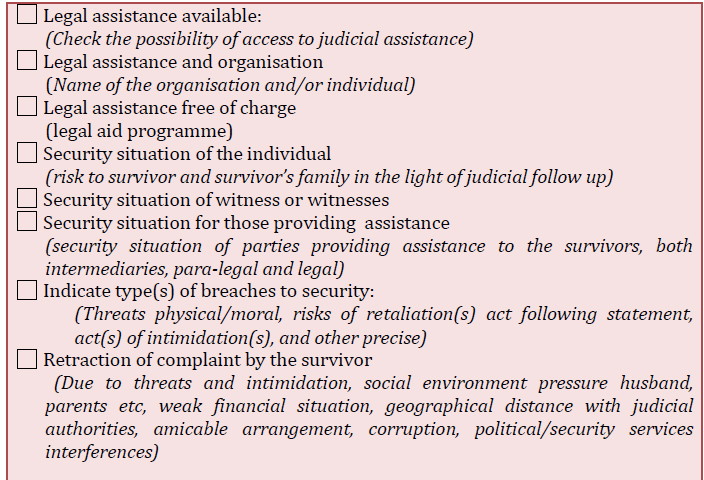

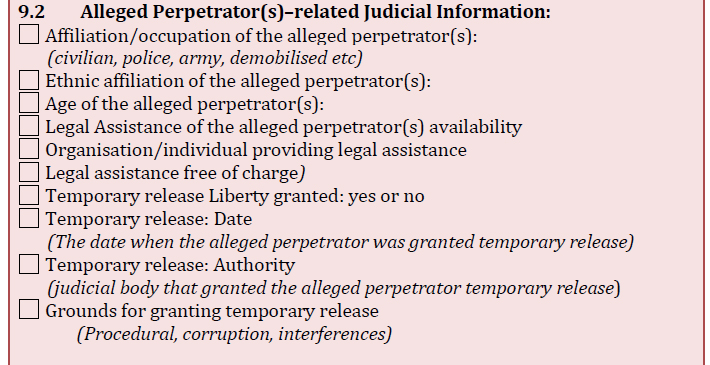

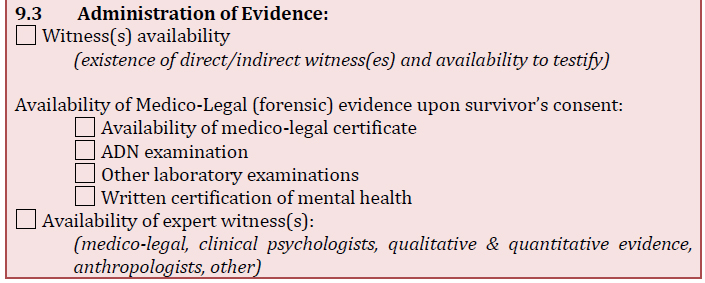

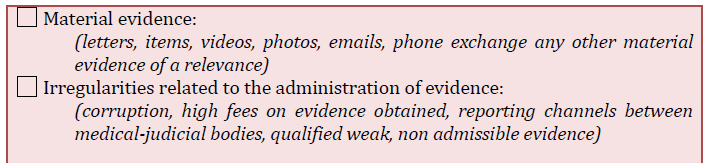

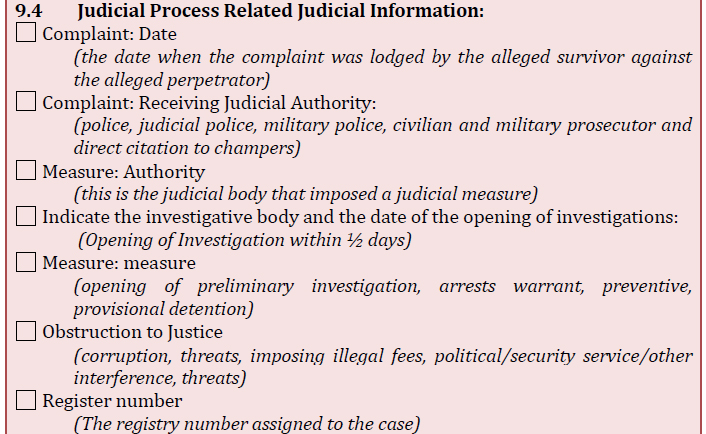

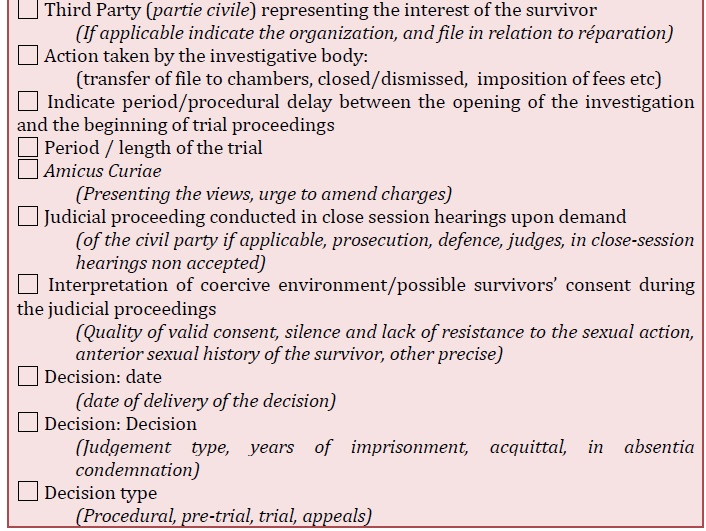

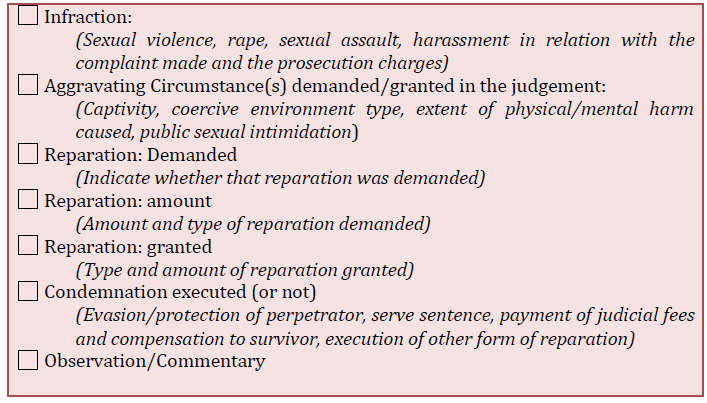

1. Develop and implement gender-responsive standards, procedures and checklists to ensure confidentiality and proper documentation of cases. The following checklist provides a practical example on issues related to facilitating access to justice for victims of sexual violence.

2. Ensure that the response is survivor-centered and occurs in an environment that promotes the dignity of the survivor and ensures her physical and emotional safety. Support services should be made available, such as referrals, childcare support, translation and access to staff knowledgeable about and sensitized to diverse populations and VAWG issues.

3. Make justice affordable.

- Establish and expand legal assistance programmes for women and girls order to ensure that free or low-cost legal counseling and representation is available to survivors of VAWG (for more information see Justice Module).

- Consider fee waivers and reductions.

- Review costs associated for making a claim, including both “direct” (fees that must be paid to use the justice institution such as a charge to file a case, or a bribe), and “opportunity” (the income that a person can lose bringing a case to justice) costs. Work to find innovative ways to decrease or eliminate these costs (American Bar Association, 2012).

4. Ensure that victims of VAWG have physical access to state and non-state justice institutions. The further a victim has to travel to seek assistance, the less likely it is that they will lay a claim (American Bar Association, 2012).

- Support the establishment of justice institutions in remote areas where survivors might not otherwise have access to justice (UN WOMEN, 2011). Consider supporting the establishment of mobile or traveling courts for rural and remote areas. (For more information on mobile courts see Improve physical access to justice for women and girls.)

- Ensure buildings are physically accessible to women and girls with disabilities (Human Rights Watch, 2012).

- Consider specialized courts for violence against women and girls.

- Use civic education programs to combat fear of public institutions and negative attitudes.

- Support court accompaniment programmes involving trained advocates to assist victims in accessing courts and understanding rules and procedures.

- Address other issues that might impact accessibility include the transportation infrastructure, insecurity and restrictions on travel, and the threatening nature of the legal/justice system (American Bar Association, 2012).

5. Work to improve the timely resolution of cases.

- Support efforts to lower caseloads and improved case management procedures (American Bar Association, 2012).

- Increase training of and use of paralegal personnel to assist victims. (See Service delivery and access).

6. Increase community mobilization in defense of women’s rights.

- Community support for survivors VAWG and collaboration with justice mechanisms is an important part of the justice sector’s response to VAWG. In particular, communities can play a crucial role by recognizing and promoting women’s right to a life free of violence, and by providing community support to women seeking justice through the formal or informal system (Bott ,Ellsberg and Morrison. 2004). Strategies to increase community mobilization include ( excerpted from Bott, Ellsberg and Morrison, 2004, unless otherwise noted):

- Provide legal literacy training for key groups and stakeholders

- Support NGOs who provide legal aid and social/psychological services

- Include civil society participation in efforts to monitor the justice system

- Raise awareness of and build support for new/revised legislation among the general population using culturally appropriate methods tailored to communities, such as radio programmes, drama and dramatization, and IEC materials

- Support human rights promoters and community based paralegals who play a key role in ensuring that survivors know their rights, can access the formal system, and are able to negotiate both formal and informal plural legal avenues (DFID, 2012). (Also see JUSTICE MODULE)

- Strengthen non-state justice mechanisms and community-based alternative resolution, where appropriate.

Case Study: Access to Justice for Refugee Women and Girls in Tanzania. From 2008-11, the Women’s Legal Aid Centre (WLAC) implemented a project in Mtabila and Nyarugusu refugee camps in western Tanzania. The project assisted refugee women and girls to access justice and strengthened the capacity of refugee communities to respond to high rates of violence against women and girls. WLAC educates women refugees about their rights and supports them to claim them through legal assistance and counselling. The project worked at several different levels:

- Establishing paralegal units in the camps and training refugee paralegals to provide free legal aid services to survivors of violence.

- Provision of legal and human rights education for refugees via dissemination of educational materials, use of drama and folk music, and radio programmes on refugee rights with information on where and how to access justice.

- Roundtable discussions with community leaders.

- Building the capacity of law enforcers to respond to violence against women and girls including police, immigration officers, social welfare and community development officers, magistrates and camp settlement officers.

- Working with a refugee police force, elected by refugees. WLAC trained refugee police in Tanzanian law and women’s rights, and linked them up with paralegals who provided legal advice and support.

- Working with host communities to encourage them to respect the rights of refugees.

The baseline survey conducted by WLAC showed women were reluctant to report violence against women and girls cases because police referred the cases back to be handled by families. It also showed that women were discouraged by the community from reporting cases. The final evaluation report revealed significant changes:

- Refugee communities have become vigilant on violence against women and girls issues and rally behind women who seek justice after experiencing violence. Community leaders and others in the community accompany women to report violence and are no longer ashamed to associate with them.

- Camp Leaders and Local Tribunal members who administer customary laws in the camps now refer violence against women and girls cases to the police, WLAC or paralegals rather than handling them themselves.

- Refugees, particularly women and girls, have more knowledge about their rights and are accessing them. There has been an increase in the number of cases reported to the police –from a negligible number prior to 2008, to 400-500 cases a year by 2011.

- Women report being taken more seriously by the police and there have been successful cases where perpetrators have been convicted

See the training materials.

(adapted from DFID, 2012, pgs. 24-25).