- Conflict-related violence against women and girls has been referred to as “one of history’s great silences” (Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, 2005, cited in Ward, 2005, p 67). Although overall more men than women are killed in armed conflict, women and girls are disproportionately affected by particular types of violence, such as sexual and gender-based violence, and other consequences of war, including displacement and loss of livelihood.

- Over the last twenty years, there has been growing concern among humanitarian aid organizations and within peacekeeping operations about the extent and effects of VAWG in conflict-affected settings. There has also been increasing recognition that VAWG has lasting negative impacts on individuals and communities, and severely undermines universally accepted human rights and protection guarantees that are the foundation of humanitarian intervention.

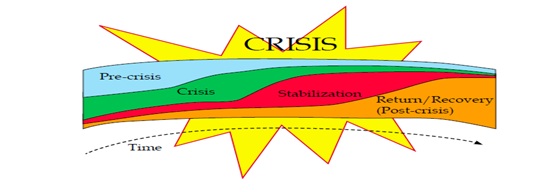

- When considering the problem of VAWG in conflict-affected settings, the focus is often on violence during the conflict. However, literature on emergencies usually takes into account a much broader time frame for humanitarian response, sometimes referring to the phases of an emergency as pre-crisis (before disaster strikes); crisis (when the disaster strikes and/or is at its zenith, often resulting in significant displacement); stabilization (when immediate emergency needs have been addressed); and return/recovery (when those who are displaced are returning home and/or the focus is on rebuilding systems and structures and transitioning to development). It is important to understand that all these stages are fluid; they overlap; and that it is possible to move backwards along this continuum (such that, for example, a relatively stable setting can lapse into periodic conflict). Thus, work during each phase often involves planning for other phases.

Visual from CARE, “Building Partnerships for Health in Conflict-affected Settings”, May 2007, pp 9-10.

- Any comprehensive VAWG prevention and response framework should consider all stages of humanitarian interventions, and attempt to prioritize programming accordingly (for more information about VAWG prevention and response according to different phases of conflict, see Section IV, VII and VIII). The following table presents an overview of different types of violence that may emerge in different phases of conflict. This list is illustrative, and can vary considerably according to context.

|

Phase |

Type of Violence |

|

During conflict, prior to flight |

Rape as a tool of war; Sexual attack/exploitation by combatants and community members; Forced prostitution; Increased domestic violence; Trafficking; Female infanticide; Early and/or forced marriage |

|

During flight |

Sexual attack/exploitation by bandits, border guards, military; Trafficking; Forced prostitution |

|

In the country of asylum |

Sexual attack/exploitation by persons in authority including camp representatives, host country officials (i.e. police officers), humanitarian workers, foster care families; Domestic violence; Sexual attack when collecting wood, water, etc t Early/forced marriage; Trafficking; Sex for survival (ration cards, clothing, etc.) |

|

During repatriation |

Sexual attack/exploitation of women and girls who have been separated from family; Sexual attack/exploitation by persons in power, including government officials and humanitarian workers; Sexual attack/exploitation by bandits, border guards, military |

|

During reintegration, post-conflict |

Returnees may suffer sexual attack as retribution; Trafficking Domestic violence; Sexual exploitation |

Source: Adapted from UNFPA, Curriculum Guide for Managing Gender-based Violence Programmes in Humanitarian Settings, 2011.

- Reliable prevalence data on the scope of different types of VAWG in different phases of conflict is difficult to obtain. Even so, a small but growing body of evidence is bringing to light the scope of the problem.

-

- A 2010 prevalence study in Eastern DRC assessed that nearly 40 percent of women were survivors of sexual violence.

- In the Colombian conflict, according to the government’s Victims Unit, indigenous and afro-Colombian women are disproportionately targeted for attacks: 76% of homicides of indigenous people and 66% of black/afro-Colombian homicides are women.

- An estimated 20,000 to 50,000 women were raped during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the early 1990s.

- The vast majority of Tutsi women in Rwanda’s 1994 genocide were likely exposed to some form of sexual violence; of those, it is estimated that a quarter to a half million survived rape.

- Approximately 50,000 to 64,000 of women who were internally displaced during Sierra Leone’s conflict reported histories of war-related assault.

- In a 1995 survey of post-conflict Nicaragua, 50 percent of female respondents had been beaten by a husband, and 30 percent had been forced to have sex.

- 66.7 percent of participants in a 1998 Sierra Leone survey on domestic violence had been beaten by an intimate partner

- According to a 1999 government survey, 37 percent of Sierra Leone’s prostitutes were less than 15 years of age, and more than 80 percent were unaccompanied or displaced children.

- Research undertaken by the Human Rights Documentation Unit and the Burmese Women’s Union in 2000 concluded that an estimated forty thousand Burmese women are trafficked each year into Thailand’s factories, brothels, and as domestic workers.

- Findings from a 1999 study of Palestinian refugee women indicated 29.6% of women were subjected to beating at least once during their marriage with the husband the main perpetrator and 67.9% of children had been beaten at least once almost entirely by their parents.

- 25 percent of Azeri women surveyed in 2000 by the Centers for Disease Control acknowledged being forced to have sex: those at greatest risk were among Azerbaijan’s internally displaced, 23 percent of whom acknowledged being beaten by a husband.

- Thousands of Congolese girls and women suffer from tissue tears in the vagina, bladder and rectum, after surviving brutal rapes in which guns and branches were used to violate them. A survey of rape survivors in South Kivu region revealed that 91% suffered from one or several rape-related illnesses.

- In 2003, 74% of a sample of 388 Liberian refugee women living in camps in Sierra Leone reported being sexually abused prior to being displaced. 55% experienced sexual violence during displacement.

(Data compiled from IRIN, “Broken Bodies, Broken Dreams: Violence Against Women Exposed”, 2006, and “The Shame of War”, 2008; UNFPA, Curriculum Guide for Managing Gender-based Violence Programmes, 2011.)

- One challenge in understanding the full extent of the problem of violence against women and girls in conflict-affected settings is that the majority of incidents of VAWG are likely to go unreported in emergencies, not only because of the high levels of stigma that commonly accompany these crimes, but also because of the lack of health and other services during and directly following a crisis.

- Furthermore, conflict-affected settings that lack reliable statistics as well as systems to collect them periodically, or even the safety and necessary infrastructure to conduct one-time data collection exercises, such as population-based household surveys. Population displacement and return render previous census data and household surveys, if they exist, meaningless, and undermine the ability to obtain a random sampling for the administration of new surveys. Police records suffer from information gaps, filing mistakes, and unusable taxonomies. The judicial institutions are too weak or devastated by war to keep track of the percentage of cases of gender-based violence investigated, transferred to court, prosecuted, and resolved. This is all compounded by the common logistical challenges of simply moving around in these countries, and the long periods of time in which entire regions are completely inaccessible due to weather or insecurity.

- Obtaining specific data on the prevalence of sexual or other forms of violence should not be a priority at the onset of an emergency. Because of the high level of under-reporting and the security risks associated with obtaining data, the priority is to establish prevention and response measures as soon as possible. (For more information on researching violence against women, see Section VI information on conducting assessments on VAWG in humanitarian settings.)

Additional Resources

International Committee of the Red Cross. 2001. ‘Women Facing War’, ICRC, Geneva. Available in English.

UNIFEM, 2002. Women, War and Peace. Available in English.

OCHA/IRIN, 2005. Broken Bodies, Broken Dreams: Violence Against Women Exposed. See Chapter 13 on sexual violence in conflict. Available in English.

Vlachova, M. and Biason, L. (eds), 2005. Women in an Insecure World: Violence against Women Facts, Figures and Analysis (DCAF). Available in English.

USAID, 2006. “Understanding the Issue: An Annotated Bibliography on GBV”. Available in English.

Ward, J., “Gender-based Violence in Refugee, Internally Displaced and Post-Conflict Settings: A Global Overview” (RHRC, 2002). Available in English.

Vann, B., “Gender-based Violence: Emerging Issues in Programs Serving Displaced Populations” (JSI/RHRC, 2002). Available in English.

Stark, L. & Ager, A. 2011. A Systematic Review of Prevalence Studies of Gender-Based Violence in Complex Emergencies. Trauma, Violence & Abuse,12(3)127-134. Available in English.

Heineman, Elizabeth D. (ed.), 2011. Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones from the Ancient World to the Era of Human Rights, A volume in the Pennsylvania Studies in Human Rights Series. Available in English.

International Rescue Committee. 2010. “Let me not die before my time: Domestic Violence in West Africa”. Available in English.

ACCORD. 2012. An overview of the situation of women in conflict and post-conflict Africa. Available in English.