Shelters assisting women and girl survivors or at risk of harmful practices, such as forced marriage, female genital mutilation, and crimes committed in the name of ‘honour’ must consider the specific circumstances related to each form of violence and tailor their practices regarding the provision of safe emergency and longer-term accommodation, legal, financial and psychosocial supports accordingly.

Forced marriage

Women and girls fleeing forced marriage often experience a range of specific challenges to receiving assistance, in additional to general barriers to help-seeking. These challenges include:

- Lack of legal protection from forced marriage. While international and regional agreements establish protections against forced marriage, many countries do not have comprehensive laws and policies to protect and assist young women threatened with a forced marriage or victims of forced marriage. This creates particular challenges for minors who seek shelter assistance, who may be unable to access legal protection from social service agencies and are returned to their families, further increasing their risk of abuse. See specific guidance on forced marriage legislation.

- Heightened risks associated with disclosure. For example, young women may receive threats or be at-risk of violence (e.g. honour-related crimes) if their families learn of their efforts to seek help. Parents may threaten to marry a younger sibling if the girl doesn’t submit to the forced marriage. Concerns over their families being deported or other immigration-related fears may also prevent girls to seek support. In small communities or areas where access to services may be limited or confidentially cannot be guaranteed, these issues may be of even greater concern.

- Perceptions that the forced marriage is not a form of violence and is a norm within their family or community, reducing their likelihood to seek service assistance.

- Limited knowledge or capacity of service providers and other professionals to recognize the issue or ask questions when screening for abuse which could help girls in reporting the issue. This is related to the dearth of specific guidance and tools available on the issue.

- Low awareness-raising and preventive efforts within the community and schools to inform youth, educators, community leaders and service providers of forced marriage and services for those at-risk.

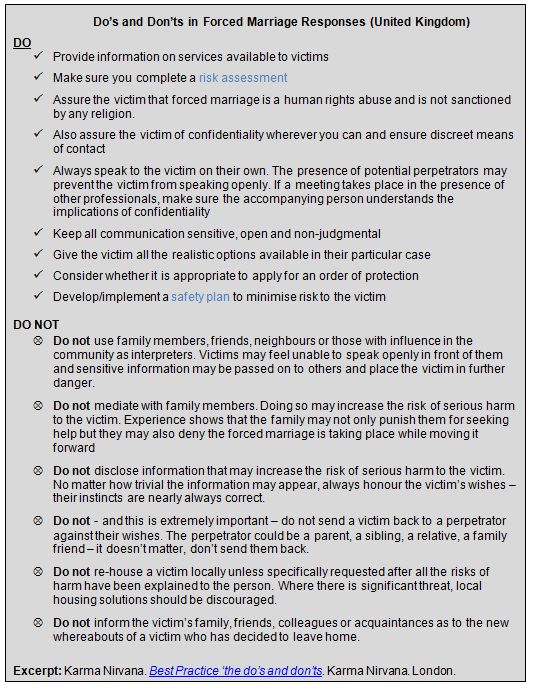

Shelter services for survivors or those at risk of forced marriage should consider their specific needs by:

- Including a definition of forced marriage in relevant policy documents and integrating the issue within agency practices, for example, during intake and risk assessment processes.

- Having policies that respond to women and girls’ perception that their need for shelter is damaging to their family honor; and the potential for family members to use coercive and threatening behaviour to compel their return or sever their contacts with support services.

- Ensuring anonymity of women and girls seeking support, particularly given the potential for retaliation and further harm by their family.

- Providing counseling and care that reflects understanding of the impact of sudden absence of family.

- Providing special protection measures for victims and shelter personnel to address the heightened risks associated with families that may pursue the victim. This may entail “intensive searches, extreme threats, emotional blackmail, promises and reporting them to the police or attempting to track down the escapee by smuggling female family members into the refuges” (TerNedden, Hamburg Ministry for Social and Family Affairs).

- Facilitating access to long-term accommodation that helps them transition into a life independent of their family. See, for example, the experiences of the Umoja village and the Tasaru Ntomonok Initiative in Kenya.

- Providing opportunities for girls to seek assistance who may not be able or ready to visit a shelter facility (Hamburg Ministry for Social and Family Affairs).

(Advocates for Human Rights, Rights of victims; Tahirih Justice Center, 2011; Roy, Ng, and Larasi, 2011)

Tool:

Tool:

Forced Marriage Unit website (Foreign and Commonwealth Office). This website features various resources for the general public, professionals from the security, health and social welfare sectors, advocates and girls at risk or victims of forced marriage. Examples of resources include: Forced Marriage Survivor’s Handbook; Forced marriage e-learning training; and the Multi-agency practice guidelines: Handling cases of Forced Marriage, which provides an overview of issues around forced marriage, good practices in keeping victims safe, and multi-agency guidelines in the areas of health, educational institutions, police, children's social care, adult social care and housing. The site is available in English.

“Honour”-related violence

Women and girls escaping “honour”-related violence may face some barriers similar to those at risk of forced marriage, although services for those at risk of ‘honour’ crimes should also consider the following:

- The availability of shelters is considered to be the most crucial aspect of assisting women escaping “honour”-related violence.

- Longer-term supports (financial, empowerment and security) for women are critical as relatives and others may pose threats to the victim and expose them to violence long after they have escaped the immediate threat to their safety.

- There may be more than one woman facing threats of violence in families of women escaping ‘honour-related violence’. Women escaping these situations should be assisted to keep contact with family members who do not pose a threat to her, or who may be at-risk themselves.

- Women may be at-risk of violence from multiple perpetrators, who may or may not be known to the woman, which requires caution when applying existing standardized risk assessments to assess the risk of women and girls escaping ‘honour-related violence’. These tools are limited in predicting lethality in such cases and can be ineffective. Ideally, risk assessements specific to “honour”-related violence should be used (Elden, 2007).

Tools:

CAADA-DASH MARAC Risk Identification Checklist for the identification of high risk cases of domestic abuse, stalking and ‘honour’-based violence (Coordinated Action Against Domestic Abuse- CAADA, 2012). This risk assessment checklist, developed through collaboration of various agencies as part of efforts to effectively implement the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference in the United Kingdom, aims to help frontline practitioners identify high risk cases of domestic abuse, stalking and “honour‟-based violence. The checklist comprises 24 yes/no questions that are completed in collaboration with the woman or girl seeking help and is complemented by guidance to assist practitioners facilitate appropriate safety planning. Available in English, Arabic, Bengali, Mandarin, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Romanian, Somali, Spanish, Turkish, Urdu, Vietnamese and Welsh.

Honour Related Violence: Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls in Patriarchal Societies (Kvinnoforum, 2005). This manual is for program designers and managers working on honour-related violence against women. The manual provides guidance to promote increased awareness and multi-sector collaboration on honour violence. The manual is organized into 11 sessions covering basic concepts of honour-related violence, empowerment, gender, patriarchy and power in violence, sociocultural contexts, among other issues; each session includes various exercises for improving knowledge, cooperation and actions related to addressing honour-related violence as well as a sample training agenda. Available in English.

Female Genital Mutilation

Similar to other harmful practices, girls escaping female genital mutilation have greater barriers to receiving services and few safe accommodation options. The young age in which female genital mutilation often takes place (usually affecting girls under 18) creates specific legal and operational challenges for shelters and other service providers receiving girls seeking support.

A specific challenge for shelters and services for girls at risk of female genital mutilation/cutting is the potential for organizations to be falsely accused of abduction or kidnapping. Shelters may not be able to legally accommodate girls without a legal guardian’s consent and social service agencies may not be able to provide state protection or assert authority over parental rights in such cases.

Girls fleeing female genital mutilation are likely to need longer-term accommodation supports, and will have fewer options to transition back into the community if they cannot safely return to their families. This may pose particular challenges in communities which only have limited, emergency shelter facilities or lack the capacity to meet the specific needs of girls.

Strategies for shelters to consider in developing services for girls at risk of female genital mutilation include:

- Accessing referrals and collaborating with from government authorities, which can help ensure girls are protected and allow service providers to legally shelter and support them (United Nations Population Fund. 2007).

- Creating partnerships with community leaders, educators and individual supporters to increase support available to girls outside their immediate family; provide an additional mechanism for monitoring the safety of girls who return to their families; and increase public dialogue and awareness on the practice and its harmful consequences to help shift tolerance and attitudes against it.

- Develop holistic programming, which includes provision of protection and support for girls at risk of abuse, but also training and economic opportunities for women who perform the practice, to create alternative livelihood options and incentives, which can help in the process of abandoning the practice.

Example: Tasaru Ntomonok Initiative: Safety Net for Girls Escaping Female Genital Cutting and Early Marriage (Kenya)

The Tasaru Ntomonok Initiative (TNI) is a community-based organization which operates within the Narok district in the Southern Rift Valley of Kenya. After years of community-based advocacy to change attitudes supporting female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and forced marriage, it established the Tasaru Rescue Centre in 2001 by providing a safe house to assist girls attempting to escape the practices. Through the Safety Net initiative, developed with financial support from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in 2003, the project continues to provide shelter support, while promoting longer-term solutions to these problems by reconciling girls with their families and communities, and using awareness raising strategies to discourage the practices of early marriage and FGM/C. The Initiative is sustained through private donations and has led to various achievements including:

- Over 2,000 girls supported by the Centre or reconciled with families have avoided child marriage and FGM/C (based on data from 1999-2007).

- Local authorities, community leaders and elders support and contribute to the initiative’s efforts, including in the identification of at-risk girls and in facilitating girls to leave a forced marriage.

- The District Education Committee has promoted the establishment of dormitories in all primary schools to protect girls aged 8 to 14, the period during which FGM/C and forced marriage often occur.

- Alternative rites of passage for adolescent girls are growing in the community.

- Support for women who perform FGM/C to develop alternative livelihood activities (such as becoming traditional birth attendants)

- Engagement and awareness-raising with a wide group of local stakeholders, including law enforcement, local administrators and religious leaders.

Background

In Maasai culture, genital cutting is an initiation into adulthood and is also considered a prerequisite for marriage which occurs, on average, by age 14. A 2009 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) showed that 73% of Maasai woman between 15 and 49 years old had undergone FGM/C (a decrease from the 93% of Masai women who reported having experienced FGM/C in the 2003 DHS). In addition to the health risks of female gential mutilation, including trauma, bleeding, difficult childbirth, and HIV infection, girls who undergo cutting are often forced into polygamous marriages. A 1990 study showed that as many as 80 per cent of girls who had experienced FGM/C dropped out of school due to forced marriage (UNFPA, 2007). Both practices are perpetuated by social attitudes and beliefs which include: unmarried women are social outcasts; genital cutting is the only way a girl can enter adulthood and prepare for marriage; and it is a bad omen to marry an uncircumcised girl, whose blood is considered ‘unclean’.

Implementation

The iniatitive was founded by two activists from the Maasai community using public education campaigns and advocacy with families to raise-awareness and change attitudes related to the practices. The Tasaru Centre was established in 2001 to expand the protection and advocacy efforts. Key components of the initiative include:

- Provision of shelter and support for girls fleeing either FGM/C or forced marriage. In 2007 alone, the Centre provided shelter to 68 girls.

- Development of a referral procedure through engagement with the local Department of Education and administration, which enable girls to leave forced marriages safely and receive protection from the state (either through accomodation at the Centre or if choosing to return to their families). This also facilitates their continued education and protection from either FGM/C or forced marriage.

- Organization of alternative rites of passage during August and December, the months during which FGM/C is usually conducted. These rituals involve older Maasai women as godmothers (which strengthens local ownership and sustainability of the practice), teach girls about important cultural beliefs and encourage discussion on sexual and reproductive health issues to educate the girls and provide information to help them make informed decisions as adults.

- Community awareness-raising and training to community members, teachers and authorities on the negative consequences of FGM/C, and education for adolescent girls on their rights and key sexual and reproductive health issues such as HIV.

Throughout its implementation, resistance to abandoning FGM/C has come from groups including:

- Boys, who associate the practice with finding a culturally-appropriate wife;

- Poverty-stricken parents, who view marriage of their daughter as a potential source of income.

- Women performing FGM/C, who rely on the practice for their livelihood.

- Politicians, who support the practices to avoid offending influential supporters and may feel threatened by the emergence of women leaders who challenge traditional practices.

Lessons Learned

- Eliminating harmful practices requires comprehensive approaches involving all stakeholders. While the Centre is focused on shelter protection and education support for at-risk girls, its community-based awareness-raising; promotion of alternative rites of passage and livelihood activities engaging women performing FGM/C, have been instrumental in reducing support for the practice.

- Effective networking and community collaboration is a key element to facilitate success, through the establishment of mechanisms for coordinating educational responses for female children among broader efforts to provide a safety net for girls; and improving monitoring of incidents through a community-based early warning system to identify girls at risk of circumcision and early marriage. This supports the implementation of the provisions of the Children’s Act and has resulted in greater harmonization of state and non-governmental efforts to safeguard girls and promote their rights.

- Framing advocacy in terms of benegits for individuals and communities is most effective for changing attitudes, as demonstrated by the communication with Maasai parents on the potential economic benefits of education for their daughters, which was a key element in parents' decisions to allow their daughters to attend school and make their own choices about when to marry.

- Early engagement with community members is essential to establish partnerhsips, obtain commitment and prevent misperceptions of programming. The history of community advocacy and campaigns that preceded the establishment of the Tasaru Centre demonstrates the importance of a phased and comprehensive approach to addressing FGM/C and forced marriage. This consultative approach also enabled the organizers to obtain consensus, influence change in perspectives on social norms and practices, and minimize the challenges and threats to the initiative.

- Men must be engaged as important allies for change. The threat of rescued girls being forced by male relatives to undergo FGM/C during school holidays (when many would visit their families) was addressed by targeted awareness-raising efforts with Maasai men.

- Physical protection for girls against FGM/C and forced marriage must be complemented by education and life skills. The Tasaru Centre does not only serve as a safe accommodation for girls, but provides critical education regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights, and changing behaviours that prevent risk of HIV infection and drug abuse, to strengthen their protective factors upon return to their families and communities.

Adapted from UNFPA. 2007. “Kenya: Creating a Safe Haven, and a Better Future, for Maasai Girls Escaping Violence.” Programming to Address Violence Against Women: Ten Case Studies. UNFPA. New York.