Women’s groups and community-based organizations can provide important bridges between security personnel and local communities. Establishing mechanisms for consultation and collaboration with these groups can help improve the response of police to violence against women, with specific contributions of community organizations including:

-

Providing the first response to survivors of violence (e.g. immediate social support, protection, shelter, basic medical assistance and trauma counselling), and subsequently assisting women to contact police or accompanying them to the local police station. These organizations may refer women and girls onto other support services or continue to actively support them through the process of seeking justice and redress – including through the provision of legal assistance. In cases where women leave their home and community, it is usually civil society organizations that support the reintegration of survivors back into their communities or new settings.

-

Contributing critical local intelligence on criminal activity, the type and location of the security risks specifically affecting women and girls.

-

Sharing information to communities on the role of uniformed personnel in preventing violence and supporting survivors, which is particularly important in situations where trust in the police is low following a period of conflict, neglect or abusive police action.

-

Acting in a vital oversight role in holding the police to account for their performance in violence prevention and response, and ensuring any abuses perpetrated by security personnel are addressed. Often women’s organizations are well-networked and can help provide vital links between communities and advocacy groups at the regional and national levels.

-

Strengthening police knowledge and capacity to address gender-based violence (for example, by facilitating the development of and/or conducting gender training for police and military personnel).

-

Facilitating local ownership and community awareness of police initiatives and raising police awareness of the referral network and other opportunities for partnership with communities.

-

Advocating and assisting with efforts to increase female representation and gender mainstreaming within security institutions.

Different approaches and specific mechanisms that can be established to improve engagement and dialogue between the police and community organizations and actors include (Barnes and Albrecht, 2008):

-

Establish local community security or violence against women committees, which include representatives of different sectors of the community, including women’s organizations, as well as the police – and have a specific mandate to reduce violence against women and girls. Such committees can serve as important fora to share information and views on how to improve community safety, for example by undertaking an assessment of security and safety within the community; raising awareness and providing training (e.g. police training informal security patrols in how to respond to incidents of violence); and local actors raising police awareness and knowledge of local customs.

Examples of local security committees and citizen security plans

In Peru, the parliament created a National Citizen Security System to promote local participatory crime prevention initiatives and make police more responsive to communities. This system relies on local-level institutions, with the establishment of Local Citizen Security Councils (Consejos Distritales de Seguridad Ciudadana). In the Councils, local police commanders work with authorities and community representatives on crime prevention. The Councils are bottom-up mechanisms to hold police accountable for their conduct and quality of service and offer an important opening for community participation in security issues. They are mandated to design a citizen security plan at the municipal level based on an assessment of local safety and security issues. The security plan is implemented by mobilizing local cooperation and resources. Councils are also in charge of evaluating the plan’s impact and monitoring the performance of public employees implementing the plan, including police.

Similar bodies, such as Local Security Councils (Consejos de Seguridad) have been established in Chile, Colombia and Guatemala. In Colombia, members of the Local Council have included the local police and military chiefs, the mayor and academic and private sector representatives (Barnes, K. and Albrecht, P., (2008), ‘Civil Society Oversight of the Security Sector and Gender – Tool 9’, Gender & Security Sector Reform Toolkit, Geneva: DCAF, OSCE/ODIHR, UN-INSTRAW).

In Haiti, a DFID-funded UN Women programme has been working in 9 communities to promote women’s involvement in community-level initiatives to address violence against women and to improve community security. In each community, the programme has supported women’s organizations to establish local comités de sécurité. These committees include representatives from all sectors including local government, police, judiciary, education, health, the church, the voodoo community and women’s organizations. Their role is to discuss women’s security needs, raise awareness about violence against them and improve the responsiveness and accountability of local service providers (including police) as part of a community-level referral network. Initial results suggest that these committees play an important role in increasing confidence in the police with respect to incidences of violence (Spraos, H. 2011; McLean Hilker, L. 2009).

Vanuatu Women’s Centre has established Committees Against Violence against Women, which play a pivotal role in promoting community awareness and advocacy to address the issue, and supporting women in rural areas. The committees comprise prominent men and women from the community—in some cases elders, chiefs and rural practice nurses and also coordinate with the police and judiciary. The committees receive training from the Vanuatu Women’s Centre in legal literacy and basic counselling skills. There is evidence that the committees are increasing community awareness of violence against women, with an increase in media reporting on the issue and more cases of gender-based crimes being taken to traditional and formal courts for prosecution (AusAid (2008); AusAid website; AusAid (2009) Vanuatu Country Report).

-

Establish Community Police Forums: Community police forums or boards are formal coordination structures which attempt to build bottom up accountability and allow community members – especially women and girls – to monitor police responses, provide feedback and propose changes. The boards can help to improve police-civilian relationships, encourage reporting, as well as serve as a formal recourse mechanism for individuals and communities to register complaints and concerns. Although there is only limited experience integrating a mandate on violence against women and girls into these fora, emerging lessons include:

-

The representation of women in any oversight mechanism is essential, especially women’s advocates and representatives of organizations supporting survivors.

-

Capacity development of board members and civil society organizations to provide effective police oversight must include guidance for conducting oversight on violence against women.

-

Joint police and civilian oversight body training can increase collaboration and mutual respect and is an essential part of establishing clear procedures for incident reporting and response.

-

Examples of Community Police Forums

Bangladesh: Community Police Fora emerged out of a situation of increasing violence in Bangladesh, where trust between communities and police was weak. The Fora have a leadership role facilitating activities that are jointly identified by community members and police, and have gradually evolved as independent mechanisms that can sustain their operations with minimal external support. A Forum includes 20 - 25 members, whose activities are led by a sub-district level elected representative, or by the district superintendent of police. Other members include police officers, Ansars (government-funded security officers of lower rank than police), and representatives of a facilitating NGO, with school principals and teachers, business persons, religious leaders, representatives of women’s organizations, farmers, and other community members. Each Forum meets at least once per month and more frequently if urgent issues arise. Meetings focus on the present public security environment, particular issues or opportunities to which the Forum can respond, review of its activities, and plans for new programme initiatives. Several Fora have established sub-committees for different security issues which offer the potential to address community concerns related to violence against women (Asia Foundation, 2009).

Sri Lanka: Following a 2009 survey conducted in Kandy District which showed that the Sinhalese, Tamil, and Muslim communities were interested in working with the police on common issues of concern, the Inspector General of Police indicated the need for the police force to become a more professional and “people-friendly” service, and noted interest in scaling up community policing country-wide to establish an ethos of public service and accountability toward community members, regardless of gender or ethnicity. The police service has since joined citizens at community-led forums to better understand crime incidents and conflict issues. For example, in Gampola, most cases discussed at a forum surrounded domestic violence, land disputes, alcoholism, physical assault, and property damage. Given that both women and men felt comfortable to discuss the frequent – but highly taboo – cases of alcoholism and domestic violence, it was clear that the community found the forum to be a safe place to voice their opinions. Some people voiced concerns over the widespread illegal brewing and marketing of alcohol in homes, which was attributed to contributing to numerous incidents of domestic violence. After listening to these concerns, the Gampola police identified illegal brewing as a policing priority that could be included in future public awareness campaigns against alcoholism. Community representatives confirmed that the monthly forum was very helpful for discussing issues of domestic violence, while agreeing that the problems did not have easy solutions (Levy, 2010).

South Africa: The local government and the South African Police Force participate in and collaborate with Community Police Forums to set joint priorities and objectives on crime prevention. The Forums involve civil society organizations in formulating local policing priorities and crime prevention initiatives, using community security plans, which identify:

-

programmes, projects or actions that the Community Police Forum will implement;

-

where the Forum will get funds for the projects; and

-

how the project will promote the aims of the Forum.

The community security plan is based on a community safety audit that helps to:

-

focus on the most serious problems when there are limited resources;

-

give people facts when they disagree about the most serious problems; and

-

coordinate the work of different organizations to prevent duplication.

A community safety audit is carried out through a five step process to identify:

-

The crime problems in the community (e.g. domestic violence).

-

Which organizations are doing what: Some organizations may already have crime prevention projects, and there may already be activities to prevent domestic violence and support those affected directly and indirectly.

-

The physical and social characteristics of the area: To understand the causes of crime in a community, the physical and social characteristics of the area must be known. For example: women are more at risk of domestic violence and sexual assault; young men are more at risk of other violent crime and also most likely to commit crime.

-

The problems which are most pertinent to women, which can be a result of actual violations or a perceived threat (e.g. if violence is perpetrated against one woman in a public area, a majority of women in that area will perceive insecurity).

-

Details of the most important safety issues that women and girls face in their community, which will vary given each area’s social, economic, legal, cultural and political context.

See Additional guidance on safety audits in the Safe Cities module.

Promising Practice: Local guards develop protocol for responding to violence against women (Rosario, Argentina)

The Municipal Urban Guard (Guarda Urbana Municipal) in Rosario (Argentina) is an unarmed community police force established in 2004 comprising young men and women which collaborates with community members and local authorities to promote safety in public spaces such as parks, streets and recreation areas. In 2008, the Guard, local authorities, women’s and social affairs representatives and survivor support groups jointly developed a protocol for responding to women survivors of violence, based on the lessons of local police and authorities from Fuenlabrada, Spain, who had developed a similar community protocol. Read the full case study on the Municipal Urban Guard’s experience.

Manual de Capacitación para la Guardia Urbana Municipal (Training Manual for the Municipal Urban Guard) (CISCSA - Women and Habitat Network, 2008). This resource on community policing from Argentina is the result of several trainings for local police on violence against women in cities. It comprises four modules: 1) Urban Violence and Violence against Women; 2) Deconstructing Myths and Beliefs regarding Violence against Women in the City; 3) International Conventions, National and Provincial Laws; and 4) Recommendations and Necessary Actions; and is accompanied by a glossary of terms and an appendix of institutional and social resources for responding to violence against women in Rosario. In addition to the theoretical guidance, each module contains practical exercises for reflection and analysis to be used to evaluate the training. Available in Spanish.

-

Institute regular meetings between community leaders – elected and traditional – and the police: In many contexts, survivors of violence and families may be encouraged or have a tendency to first approach traditional or elected community leaders to mediate or intervene in cases of domestic and sexual violence. Police engagement with traditional leaders is essential to promote the human rights of women and girls in these processes and to ensure survivors have the opportunity to report cases to the police and receive other appropriate referrals in accordance with the law.

-

Conduct outreach and communications activities with communities, especially men and boys: Both the police and local organizations can conduct important outreach activities with communities, especially men and boys, to raise awareness of human rights and gender equality issues and promote discussions on gender-based violence prevention and response. These activities can increase trust in the police, and should also ensure that community members and organizations are aware of the responsibilities of security personnel with respect to the issue. Key priorities for communications and awareness-raising by the police include:

-

Awareness-raising activities on the relevant laws and policies in place;

-

Local campaigns with civil society actors on different forms of violence (e.g. domestic violence, trafficking, sexual assault/ rape, sexual harassment in public spaces);

-

Information on the reason and process for reporting incidents of violence to the police (why, where and how) and on the operation of the local referral pathway;

-

Specific school activities on violence prevention in collaboration with the ministry of education;

-

Translation of all police and military protocols and procedures into relevant languages and posting at all police stations in prominent places, accompanied by a communication and training plan;

-

Posting procedures that relate to interactions with the community in places with high visibility and levels of police-public interactions (parks, plazas, markets, etc) and accompanied by a public information campaign.

-

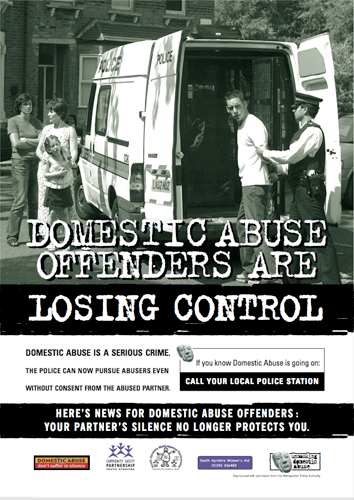

Examples of awareness-raising materials about the role of the police

Source: Raising Voices.Preventing Violence against Women Communica tion Materials .

Source: Raising Voices.Preventing Violence against Women Communica tion Materials .

Source: South Ayrshire Multi-Agency Partnership

to prevent Violen ce against Women.

Source: Dorset Police. 2009. Party Season Rape Awareness Posters – Gwent, Dorset, Greater Manchester (United Kingdom).

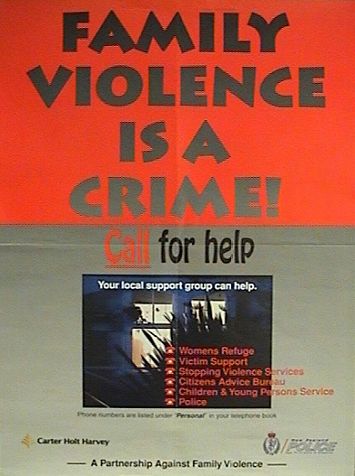

Promising Practice: New Zealand Police Family Violence Campaign

- Encourage reporting or help-seeking by women and children experiencing violence- and by others witnessing abuse.

- Deter offenders and potential offenders from engaging in or continuing abusive behaviour, and encourage them to enroll in men’s behaviour change groups.

- Improve police enforcement of the laws related to domestic violence.

In addition to the central campaign message “family violence is a crime – call for help,” specific messages were developed for key groups, such as the police (family violence situations at home can result in serious outcomes that would be treated very seriously in any other context- such as murder). The approaches used by campaign included:

-

Mass media: 3 documentaries on primetime national television; 2 television commercials series (14 ads total); 2 music videos; print advertisements; posters; signs at sporting venues and on buses.

-

Community interventions that engaged both police and non-governmental agencies, including in the establishment of the toll-free helpline (0800) in conjunction with the airing of the documentaries.

Community interventions that engaged both police and non-governmental agencies, including in the establishment of the toll-free helpline (0800) in conjunction with the airing of the documentaries. -

Capacity development and institutional efforts to challenge police force attitudes on the issue, including briefings, internal publications, policy changes (e.g. authorizing police to make arrests without needing women to press charges) and training.

An evaluation of the campaign revelaed key areas of change:

-

There was a very high level of awareness of the campaign (92% by late 1995), and two-thirds who recalled the campaign said it influenced their attitudes on family violence.

-

Thousands of calls were made to the helpline, mostly from survivors, but also including witnesses (28% from the helpline set-up after the first documentary). Approximately half of callers reported it was their first disclosure of the violence.

-

Women’s services reported a significant increase in women’s help-seeking.

-

There was a 44% increase in police records of men’s assaults on women from 1993 to 1994, with the number of offences dropping slightly in both 1995 and 1996.

-

Prosecutions for family violence more than doubled from before to after the campaign.

-

There was a 50% increase in self-referrals from men seeking help on family violence problems, and referrals from judges in the courts doubled. Men comprised 27% of callers to the helpline after the 2nd documentary.

- In the 6 years prior to the campaign, an average of 14 women were murdered a year by male partners. This dropped to 10 in the first year, 9 in the second, and 7 by 1996.