Trafficking victims face special circumstances. For example, unlike domestic violence victims who may be escaping a single perpetrator, trafficking victims may be escaping an entire network of organized crime. They may be particularly vulnerable due displacement and a lack of resources needed to implement solutions and escape their situation; limited knowledge of the criminal justice system; extreme isolation; and intense trauma and mental health needs. International trafficking victims may not have citizenship in the country they are residing in, creating additional challenges in assisting them (Clawson, et. al., 2003).

Shelter services for women and girls who have been trafficked must work closely with multiple systems (e.g. government departments and institutional services related to counter-trafficking, victim assistance and protection frameworks) at the local, national and in some cases, international level to address their complex needs (International Organization for Migration, 2007).

Within these systems, shelters can contribute to the identification of survivors and enable women seeking assistance through the coordinated referral systems to understand their rights and support them to make decisions throughout the process.

Considerations in providing advocacy and improving coordinated responses for trafficking survivors, include:

- Reliable victim identification requires institutionalized cooperation between social services, NGOs including shelters and law enforcement agencies. Given the severe consequences of retaliation by traffickers, among other barriers, women may often be reluctant to disclose information or talk about their experiences with abuse and trafficking, making it difficult to identify their needs. The woman-centered principles and practices of women's organizations and shelters helps to identify women through building trust and credibility with victims, while the involvement of institutional and government services is important at this early stage for victim identification, and in providing information regarding residency options to them.

- The identification process can take time. As women are supported and begin to feel safe, the details of her story are often shared increasingly.

- Women may often be trafficked out of their communities and in many cases, across national borders. Shelters should plan for women who may require assistance with returning to their country of origin, reintegrating in their country or origin, or integrating into a destination country. The identification process should involve providing options to women, including the possibility of remaining in a host country, where she has been trafficked. For women trafficked across national borders, a reflection period is provided for in law. A reflection period gives victims of trafficking time for reflection and recovery during which they are eligible to receive services and benefits regardless of their immigration or other status, or their ability or willingness to cooperate with law enforcement and prosecutors. See “Reflection Period” in the Legislation module for more.

- Women should be provided with access to a range of services during the reflection period, including secure shelter or housing, clothing, health care and psychological support, professional advice, including legal advice, provided in a language that she understands and is comfortable with.

- Shelters should communicate and advocate within systems for responses that effectively address the overall residency and reflection needs of women victims of trafficking. For example:

- Ensuring an adequate reflection period for women victims of trafficking is needed (a minimum of 3 months and preferably 6 months) given the effects of control and abuse inherent in forced sex environments. During the reflection period, women should be entitled to access training and education, and uphold a legal work permit.

- Shelters should provide women with predictable information, making sure that she knows what will happen to her next, and including the possibility to return and remain in the host country/ community. This information should be provided and repeated continuously to support women to be clear about their options. Residence permits and assurances about the future is often important for legal cases to be successful.

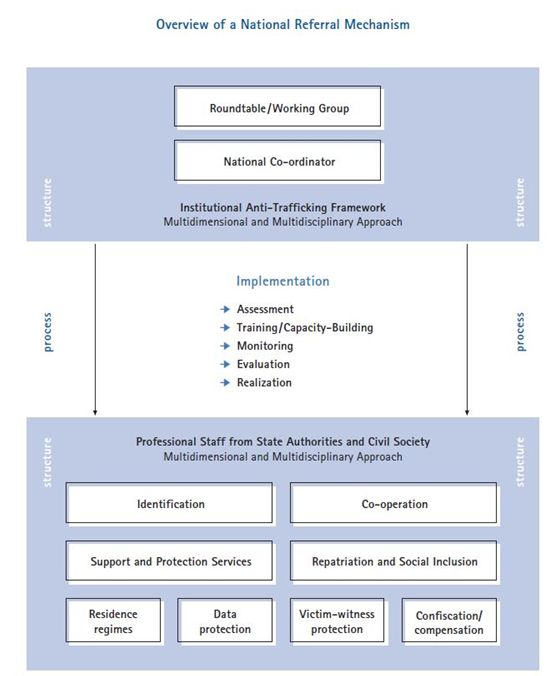

In addition to coordinated responses, shelters may participate in a national referral mechanism, which is a co-operative framework through which state actors fulfil their obligations to protect and promote the human rights of trafficked persons, co-ordinating their efforts in a strategic partnership with civil society (OSCE, 2004). While the structure of national referral mechanisms vary across countries and regions, an NRM should incorporate:

- Guidance on how to identify and respond to trafficked persons while respecting their rights and giving them power over decisions that affect their lives.

- A system to refer trafficked persons to specialized services such as shelters for protection from physical and psychological harm, as well as support services including medical, social, and psychological support; legal services; and assistance in acquiring identification documents, as well as the facilitation of voluntary repatriation or resettlement.

- Establishing appropriate, officially binding mechanisms that harmonize victim assistance services and processes with criminal investigation and prosecution efforts.

- A framework of multi-system participation that promotes an appropriate response to the complex issues surrounding trafficking and facilitates monitoring and evaluation.

NRM's are founded on ten principles of practice, in which shelters are part of a protection mechanism among a range of different specialized services, addressing the specific needs of each individual (OSCE, 2004). Considerations for shelters contributing within these mechanisms include:

- Acknowledging that women who are trafficked are victims rather than criminals in a basic element of respect for human dignity that can be afforded to them through providing access to accommodation and specialized services.

- Recognizing their role as the single centralized shelter within the NRM, allowing for the accommodation and support of presumed trafficked persons as well as providing a location for police to carry out their questioning. Medical and psychological care may also be provided in this location, which means that women may not be able to retreat into a private sphere and are not able to leave the protected accommodation due to security concerns or restrictions on their movement related to their status in the destination country.

- Understanding that trafficked women and girls have differing experiences and needs, based on their unique backgrounds and which influences their security and support needs (e.g. counseling and services). For example, some women and girls may not require protected accommodation since they already have a residence. Psychological and medical services should be provided in a flexible manner that allows victims to access them on a voluntary basis whether they reside in shelter or other accommodation in the community.

- Three components of specialized services are provided for within the NRM framework. These components are shelter, financial assistance and specialized services (including counseling, health care, psychological assistance, legal assistance, education or vocational training, employment assistance and support in dealing with authorities). Financial assistance and specialized services may be provided by shelter services as well as by other community-based services.

Example: Women’s Safety and Security Initiative (Kosovo)

Through the Women’s Safety and Security Initiative (WSSI) in Kosovo, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has worked to increase the capacity of public institutions to address trafficking and other forms of violence, and strengthen civil society capacity to monitor and advocate for accountability. The initiative aims to support the development of effective judicial and policing institutions; mechanisms for the implementation of government objectives related to trafficking; civil society engagement, assessment and monitoring capacities; and improved assistance to survivors of violence, specifically through its support to shelters.

Background

Violence against women is one of the most widespread human rights abuses in Kosovo, and continues to be regarded as a private matter, with women who report violence at risk of being displaced from their homes, losing custody of their children, and facing retaliation from perpetrators. While awareness of domestic violence issues has increased in recent years, underreporting continues. A recent survey conducted in Kosovo noted that 46.4% of women respondents experienced violence in their own homes, and more than half of survivors interviewed for a 2007 report did not inform police about their most recent incident (Farnsworth & UNFPA, 2008). Similarly, trafficking in Kosovo is recognized as a growing problem (particularly affecting ethnic Albanian women and girls from rural areas), although the extent of the issue is difficult to determine. For example, the International Organization for Migration reported 64% of victims assisted in 2005 were internally trafficked, with a third trafficked across borders into Macedonia, Albania and Italy. Poor investigation processes, including lack of adequate witness protection, are coupled with weak prosecution for traffickers due to misconceptions, lack of training (where prosecutors request victims testify in the presence of their traffickers, despite legal regulations against this); and collusion with traffickers.

Within this context, services for survivors are very limited and particularly difficult for women from minority communities to access (e.g. Roma, Ashkhali, or Egyptians). Lack of long-term assistance for survivors of all forms of violence is a key obstacle, forcing many domestic violence survivors to return to violent homes. According to a 2006 study of Kosovo Gender Studies Centre, 60-70% of safe house residents return to their spouses due to a lack of financial independence, and 90% of residents are unable to secure employment after leaving the safe houses. Trafficking survivors face equally limited support, with services often short-term and shelters challenged by the rise of internal trafficking and increasing demand for accommodation.

Approach of the Initiative

Recognizing the importance of multi-sectoral actors in prevention and response services, the iniatitive works in direct cooperation with a variety of partners across the justice, security, social welfare, and health sectors, such as:

- The Agency for Gender Equality (Office of Prime-Minister)

Public institutions and line ministries with relevant responsibilities including: the Ministries of Justice and Health; the Kosovo Police (Domestic Violence Unit and Trafficking in Human Beings Investigations Section); and the Department for Social Welfare, which has established minimum professional standards.

- Civil society, including non-governmental shelters; organizations which provide free psychological and gynecological, legal assistance and representation to women; and advocacy groups such as the Council for Defence of Human Rights and Freedoms and Kosovo Women’s Network

- International counterparts

Among activities related to establishing a strong legal and policy framework and strengthening institutional capacities, the initiative has invested in shelters, rehabilitation and access to justice for survivors. Specifically, five shelters for women and girls in the Prishtina/Pristina, Mitrovica, Peja/Pec, Prizren, Gjakova/Gjakovica and Gjilan/Gnjilane municipalities received grants to support year-long programming, which included medical, psychosocial—counseling, psycho-drama, education, daily vocational trainings and occupational therapies, in addition to infrastructure/equipment (e.g. security systems, beds, blankets, wardrobes, generators, computers, and printers). Forty staff from four shelters also received intense training on professional development, organizational and emotional management, and conflict resolution. Community members and local authorities were also engaged through the process, contributing to women’s economic empowerment. For example, 11 women were assisted to secure employment and post-shelter transition from the Gjilan shelter.

Results and lessons learned

An estimated 441 women were supported by the shelters between July 2009 and July 2010.

Other outcomes of the initiative included:

- Positioning violence and trafficking at the centre of the security sector reform agenda with ongoing advocacy and training of civil society and awareness-raising within society to change public perception of the issues (Muca, 2008).

- Successfully lobbying for the creation of a financial code for shelters through relevant line ministries (e.g ministries of health and justice) contributing to annual shelter budgets.

- Establishing a legal and policy framework for addressing the issues (e.g. development of the Anti-Trafficking Secretariat within the Ministry of Internal Affairs) and strengthened political will within key institutions (e.g. National Anti-Trafficking Coordinator and municipality engagement).

- Increasing the capacity and sustainability of shelters and other service providers to include efforts to ensure long-term post-shelter support for trafficking survivors (e.g. Rehabilitation Centre), and increase the capacity of safe houses for multi-ethnic survivors (providing staff trainings on cultural competency, standard operating procedures and related issues).

Lessons learned

- Inititives must be able to adapt their deliverable schedules to respond to changing political contexts and the non-linear dynamics of institutional change and priorities. This can ensure local ownership of interventions and increase the likelihood that practices and services will be institutionalized beyond the project timeframe.

- Coordination and efforts to address violence must be responsive to to local needs, priorities, and knowledge. Institutionalizing mechanisms for addressing gender inequality and violence against women within state institutions is a long-term process that requires sustainable programming. Cross-border issues (i.e. trafficking) require an additional level of cooperation with regional actors. Increasing women’s access to justice and security through strengthening state capacities must be complemented by efforts to empower grassroots actors to hold to account public institutions (e.g. by supporting civil society to monitor and report on the results of the judiciary, courts and prosecutors). This may involve building the monitoring capacities of local women’s and human rights groups and journalists. Issuing gender equality guidelines and training media to raise awareness of their responsibilities in promoting non-stereotypical images and educating people more broadly about the causes and effects of violence against women are also important.

- Training municipal offices responsible for gender issues in lobbying/advocacy, fundraising and networking with other local actors can improve coordination as well as institutional capacities.

Future efforts will expand existing supports and further engage the Ministry of Economy and Finance to ensure the economic sustainability of institutional capacities in certain aspects of the project.

Sources: Farnsworth, N. for Kosovo Women’s Network & UNFPA. 2008. Exploratory Research on the Extent of Gender-Based Violence in Kosova and Impact on Women’s Reproductive Health; Farnsworth for Women’s Network. 2008. Security Begins At Home: Research to Inform the First National Strategy and Action Plan on Domestic Violence; Muca, M. (NACSS), WSSI Mid-Term Evaluation 2008; UNDP Kosovo, Justice and Security Programme 2009-11.